For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

May 1929For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

THE NEW TUCK SCHOOL

WHEN Eleazar Wheelock came to Hanover in 1768 he found the ground now designated "campus" covered with tall pine trees. It did not at first occur to him, if traditional history tells us truly, to utilize that flat area, but he cast his eyes upon two hills, one of them known as Mt. Support on the short road to Lebanon, and the other the low hill located at the foot of Tuck Drive and overlooking the river. Mt. Support proved too marshy, and the hill overlooking the Connecticut had no springs for drinking water, and therefore a settlement was begun first in the field near Hitchcock Hall, where the memorial boulder now stands and later at the present campus edge. It has taken just 161 years for the College to move to the site chosen originally by Wheelock as his college site, and this time the trick has been turned by the Amos Tuck School of Business Administration.

The radius marker of the College is now sweeping to the extreme left of the College grounds with the new Baker Tower as the center. According to the plans released by the administration for publication, the new Tuck School will consist of a large central building for class, conference, and research purposes, two flanking buildings to be used as dormitories, and a fourth building to be used as a dining hall. The necessity for the expansion of the Tuck School is quite obvious, and its growth, as well as its establishment, is due presumably to Mr. Edward Tuck. The general propositions of the college man in business and the necessities for preserving and creating business ethics are also considerations that one takes into mind when this new group of buildings is proposed, but there is one side of the matter which is of particular interest to Dartmouth men.

America safety for their charters, the college idea became the dominant idea at Dartmouth for all time. And that is the place of the college as distinct from the university in the American educational world. Dartmouth is a college, and will continue to be a college both because of its traditional and historical record and because of its charter and aims. Few educational institutions can say that they tried both college and university systems and discarded the university idea. Yet that was exactly what Dartmouth did. In the years between 1790 and 1810, Dartmouth, graduating as many students a s perhaps any other American institution of learning, was known alternately as College and University. The old 18th Century catalogues were printed with the university heading. And in the noteworthy battle in which the College triumphed over the University and thereby assured for all Colonial colleges in

The college has been said to be America's unique contribution to the educational world. And yet the limits of the college have never been defined. Broadly it has been said that the college takes young men between the ages of 18 and 23 and provides them with—what? even the what has been in question but it involves the exposure of the student to cultural things, an acquaintanceship with books and men interested in men and books, health-giving habits, some knowledge of other men,—beyond this the college hopes to bring men to a thinking consideration of the greater values of things, religion, ethics, citizenship, and loyalty.

But the college, even as the university, must meet the conditions of the world as it exists, and the fact can not be denied that a man should be given some knowledge of the conditions which will surround him when he embarks upon the career to which his natural tastes and impulses lead him. It does not mean that the college becomes a training school, indeed it can not compete with the highly efficient training schools which as such offer professional careers nor does it aim to compete. It has no intention of doing so. But it can provide the general outlines of the specific environment in which a student is to find himself in after life,—hence the new system of major studies, the departmental comprehensive examinations, and the approaches to careers in engineering, medicine, teaching, or writing. There is no attempt to narrow the field by the teaching of specific technique.

But with the new absorption of the world in business the greater number of students graduated from Dartmouth enter business after education. Even the college can not be blind to this fact. Mr. Tuck saw this trend many years ago, even at a time when the ministry, law, medicine and teaching occupied the attention of most college men, and the old curriculum was after all adapted to these professions, despite the fact that such training, preliminary though it was, held much of general cultural value. The same has become increasingly true of business which has broadened its scope immeasureably in the past 25 years. Under an older competitive system which demanded that buyer and seller try to outwit each other, the chief example in literature is the recently translated novel of the realist Ladislaus Reymont and bearing the name "The Promised Land" in which men who formerly possessed cultural interests and high ideals fought like beasts in the old "Russian Manchester," the present city of Lodz in Poland. The position of college men in the business world certainly is a tenable one if students can enter business with a broad training in cultural things, with high standards of ethics and honesty. After all the highest purpose of the college is to serve the state, and without becoming a university or a training school it can send men out ready to stand for such principles, and if necessary later on to receive more detailed training in other schools, which do specialize in a more technical way.

Thus the swing to the left toward the river. The old Tuck school building becomes a part of the College of Liberal Arts which now dominates the campus. The new group of buildings located on one of the most beautiful spots in Hanover marks a development in the new growth of the College, when a time has come to regard the College not as a single unit but as a composite of smaller units all with their own interests. The new Sanborn building takes the English department out of Dartmouth Hall and gives that department a better chance to develop individually. The same is true of Carpenter as it concerns the Art department. The separate housing of departmental sections has been going on for years, and will probably go on for many more. And the new Tuck group is in no way a concession to Babbitt,—it is an application of the academic function to business life by a man who has been more than ordinarily successful in the worldly sense of business success who saw many years ago the place of the cultured and educated man in the business world. And since business seems to be one of the ruling passions of American life the extension of cultural influences among business men may be one of the ways to prevent Babbitts.

WHICH COLLEGE?

AMERICAN education seems to occupy the place of . honor among the current periodicals, for there is scarcely a magazine of the month or week that does not deal with some phase of undergraduate life, from the Outlook's Utopia College to Harper's Young Men on theMake and a number of others scattered here and there. And the average American unconnected with an institution of learning is quite likely to read this material and feel more or less unconcerned about the matter, unless it so happens that a son or daughter is being graduated this year from a high or preparatory school and is quite uncertain about a college future. Then the whole atmosphere changes, "the horizon shifts three quarters the way around" as Ambrose Bierce once put it, and the whole college question becomes a vital and a pressing issue. The time is not far away when the high school career of many a son or daughter is drawing to a close, and many last-minute frantic decisions are being made. Is it to be a training school or an institute? Is it to be a technical school or a trades school? Is it to be a small college or a large college, or is it to be a state university or a chartered university? The boys and girls who show decided tastes in art or music or designing find their particular schools quickly. But the greater number remain almost undecided until they find themselves in a college town to which parental prejudice or their own whims may have brought them. And the curious sequence is, that these students brought usually by chance to a higher institution of which as a rule they knew nothing except by hearsay,—these students in later years seldom if ever regret the choice that has been made. That is the curious part about it, and it speaks in the highest manner for the general run of American institutions of higher learning. The writer of this editorial can not remember one instance in which he has heard an alumnus of a college speak slightingly of that college or fail to resent any unfair or hostile criticism of it. One conception of college loyalty is the influence which draws men to cheer for a team at a football game; another conception is the influence which causes the alumni to contribute generously to the support of the college that gave them things of cultural value; this conception is the idea that most men would receive benefit from any college, and consequently are loyal at heart to these colleges from which they were graduated and the striking part of it is that few men ever say "I wish I went somewhere else."

WHAT to DO?

DEAN BILL'S interesting article on the entering class (1932) revealed among other things that out of 586 freshmen interviewed at the threshold of their collegiate career, only 281 knew what their proposed vocation was to be in life. Last year, out of 626 freshmen a number much smaller (proportionally)—to wit, 278—were devoid of doubt as to what they were ultimately to do. One vaguely suspects that the answers made by the rest are worth but little, for a boy just out of the preparatory school is quite likely to change his ideas as he grows toward graduation from college. Still there are always some with what is called a "bent" sufficiently developed to warrant but little speculation as to what form of activity will be best to pursue.

What one doubts most of all is that forecasts made thus early in life can be worth basing courses of special study upon—indeed at Dartmouth the tendency has been to demand the postponement of specialization until the last two years. Probably a very considerable fraction would have to say, even at the moment of receiving their degrees, that they were still without a very definite idea of what sort of job they intended to seek. It means comparatively little when 105 freshmen announce that they intend to go into "business"—it was 105 last fall, and 125 a year ago. Much more definite is it when 78 say they hope to follow the law, or 45 that they intend to fit themselves to practice medicine.

The class of 1931 had one member who professed to a desire for the study of theology. Is he still of that mind? In 1932 there is not even one. The recruiting of the ministry has come to be a most serious problem in this age. Only 10 of the present freshmen announce a desire to become teachers—a calling which, for a guess, will be followed by many among those who don't yet know what they are going to do. Ten others would be journalists, and 29 hope to be engineers—that field, however, is broad enough to make the term almost as elastic as "business." The catch-all that gets the finally undecided is at present likely to be either bond salesman or insurance.

In freshman year uncertainty matters little—perhaps not at all. Nor is it particularly important in sophomore year, either. The main thing is to get a liberal education, useful no matter what one goes into for a livelihood, and largely with the idea of making a young man capable of enjoying his living reasonably when he gets it. The ages of 18 and 19 are o'er young for the tasks of specialization and it is usually better not to begin prematurely, even in this age when apprenticeships are long and are unproductive of much pay. In fine it is difficult to feel any pity for the men who don't yet know what they expect to do for a living. In a sense it's better they shouldn't have too rigid ideas about that quite so early.

THESE NEW FELLOWS

BUT for the chosen, extra-special, ultra-intellectual few it may work well." With these words the ALUMNI MAGAZINE expressed itself on the new plan at St. John's College in Annapolis a short time ago, the plan which allows certain selected students of the senior class (never more than five) to spend the entire academic year as they choose, sans tuition, required attendance, curriculum requirements, examinations or any of the specified duties which their less gifted or less industrious mates must perform. These men, selected by the Administration, are turned absolutely loose to wander as they choose, to browse in the academic meadow when, how and in what manner they choose. And now it'scome to Dartmouth. The St. John's plan, with certain modifications, is to be tried out at Hanover under the terms already made public. Five Dartmouth seniors in the next academic year thus go vagabonding in excelsis. They are chosen by the trustees from candidates whose names will be submitted by President Hopkins after he has held a conference with the deans, members of the faculty and various committees.

In its way this new scheme, and it is experimental at present, works in a startlingly different direction from the course adopted by many colleges and universities. That course, which seems to have gained great favor of late has been called "orientation." It has been taken for granted that the student at 18 when he arrives at a college is not fit to assume his full responsibilities and therefore must be instructed in the ways of college and university life. In similar ways the "orientation" system follows the student through college and he is thrown out into a hard and seemingly unfeeling world where there is but little "orientation." In other words the orientation" system delays until the latest possible time the day when the student shall assume full responsibility for himself. However, the earlier that adjustment comes, the less friction there is involved in it. One does believe in signposts for freshmen and even upper classmen and the same sort of kindly direction that is found everywhere, but it is possible to do too much for undergraduates and seriously harm them by robbing them of the sense of individuality and initiative which they should gain in college. The foreign university, as a rule, leaves much of this to the student. He makes his own arrangements, lays out his own expenses, finds out for himself about his studies, and as a rule spends a month or two of considerable pain and anxiety becoming acclimated to the responsibilities of life. But he must meet this at some time or other, and college might better furnish it than the first business job that he takes.

The new idea is in direct opposition to paternalism as such. It will offer to undergraduates the chance of a year in which they may have all the cultural advantages of the college and none of its discomforts. It will put a premium upon initiative in cultural things,—indeed it will cultivate initiative if it cultivates anything. Opponents of such a plan would say that no college curriculum is of value unless men are made to work; that class rooms would be empty if men were not obliged to be present; that even high students are more interested in marks than in subjects; that the whole system of college work might break down if the principle of voluntary attendance and study were spread through the college body. They would quote the case of Chapel which certainly declined in attendance after compulsory chapel was abolished.

But the experiment is going to prove many things to the people who are interested in education. It is going to prove whether or not college men are capable of being thrown "upon their own." It is going to prove whether or not subjects in the curriculum have an interest of their own, and it will also prove which subjects have the most appeal. Those who have confidence in the student of the present day, and this President Hopkins has to the highest degree, are going to learn just what the frank opinion of these students about the work may be, and it may possibly throw light upon methods of teaching and the kinds of teaching which prove the most stimulating. Certainly the selected students will not attend classes in which they are not in some way interested; however, attendance at a class in a subject which actually repels them may be brought about through curiosity concerning the personality of the teacher or the method of approach to the subject. From the point of view of the educator the experiment is going to mean a great deal.

What is the student to gain? The opinions of the five men who go through 1929-30 vagabonding de luxe will probably be reprinted in every college publication in the country. At this point we may venture to say what we think they will gain, though we have no means of knowing exactly. They may gain a new knowledge of their own college, they may broaden the field of their work by being freed from the rather narrowing concept of a "major study." They will hear more men lecture and they will hear more classes discuss. They will see the whole process of education as a whole and not as a series of "compartments." But best of all, it seems to us, they will gain initiative. When the system ceases to be paternalistic in their cases, they will be thrown back entirely upon their own resources. It is to be hoped that they will not organize nor have "faculty advisors." They should get the important feeling that lies back of every worthwhile endeavor, the feeling that in one's self is the beginning and end of all achievement and all progress.

A COVERED HOCKEY RINK

If the sport of hockey is to develop in Hanover as it has this year it is probable that some kind of covered stand will be necessary for the players and spectators. The Outing Club's experiment of building four outdoor rinks on Occom Pond had most satisfactory results, for all these rinks were in constant use, and after they had been scraped off each day by a gang of men and two teams of horses the eager crowd gathered to chase the puck and shoot at goals. The varsity rink near the Alumni Gymnasium was also in constant use, mostly for practice by members of the various college teams, varsity, freshman, and recreational. The winter was a favorable one, and the scraped ice was sufficient for home games, although progress was delayed in most of them by the necessary procedure of ice scraping which came not only between periods but even during the course of the game. The result was that only three or four local games had to be called off because of poor ice instead of the usual seven or eight. In the past five years the winters have been poor hockey winters and the hockey teams have been obliged to go without practice or shift their games to covered rinks in the cities.

But with the wholesale interest developed in hockey this winter it seems almost necessary to make provisions against the sloppy winters that Hanover is subject to. The original plans of the hockey layout called for two rinks running from north to south, and two rinks would be none too many for the large numbers of men electing hockey as a recreational activity. However, the attendance at the "big" games was unusually large this year, and the spectators braved some rather zero weather to watch the teams play. The team games have the value of stimulating hockey play among the recreational groups, and yet there is danger that through the uncertainty of Hanover winters the number of such games may drop considerably. This means, or possibly will mean, the scheduling of such important match games in the city, possibly Boston, where the ice is always constant inside the covered rink. Such a step is not in keeping with college sentiment. The only alternative is the providing of some kind of shelter for the ice, players, and spectators.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA Survey of Undergraduate Activities

May 1929 By Carl B. Spaeth -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1898

May 1929 By H. Phillip Patey -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1923

May 1929 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

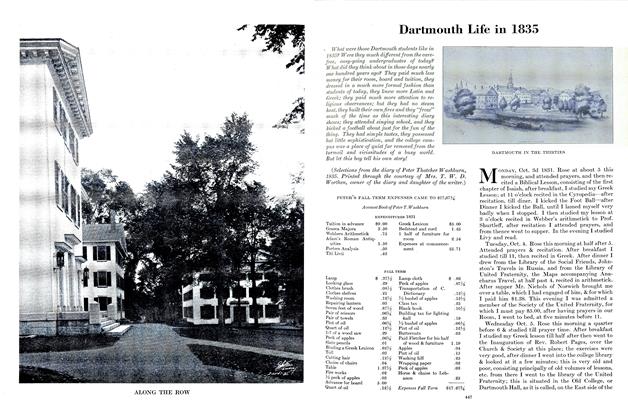

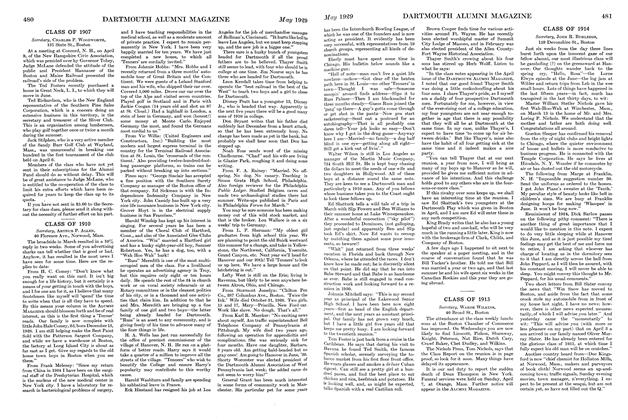

ArticleDartmouth Life in 1835

May 1929 -

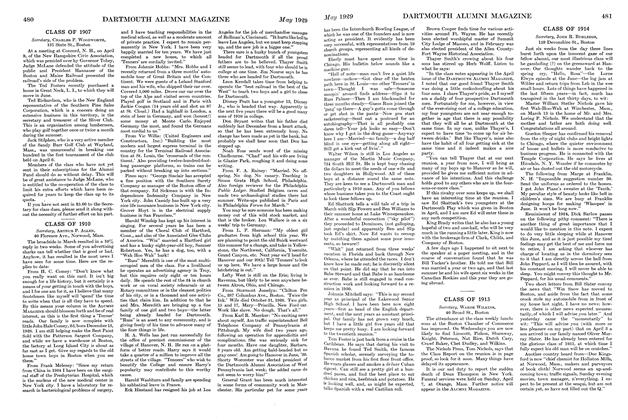

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1929 By Arthur P. Allen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

May 1929 By John R. Burleigh

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

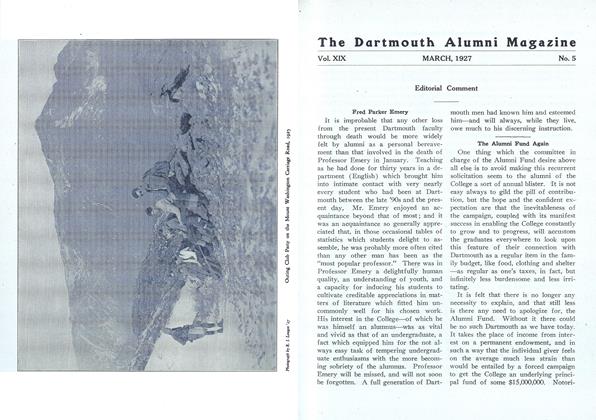

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MARCH, 1927 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

OCTOBER 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

April 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorIn Keeping With This Month's Cover Story, The Review Barks Up Dartmouth's Tree.

MAY 1992 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWinter and Rough Weather

DECEMBER 1983 By Doug Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorResponse: The Real Women's Issues

MAY • 1988 By Mary G. Turco