(From Vol. XXIII, No. 4 of Art and Archaeology)

Treasure at the bottom of the sea or at the bottom of adeep lake is erne of the fascinating subjects which writersof romance and mystery tales make much of. ProfessorMesser of the department of Latin at Dartmouth has madean interesting investigation and study into the fate of twoRoman imperial pleasure barges sunk in Lake Nemi inItaly. Some of his material has formed the basis for countless newspaper and periodical stories on this subject. Itis a rule of the Alumni Magazine never to reprint articlesfrom other magazines, but in this case the investigation isof such enormous interest and the subject is such a fascinating one that the editors have agreed to break this rulefor once, and it is through the kindness of the magazineArt and Archaeology that the Magazine is permitted toreprint a portion of Professor Messer's story. It is understood that Lake Nemi is at the present time being drained,a huge piece of work, in order to find these two bargeslaunched by the Roman Emperor Caligula between A.D. 37and J/.1 and with them the priceless objects whichthey contain.

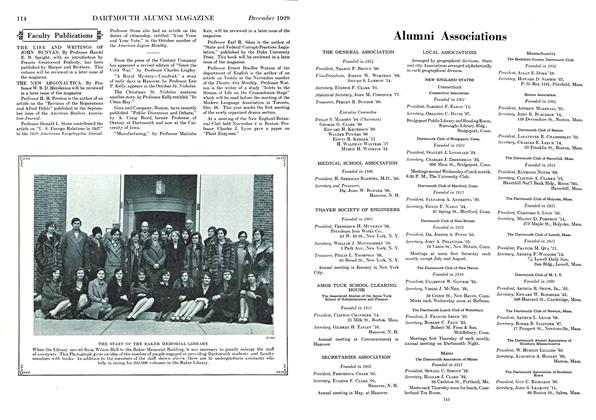

THE waters of Italy too, have surrendered their treasures of ancient art. But the perennial enigma and the perennial lure are the two imperial barges—houseboats, perhaps we should call themwhich are known to rest on the bottom of Lake Nemi. This lake nestles one thousand feet up in the Alban Hills in the crater of an extinct volcano near the site of Alba Longa, from which Rome, according to tradition, drew her origin, not an hour's ride from the Campidoglio. Nemi is a beautiful lake and profoundly poetic: the inspiration and the despair of the many artists who attempt yearly to record its charm on canvas. The lofty banks give the waters a dark tinge and the wild country about adds an air of mystery. L'occhio di cuposmeraldo, "the eye of dark emerald," the Italians call it. One feels that its depths hide secrets.

On the north shore Diana had her most famous temple and grove (nemus, from which the modern Nemi is derived) and the lake was known to the ancients as "Diana's Mirror" from the clear reflections on its surface. The worship of the goddess here was as strange and mysterious as the country in which the sacred enclosure stood. The rex nemorensis, the high priest of the goddess, must be a runaway slave, one who had come to the shrine and secured his pontificate by killing his predecessor in mortal combat—

The priest who slew the slayerAnd must himself be slain.

A region of such enchantment as these Alban Hills became popular with the Romans of the late Republic and of the Empire as a site for magnificent villas. Here Cicero had a place of retirement, and Lucullus—famed alike for his cruelty and for his luxury—here sought refuge from the noise and heat of Rome. Here the Emperors built great establishments of rest and pleasure and, if we may believe the ancient chroniclers, of revelry as well. Suetonius connects Caligula with the lake in one of his unforgettable anecdotes of the mad Emperor. Thinking that the priest of Diana's shrine had held office long enough, he hired a great butcher of a slave to go and slaughter him.

On the surface of Nemi, then, some time between A. D. 37 and 41 Caligula launched the two great ships which now lie at the bottom. They are sunk near the sacred enclosure of Diana, one fairly near the shore, the other farther out. The latter seems not so richly adorned and was perhaps auxiliary to the first. The existence of this second ship was not discovered till 1895, which explains why the references in what follows are to a single ship: investigation has not yet seriously concerned itself with this later find.

Quite unlike the case with regard to the ships of Anticythera and Mahdia, a tradition of a vessel of fabulous magnificence sunk in Lake Nemi had persisted from imperial times and was never wholly forgotten. Peasants fished over the spot for centuries and no one knows what prizes have been secretly recovered and sold! The Renaissance, however, first conceived the idea of salvaging the barge entire. In 1436 Cardinal Prospero Colonna, who owned Lake Nemi, called to his assistance Leon Battista Alberti, famous as a geometrician as well as an architect. Alberti built a monster raft supported on empty casks. He placed powerful windlasses aboard and summoned divers from Genoa to fasten grappling hooks to the hull of the submerged boat.

The performance was to be an impressive one. When the preparations were completed, the Cardinal invited all the great personages of the Papal City, clerical and lay, to watch the ship rise spectacularly from the water. In this august presence the supreme effort was made. The winches turned and the cables groaned, but the ship did not rise. All that was accomplished was to tear off part of the prow and sides of the vessel. Bits of wood, bronze, and lead were brought to the surface. The systematic destruction of the ship had begun.

A century later, in 1535, Francesco de Marchi made the second important attempt. He availed himself of the invention of one Guglielmo di Loreno, which, to judge from the description, must have been a sort of diving-bell or diving-dress—perhaps the earliest use of this apparatus. In this de Marchi himself descended. He complains in his account that he could not remain down long and if he lost his footing he would be drowned by the water's entering the contraption. He declares that he saw rooms in the palace which he believed built on the deck of the boat, but neither he nor di Loreno dared enter on account of the risk of becoming entangled and drowning. This time, also, hawsers were attached and an attempt made to raise the ship. De Marchi succeeded in ripping off enough wood "to load two fine mules," a section of floor and various objects of bronze adding to the damage done by Cardinal Colonna. For three centuries the ship had rest from any systematic destruction. But the cupidity of the fishermen of Nemi had been aroused and they never ceased trying with hook, rope, and grapling iron to strip from the buried mass some booty—a nail, a plate of bronze or lead—for which they found a ready market. Then came a third major attempt made in 1827 by Annessio Fusconi. He, too, had a special diving-dress of his own invention, a raft of original construction, and novel and powerful hoisting machinery. He also succeeded in recovering some smaller objects and more fragments of wood. But his cables snapped at the weight of the wreck and as heavy rains cooled the waters of the lake operations had to be suspended. During this suspension robbers carried away everything, apparatus and all!

The last great violence was begun in 1895 with all the appliances of modern science, and when, strangely enough, the minister of public instruction was Guido Baccelli, a name famous for service to Roman archaeology. Eliseo Borghi concluded an agreement with the Orsini family, who had jurisdiction over that part of the lake, and secured the consent of the government to his attempt. He sent down divers in modern diving-suits who brought up the beautiful bronze objects which form so effective a display in the Museo delle Terme today. The work of destruction went on during the summer of 1895 until the united protest of intelligent people showed the government its error and the operations were stopped. From then till now the authorities have forbidden any further attempt to recover the ships or objects from them.

With this year of grace 1927, a year of intensified national feeling in Italy and consequently of heightened interest in archaeological research, the subject of salvaging the ships has come up anew. The government has decided to solve the problem of how to recover the imperial barges provided the cost is not prohibitive. A commission of investigation has been appointed and at least one definite principle has already been established: no program will be adopted which will in any way further endanger these precious documents of Roman civilization.

Suggestions have been invited from all sources, and France, Spain, Belgium, and Holland have proposed schemes, in addition to the countless plans originating in Italy. These plans the commission is now engaged in sifting. They divide themselves roughly into two classes: (1) projects for raising the ships and (2) projects for lowering the surface of the lake. Those who favor the first method cite the raising of the Leonardo da Vinci and other imposing works of salvage which have been accomplished in the case of monster vessels, especially since the war. They forget that the broad ways of ocean afford an easier access for powerful machinery than the road over the crater edge of a mountain. Furthermore, the barges lie on a slant toward the center of the lake, and hence have become filled with mud and roots. Their timbers have rotted from the action of the water and it seems well-nigh impossible to raise them without rending them to pieces. The lake floor, furthermore, is covered with a deep stratum of slimy mud above which floats suspended a film of gossamer-like particles which on the diver's slightest move rise in clouds and obscure objects even close at hand.

So the commission at present inclines to the second means, the draining, total or partial, of the lake and the removing of the ships as if they were stranded in a meadow. In this way not only the ships would be recovered but also the myriads of small objects which have fallen from them or which have been torn off by their tormentors. When the commission has studied the suggested plans through experts it will be possible to see whether the cost of execution will be prohibitive.

An archaeologist immediately thinks of the functioning of the ancient emissarium of Nemi. But this has been found impossible due to the damaged condition of the Roman outlet. The Alban Lake, however, still has its Roman emissary functioning perfectly today, though built at least as early as 397 B.C. As this lake is eighty- five feet lower it may be possible, by transferring the waters of Nemi to it, to use this ancient wonder of Roman engineering for restoring to the modern world Roman imperial barges. One must, however, leave ways and means for the present to the commission.

Meanwhile one may speculate as to the nature of the ship which has been up to the present the object of study. Till 1895 it was called the barge of Tiberius, but in that year the recovery of inscribed lead pipe points conclusively to Caligula. Suetonius tells the story of Caligula's extravagances with great gusto: he invented new types of baths, and banquets with bizarre foods; he drank pearls of great price dissolved in vinegar; he laid out villas with entire contempt of cost, desiring nothing so much as to do that which men declared impossible; he built Liburnian galleys with ten banks of oars, their sterns set with precious stones, with sails of varied hue, with great bathing establishments on them and with porticoes and banquet halls. In these, says Suetonius, he was accustomed to coast along the shores of Campania. It has been suggested that Suetonius has suffered some confusion and that his description is rather that of the ships of Nemi. The theory is at least plausible.

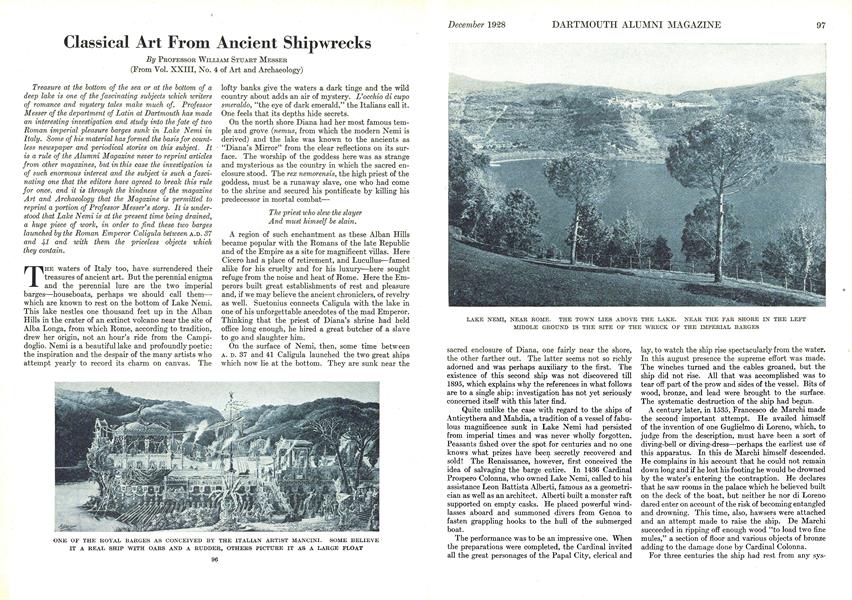

What was the nature of the imperial vessel? The Italian naval engineer, Malfatti, who interrogated the divers of 1895 on behalf of the ministry of public instruction, is convinced that the vessel was a real ship with rudder and oars and capable of navigation. Others are disinclined to believe this and hold, with the earlier investigator, de Marchi, that it was rather a great float with elaborate superstructures,' a palace, gardens, chapels, adorned with marbles, bronzes, precious stones and all the luxuries which the mad emperor knew so well how to employ. For similar floating villas Dr. Corrado Ricci, chairman of the investigating commission, cites the ships of Hiero 11, tyrant of Syracuse, of Cleopatra, of Borso d' Este on the Po, of Ludovico Gonzaga on the Mincio and the Signoria of Venice on the Grand Canal. The answer to the questions awaits the report of the commission and the funds necessary to carry out the accepted plan.

The objects which have already come to light give indication of the significant facts on Roman life and art which we may expect from complete recovery of the vessels. There are some bronze pieces in the Vatican collections and a ship's beam in the Museo Kircheriano; and one shudders at the thought of how many treasures may have been secretly dispersed. But the most im- portant known recoveries are those now on view in the Museo delle Terme in Rome, brought to the surface early in the effort of 1895.

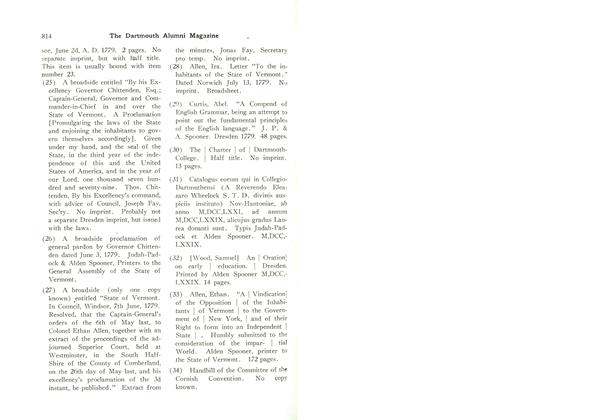

Among them are huge beams, bronze nails, lead pipes to convey water, bits of mosaic and sections of a marble floor. The objects of greatest artistic value, however, are three bronze lion-heads, two wolf-heads and one Gorgoneion or Medusa-head, which acted as ornamental end-covers of upright posts or horizontal beams. From the second ship comes a bronze cover of a beam end portraying in relief a forearm and hand, perhaps as a charm against bad fortune and the evil eye. In the jowls of the lions and wolves are mooring rings, evidently never or little used. The two wolf-heads, one of the lion-heads especially, and the Gorgoneion show a modeling which is firm and sure. The Medusa-head is of Hellenistic type and all are of the technique of the first half of the first century A.D. The two wolf-heads are particularly noteworthy for this: they are twin pieces, yet each shows variants, a fact which proves that they were modeled separately and were not merely mechanical reproductions of one original, as would be the case in the decorative art of today. These four are among the best examples of 'purely decorative bronzes that have been preserved to us from all antiquity.

From the sea, then, have come three great treasure- stores of art and ancient life which the water of centuries had covered and now reveals. The discovery of isolated statues goes on apace. A promising vista opens before us. With the perfecting of mechanical devices which daily defy the elements more and more, what may we not expect of artistic value or of historical fact from this new type of archaeological research?

"The project of uncovering the two Roman ships has at last entered upon the practical phase. The method which has been officially approved is that of a powerful electric pump discharging the water through the ancient emissary which ever since its construction has served to maintain the lake at a constant level. The preliminary operations, in which the level of the lake has been somewhat lowered and the whole extent of the emissary left dry, have permitted the detailed study of the emissary itself. ... At the moment of writing, June, 1928, further progress has been suspended in view of the necessity of making sure of the capacity of this venerable outlet to dispose of the volume of water, and to stand the rapid flow contemplated; a certain amount of reinforcing and adjustment of the channel will apparently be required before the full force of the pump can safely be brought into action. How long this will take and how serious the technical difficulties may eventually prove, can not be estimated at present; we may, however, hope soon to realize the dream of centuries and see the phantom houseboats of imperial Rome."

ONE OF THE ROYAL BARGES AS CONCEIVED BY THE ITALIAN ARTIST MANCINI. SOME BELIEVE IT A REAL SHIP WITH OARS AND A RUDDER, OTHERS PICTURE IT AS A LARGE FLOAT

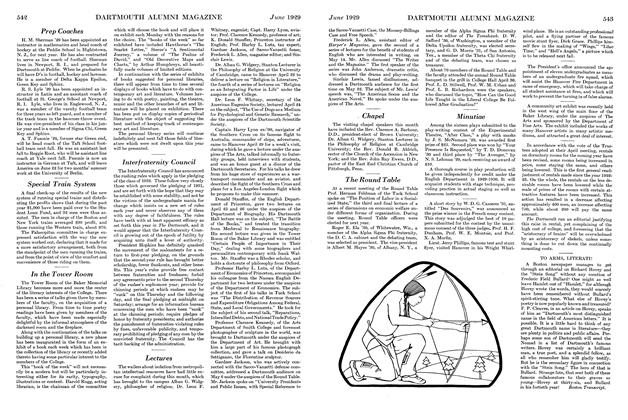

LAKE NEMI, NEAR ROME. THE TOWN LIES ABOVE THE LAKE. NEAR THE FAR SHORE IN THE LEFTMIDDLE GROUND IS THE SITE OF THE WRECK OF THE IMPERIAL BARGES

BRONZE WOLF HEADS USED AS DECORATIONS FOR BEAM ENDS. THE RINGS MIGHT HAVE BEEN USED FOR ROPES SECURING THE BARGES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Associations

December 1928 -

Sports

SportsSport for Sport's Sake, and—for Health

December 1928 By Robert J. Delahanty -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1928 -

Article

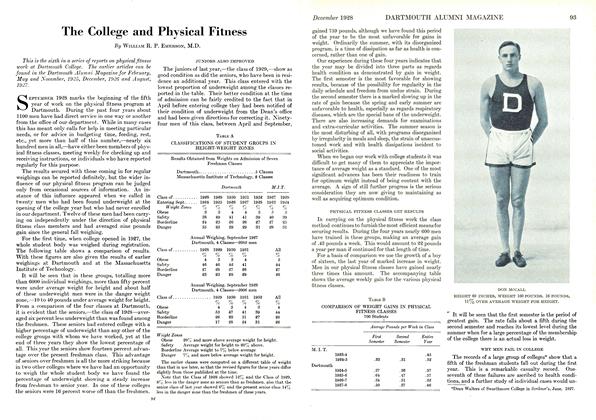

ArticleThe College and Physical Fitness

December 1928 By William R.P.Emerson, M.D. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

December 1928 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

December 1928 By Charles D. Webster,

Article

-

Article

ArticleTransportation Leader Honored

May 1955 -

Article

ArticleArts and Crafts Fair in Hanover, August 1-5

July 1961 -

Article

ArticleMural Money

FEBRUARY • 1988 -

Article

ArticleSpecial Train System

June 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleDANIEL CROSBY GREENE

May 1920 By Philip Sanford Mar den '94 -

Article

ArticleCharles Proctor

November 1940 By The Editor