This is the sixth in a series of reports on physical fitnesswork at Dartmouth College. The earlier articles can befound in the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine for February,May and November, 1925, December, 1926 and August,1927.

SEPTEMBER 1928 marks the beginning of the fifth year of work on the physical fitness program at Dartmouth. During the past four years about 1100 men have had direct service in one way or another from the office of our department. While in many cases this has meant only calls for help in meeting particular needs, or for advice in budgeting time, feeding, rest, etc., yet more than half of this number,—nearly six hundred men in all,—have either been members of physical fitness classes, meeting weekly for checking up and receiving instructions, or individuals who have reported regularly for this purpose.

The results secured with those coming in for regular weighings can be reported definitely, but the wider influence of our physical fitness program can be judged only from occasional sources of information. An instance of this influence appeared when we called in twenty men who had been found underweight at the opening of the college year but who had never enrolled in our department. Twelve of these men had been carrying on independently under the direction of physical fitness class members and had averaged nine pounds gain since the general fall weighing.

For the first time, when college opened in 1927, the whole student body was weighed during registration. The following table shows a comparison of results. With these figures are also given the results of earlier weighings at Dartmouth and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

It will be seen that in these groups, totalling more than 6000 individual weighings, more than fifty percent were under average weight for height and about half of these underweight men were in the danger weight zone,—10 to 40 pounds under average weight for height. From a comparison of the four classes at Dartmouth, it is evident that the seniors,—the class of 1928—averaged six percent less underweight than was found among the freshmen. These seniors had entered college with a higher percentage of underweight than any other of the college groups with whom we have worked, yet at the end of three years they show the lowest percentage of all. This year the seniors show fourteen percent advantage over the present freshman class. This advantage of seniors over freshmen is all the more striking because in two other colleges where we have had an opportunity to weigh the whole student body we have found the percentage of underweight showing a steady increase from freshman to senior year. In one of these colleges the seniors were 16 percent worse off than the freshmen.

JUNIORS ALSO IMPROVED

The juniors of last year,—the class of 1929,—show as good condition as did the seniors, who have been in residence an additional year. This class entered with the lowest proportion of underweight among the classes reported in the table. Their better condition at the time of admission can be fairly credited to the fact that in April before entering college they had been notified of their condition of underweight from the Dean's office and had been given directions for correcting it. Ninety- four men of this class, between April and September, gained 759 pounds, although we have found this period of the year to be the most unfavorable for gains in weight. Ordinarily the summer, with its disorganized program, is a time of dissipation as far as health is concerned, rather than one of gain.

Our experience during these four years indicates that the year may be divided into three parts as regards health condition as demonstrated by gain in weight. The first semester is the most favorable for showing results, because of the possibility for regularity in the daily schedule and freedom from undue strain. During the second semester there is a marked slowing up in the rate of gain because the spring and early summer are unfavorable to health, especially as regards respiratory diseases, which are the special bane of the underweight. There are al§o increasing demands for examinations and extra-curricular activities. The summer season is the most disturbing of all, with programs disorganized by irregularity in meals and sleep, the strain of unaccustomed work and with health dissipations incident to social activities.

When we began our work with college students it was difficult to get many of them to appreciate the importance of average weight as a standard. One of the most significant advances has been their readiness to train for optimum weight instead of being content with the average. A sign of still further progress is the serious consideration they are now giving to maintaining as well as acquiring optimum condition.

PHYSICAL FITNESS CLASSES GET RESULTS

In carrying on the physical fitness work the class method continues to furnish the most efficient means for securing results. During the four years nearly 600 men have trained in these groups, making an average gain of .43 pounds a week. This would amount to 22 pounds a year per man if continued for that length of time.

For a basis of comparison we use the growth of a boy of sixteen, the last year of marked increase in weight. Men in our physical fitness classes have gained nearly three times this amount. The accompanying table shows the average weekly gain for the various physical fitness classes.

It will be seen that the first semester is the period of greatest gain. The rate falls about a fifth during the second semester and reaches its lowest level during the summer when for a large percentage of the membership of the college there is an actual loss in weight.

WHY MEN FAIL IN COLLEGE

The records of a large group of colleges* show that a fifth of the freshman students fall out during the first year. This is a remarkable casualty record. One- seventh of these failures are ascribed to health conditions, and a further study of individual cases would

undoubtedly show that many of those who leave because of studies and finances have complicating health factors. At the Institute of Technology, in the class of 1923, only one man in three of those who entered graduated.

A college may justly be proud of its graduating class each year, representing as it does a group of men who have successfully completed the course—but how about the long line of men who had entered college having fulfilled all requirements and yet their hopes met with failure, a blow to themselves and to their families from which neither may ever fully recover? Our work has conclusively shown that a large percentage of these failures are due to conditions for which the student is in no way responsible—conditions that can be easily removed by a higher health intelligence on the part of the administration, faculty and the student himself. Although health education is rated as of first importance in our educational system, any study of its application may well raise the question whether it is not at present the very last in efficiency, f

SUMMARY OF HEALTH WORK

Our work at Dartmouth and with other colleges and universities shows results that can be summarized as follows:

First: In spite of claims to the contrary, a fairly comprehensive study of the student body in various colleges and universities shows that there is a steady increase in physical unfitness from freshman to senior year.

Second: The health intelligence (applied health knowledge) of the men grows steadily less pari passu with increase in physical unfitness.

Third: The health ratings obtained from the students themselves indicate a lower standard of health in a similar ratio.

Fourth: The first semester is most favorable for health—the second less favorable, and vacation time and the summer period most unfavorable of all.

Fifth: Physical fitness work has demonstrated in athletics that it is not the sport itself that breaks a man down, but improper training; that in college work it is not the demands of the curriculum or extra-curricular activities, but faulty health habits.

Sixth: As far as health is concerned it can be said in general that the higher the theoretical knowledge the lower the health intelligence—the longer the period of study the poorer the health.

This is shown by the fact that of the five causes of impaired health, namely, physical defects, irregularity of living (control), overfatigue, faulty food and faulty health habits, the last four grow steadily worse. The remedy for this condition is an increase in the health intelligence of administration, faculty and students and cooperation in removing the causes of impaired health. Thus it would be entirely practicable for every graduate to leave college with a high health intelligence, in full control of both physical and mental faculties,—physically and mentally fit.

Seventh: Here at Dartmouth the results of our weighings show that the tide has turned. Last year the seniors were 6 percent better off than the freshmen; this year the seniors show an advantage of 14 percent over the present freshman class.

NoTE: A well-known athlete, graduate of both college and law school, was sent to Saranac Lake with tuberculosis. He returned, having gained 60 pounds. He remarked, "The doctor told me, when I got there, that if I had not been ad— fool with regard to my health I would not have lost two years out of my life with tuberculosis." At the sanatorium perhaps the most important part of their work is to re-educate the patient in regard to his health habits.

In college and university it is from the group of the physically unfit, as identified by weighing and measuring, that the far too great number of those having tuberculosis and nervous breakdowns are recruited.

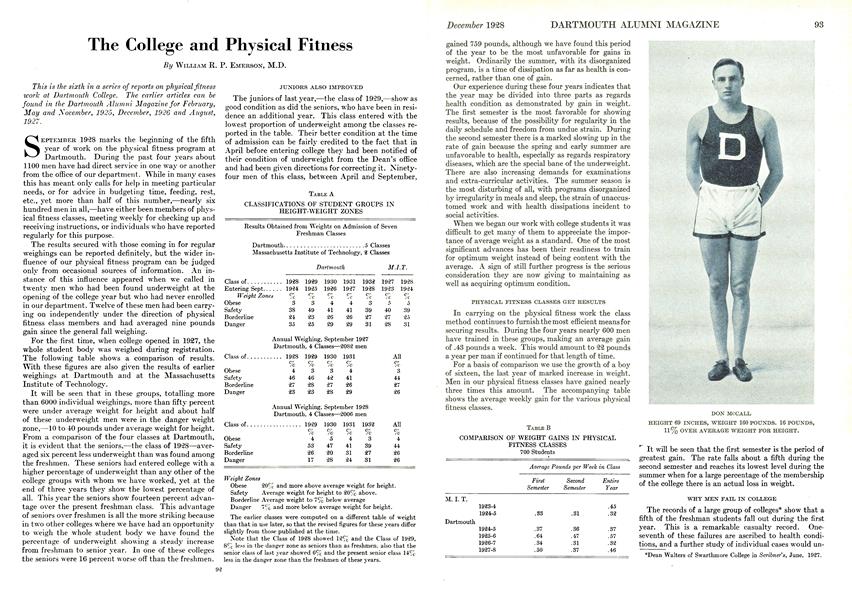

TABLE A CLASSIFICATIONS OF STUDENT GROUPS IN HEIGHT-WEIGHT ZONES

Results Obtained from Weights on Admission of Seven Freshman Classes

Dartmouth 5 Classes Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2 Classes Dartmouth M.I. T.

Class of 1928 1929 1930 1931 1932 1927 1928 Entering Sept 1924 1925 1926 1927 1928 1923 1924 Weight Zones %%%%%%% Obese 33 4 4 3 5 5 Safety 38 49 41 41 39 40 39 Borderline 24 23 26 26 27 27 25 Danger 35 25 29 29 31 28 31

Annual Weighing, September 1927 Dartmouth, 4 Classes—2082 men

Class of 192S 1929 1930 1931 All %%% % % Obese 4 33 4 3 Safety 46 46 42 41 44 Borderline 27 28 27 26 27 Danger 23 23 28 29 26

Annual Weighing, September 1928 Dartmouth, 4 Classes—2006 men

Class of 1929 1930 1931 1932 All %%% % % Obese 4 5 4 3 4 Safety 53 47 41 39 44 Borderline 26 20 31 27 26 Danger 17 28 24 31 26

Weight Zones Obese 20% and more above average weight for height. Safety Average weight for height to 20% above. Borderline Average weight to 7% below average Danger 7% and more below average weight for height.

The earlier classes were computed on a different table of weight than that in use later, so that the revised figures for these years differ slightly from those published at the time.

Note that the Class of 1928 showed 12% and the Class of 1929, 8% less in the danger zone as seniors than as freshmen, also that the senior class of last year showed 6% and the present senior class 14% less in the danger zone than the freshmen of these years.

TABLE B COMPARISON OF WEIGHT GAINS IN PHYSICAL FITNESS CLASSES 700 Students

Average Pounds 'per Week in ClassFirst Second EntireSemester Semester Year

M. I. T. 1923-4 .45 1924-5 .33 .31 .32 Dartmouth 1924-5 .37 .36 .37 1925-6 .64 .47 .57 1926-7 .34 .31 .32 1927-8 .50 .37 .46

DON MCCALL HEIGHT 69 INCHES, WEIGHT 160 POUNDS. 16 POUNDS, 11% OVER AVERAGE WEIGHT FOR HEIGHT.

MONTY WELLS HEIGHT 71 INCHES, WEIGHT 162 POUNDS. 8 POUNDS, 5% OVER AVERAGE WEIGHT TOR HEIGHT

*Dean Walters of Swarthmore College in Scribner's, June, 1927.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

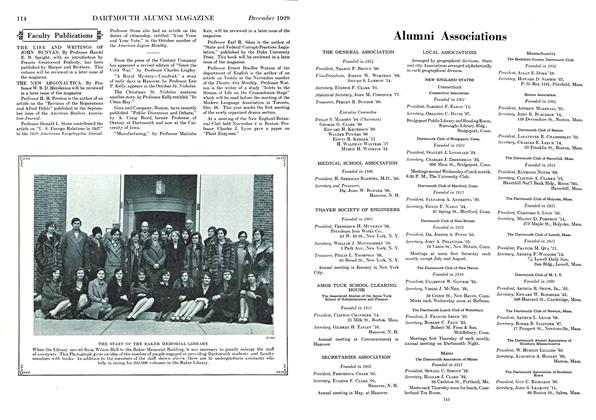

ArticleAlumni Associations

December 1928 -

Sports

SportsSport for Sport's Sake, and—for Health

December 1928 By Robert J. Delahanty -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1928 -

Article

ArticleClassical Art From Ancient Shipwrecks

December 1928 By Professor William Stuart Messer -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

December 1928 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

December 1928 By Charles D. Webster,

Article

-

Article

ArticleJUNIOR WEEK

JUNE, 1907 -

Article

ArticlePresident Announces Other Appointments

October 1948 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

NOVEMBER 1969 -

Article

ArticleUndergraduate interns add student perspective to DAM

NOVEMBER 1986 -

Article

ArticleSimian Sensibility

Nov - Dec By Judith Hertog -

Article

ArticleA Preacher Against War

MARCH 1966 By WARNER B. STURTEVANT '17