For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

THE ALUMNUS AND HIS COLLEGE

WHEN President Hopkins told the representatives from several hundred colleges and universities at the Amherst meeting of the American Alumni Council last month that the alumni body of a college is the college, he put into words an idea that has been lying unexpressed in the minds of nearly all Dartmouth men. It brought to mind an incident which happened at a dinner given by the alumni to a graduating class some years ago, when the toastmaster, a distinguished Massachusetts jurist, called for a cheer for the "freshmen," meaning, of course, the men who had just received their degrees. The "freshmen" were rather surprised at the wording, since they believed that they had long since outgrown that term, but the laughter which followed the first gasp showed that the point had been driven home—that graduation from college was merely the entrance to the great organization, the alumni.

It is rather a magnificent thought to one who is a member of a college community to feel that the immediate college at hand is but the living symbol of the interest and concern of thousands of alumni scattered all over the earth. It thrills one to think that a piece of news bringing information of new achievement, progress, or deed well done will quicken the hearts of all the graduates, and it makes one realize as well the pain and chagrin that comes to these same hearts when the news of something unfavorable is reported. The success or non-success of athletic teams brings only ripples of pleasure or disappointment; serious letters begin to pour in to college officials only when alumni believe that changes in policy or administration are concerned. And while the college is the alma mater to its undergraduates it stands perhaps in the position of a,favorite child to the alumni and each alumnus who concerns himself with an expression of opinion regards the college as a thing distinctly his own. The sum total of this individual feeling of ownership marks the college as a symbol upon which is focussed the attention and regard of all the alumni.

And in saying that the college is the alumni, one quickly disposes of a number of trite phrases such as "if it wasn't for the alumni we could do this or that," or "the alumni are a great nuisance" or "the alumni care only for football tickets." One need only edit an alumni publication and read the letters which come to the office, letters which do not find their way into the "letter column" because of requests on the part of the writers. These letters for the most part show the greatest concern in the really vital things of college, the curriculum, the health of the students, the maintenance of worthy traditions, and the tone of all letters is the tone of an anxious father solicitous for the welfare of a child.

THE SECRETARIES

WITH the organization of the Dartmouth Secretaries' Association in 1905, there began the history of a group which today occupies a position of first rank importance in the yearly life of the College. Made up of the secretaries of all classes and associations the organization represents a cross section of Dartmouth's 14,000 alumni—of the alumni chronologically by classes and geographically by clubs and associations.

When the secretaries hold their annual meetings in Hanover the town becomes theirs for a week-end. Just as the opening of college, the annual big game, Carnival and Commencement, are occasions well marked on the calendar by their traditional observance, so the Secretaries' Meetings early in May have come to take on the significance of an Annual Event. Nearly one hundred alumni coming each year from all sections of the country take their place each spring as the guests of the College for the two days of their meetings.

A reception at the President's House welcomes the secretaries. A business session precedes the annual dinner, marked by the President's address, and a second business meeting follows on Saturday morning. New buildings are to be visited in the afternoon. Lacrosse, baseball, golf and tennis leave little time until the informal dinner at the Outing Club House with a showing of the latest movies sponsored by the Association. Then to a show in Webster Hall or to leisurely reminiscing at the Inn.

Leaving Hanover Sunday the secretaries are conscious of being again completely and thoroughly well informed about the College. Speakers have told them of the latest developments in the curriculum, in the plant, and in the activities of the undergraduates. Discussions have shown them ways of improving their secretarial work. And they are appreciative of the College's hospitality.

THE BACKWARD SWING

SOMETIMES we wonder just how genuine this current undergraduate insulation from enthusiasm actually is. Some phases of it certainly are real enough. They refuse (audibly) to accept traditional doctrines or critical evaluations as binding—usually because generations of their academic predecessors have found value therein.

Football games are supposed to attract the average Dartmouth junior much less than the orbit of dances and parties that surround them. Interclass fights have been dismissed as "young." Hums are almost extinct. Delta Alpha is on the wane. It is unfashionable to be at all impassioned about Shelley. To admit an interest in the life of the College antecedent to the Selective Process regime is rare. Not that all tradition has left the Campus. Seniors still sit on their own senior fence and carve canes elaborately. Wet-down and Sing-out still exist as tangible ceremonies. Still, there is no doubt that tradition has hit a new low during the last few years.

And yet—these inter-fraternity baseball games on the campus of May afternoons have been drawing real crowds. One day last week we counted over four hundred spectators—most of whom were cheering every three-bagger with a vehemence that sounded suspiciously close to enthusiasm.

And this interest is quite new. Games of the last two years drew no such crowds. Curious, we asked one of the spectators: "Why the interest?" The answer was as we expected: "Oh, nothing else to do." Which wasn't quite true. We feel sure that the real reason was just a tiny impulse of the pendulum away from overemphasized skepticism back toward normal undergraduate daring to break a lance for spontaneity—perhaps less "vital," but certainly much more interesting than attitudinizing.

SHORTS

WHY not? Twenty-two hundred Dartmouth undergraduates have shown a skeptical world that a revolutionary innovation in male dress can be effected, even though this be done, somewhat more easily, in the isolation of a New Hampshire village. Movie and newspaper cameras clicked about the campus recently when the 600 pioneers of the "Shorts for Comfort" crusade appeared in abbreviated costumes. Braving chill winds the pioneers came forth "free and kneesy" to be greeted with the smiles of the less courageous. Within a few hours a pair of unclad legs and bare knees drew no more attention than the same legs and knees would have attracted had they been clothed in flannels or knickers. "The Declaration of Knee Independence" had been accepted.

On first look visitors to Hanover will perhaps gasp. But, surprisingly, onlookers seem to favor the shorts. Some legs and knees bear the scrutiny of public gaze to greater advantage than others, but all appear cool and comfortable.

It is significant that the adoption of shorts for Hanover wear is the first concerted undergraduate movement in several years. Not since the breaking down of old traditions in 1924, headed by the abandonment of the picture fight by the class of 1926, has The Dartmouth crusaded as energetically or has the student body responded as unanimously. Critics of the 1930 college generation could receive little encouragement from the joyful and spontaneous support given to the Shorts Campaign—something new and different, serious enough to take pride in but amusing enough to be smiled at.

ADEQUATELY EQUIPPED

DURING this last week of fine weather, we have seen the Dutch Colonial roof of the new dormitory group behind the Fayerweathers go on almost by magic. When this triumvirate, christened: Woodward, Ripley, and Smith, goes into service this fall the housing schedule of the College will be definitely completed for the time being. The off-campus dissociation of a large group of men who have always preferred to live in dormitories but because of inadequate facilities have never been able to is now an evil of the past. The completed grouping of the student body into college-owned buildings should make for a tightening of class and dormitory spirit.

The college plant now provides living quarters for 1661 men. The fraternity houses accommodate 416. This leaves less than two hundred men without an oncampus residence. The administration feels that there will always be about that number of men, who, for various reasons, will prefer to live in private houses. Over ninety percent of the College will next fall live in twenty-two dormitories. More than three-quarters of this space is completely fireproof and only nine percent is unable to resist fire.

Hubbard is to go and Reed is to be redesigned for classrooms as was its companion, Thornton. Richardson is to be overhauled and some of its large rooms partitioned for a few additional single rooms. Of the wooden dormitories, Crosby alone will remain; and only part of Crosby is wood-framed. Apparently safety from fire hazard outweighs sentiment in the new building program as can be seen by the abandonment of South Hall, Sanborn, Culver, and now Hubbard.

It is interesting to find that for the first time graduate students will be allowed to share undergraduate dormitories. The Tuck School Unit provides accommodations for instructors, graduate students and undergraduatesall under the same roof. It is undoubtedly true that there will be additional cultural advantages in the proximity of men of all classes who are studying varying subjects. As far as possible the administration tries to allot rooms so that incoming freshmen make up forty percent of the personnel of each dormitory and to give dormitory rooms to all members of the entering class.

The prices of dormitory rooms next fall range from eighty dollars to three hundred and twenty. The rentals of approximately fifty percent of the rooms fall into the scholarship requirement group. It is specified that no scholarship man shall spend more than $180 per year for room rent. In other words, Dartmouth now has more rooms at or below this figure than it has scholarship recipients to live in them.

It is something of a relief to feel that Dartmouth now has sufficient physical plant to house everyone adequately and to definitely centralize undergraduate life around the campus.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

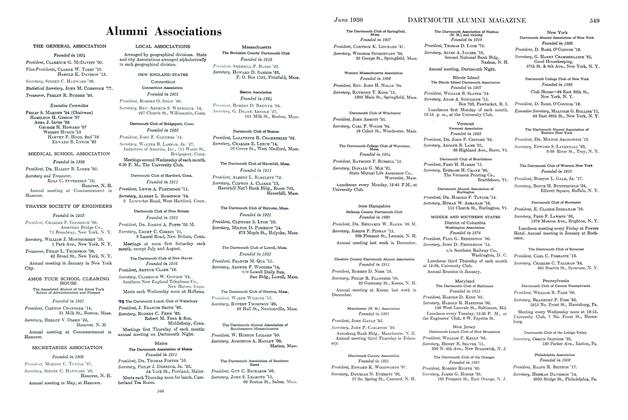

ArticleAlumni Associations

June 1930 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Indians

June 1930 By Leon B. Richardson -

Article

ArticleThe Use of Leisure

June 1930 By Nelson A. Rockefeller -

Article

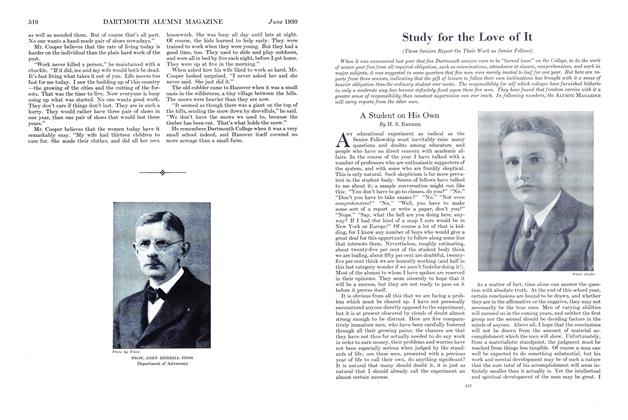

ArticleA Student on His Own

June 1930 By H. S. Embree -

Article

ArticleTrustee Meeting

June 1930 -

Article

ArticleOpening Windows

June 1930 By John French, Jr.

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

FEBRUARY, 1927 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLORD DARTMOUTH WRITES OF DARTMOUTH HOUSE

FEBRUARY, 1927 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA LETTER FROM ED STOCKER

January, 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPassages

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorOn Being No. 1

MARCH 1984 By Douglas Greenwood