BY PRESIDENT ERNEST M. HOPKINS

IN ancient times men built their temples so that worshipers at the altars should face the rising sun. The location of a structure, thus to face the light, eventually came to be defined by the verb "to orient." Thence the noun "orientation" was developed as significant of articulation with and adjustment to one's environment. This word has been largely adopted by formalized education as expressive of certain clarifying processes which are deemed essential to making its work effective.

Today, orientation is my theme. The subject is too large and too complex to discuss in detail or to attempt to carry through to completion. There will, nevertheless, be advantage if, in the consideration of a few assertions, we can approach understanding of the life about us and of the essential connections with and relationships to an environment which we have sought, and in many cases sought without any large acquaintanceship with its attributes.

I desire particularly to speak of mutual relations between the undergraduate body and the institutional college. I have used the word "sought" deliberately in speaking of undergraduate membership because that word is descriptive of the fact.

Specifically, at Dartmouth, as at a number of other colleges, there are far more who seek enrollment than can be accepted. Dartmouth consequently strives to select from among applicants those who will be most understanding of its purposes, most receptive of its ideals, and most capable of utilizing its advantages.

A college gives no man an education but it gives to all men who associate themselves with it the opportunity to become educated. The major emphasis of the college is to teach men how to seek knowledge rather than to state what knowledge is.

Today, Dartmouth offers to men who seek education the guidance of scholars and the supplementary advantages of plant, equipment, and facilities to unprecedented degree. It moreover offers the heritage of a great name and fellowship in a world-wide association of men, rendering to society distinctive service in their respective fields of accomplishment.

COLLEGE MUST MAINTAIN ITS IDEALS

A disgruntled Sophomore wrote to his parents two years ago, explaining his having been put on probation, in these words, "It's a great misfortune for undergraduates here to have the College so popular. It makes Dartmouth too independent." In response, I said to the father that the public esteem in which the College was held was undoubtedly a misfortune for men who wished to arrogate to themselves the College privileges without any regard to their reciprocal responsibilities.

I should say the same now. Dartmouth has been given distinction throughout a life longer than that of the nation by a host of men who have contributed their careers and their lives to enabling the College to render its acceptable service to mankind. Meanwhile, its benefactions all represent solicitude for the preservation of its ideals, in many cases represent sacrifice, and in some cases represent something near to self-impoverishment in order that the opportunities for succeeding generations of youth may be made richer and more ample.

The material facts relating to College support are not as vital as the intangibles behind them but they can be more definitely stated. Last year, to cite a single instance, five thousand, six hundred and eighty-three alumni contributed according to their means to the financial support of the College. If any are interested in specific details, the cost of what Dartmouth offered to its students last year, not including any construction expense, was one million, six hundred and thirty-three thousand dollars and the sum total of all undergraduate payments for this was eight hundred and nine thousand dollars,—a little less than fifty per cent. It is against such a background that the official College seeks to fulfill its trust, to enlarge its accomplishments, and to return to society worth cumulatively greater from year to year.

From such considerations as these, it comes about that the college faculties and college administrative officers feel obligated to restrict college opportunities to undergraduate constituencies which will appreciate their values and will make honest endeavor to utilize them. It is likewise from such considerations that college officers are forced to hold due reservation and to remain only mildly impressed by eloquent contentions that colleges exist solely to satisfy the wishes of the undergraduates. Rightly interpreted, the argument is sound, but usually it is not rightly interpreted. The perspicacious college will be far more solicitious to provide the man the undergraduate is to become with what he will hold to have been valuable to him than to provide what a nebulous undergraduate sentiment, which periodically vacillates according to cycles, appears to desire at any given time.

I do not mean by this that the official college should ever make itself inaccessible to the opinions and desires of the undergraduates or should be unwilling to weigh the merits of arguments which they may submit in regard to the conduct or the policies of the college. I do mean that what seems best for mankind as a whole cannot be forgotten or ignored in college management for the specious satisfaction of conforming to an ephemeral undergraduate opinion or the desires of self-centered individuals.

MANY TYPES OF "COLLEGE"

Having spoken of the necessity that a college shall hold to its ideals, let us consider the kind of a college which we have sought and with which we now become associated. I have used the term "American college" and shall use it again as descriptive of a period and of a manner of higher education indigenous to the American people. Within that classification, however, there are many subdivisions of type and variety of objectives characterizing different groups of colleges.

The technical schools exist for teaching how to do specific things. These in the main have minor concern for such abstractions as speculative thinking to determine the social value of the thing done. Then, also, there are colleges wherein the undergraduate course is given over largely to vocational work. These tend to restrict the consideration of knowledge and the development of ideas within the specific limits of the vocational fields for which these colleges give preparation.

There are, also, arising now the junior colleges, which proffer a truncated course and will in time, doubtless, offer a short cut to the professional schools and graduate schools of some of our major universities.

Lastly, there are the undergraduate departments of great universities where oftentimes emphasis tends to be put upon the undergraduate work as a preparation for the graduate schools. Let me add, however, that in universities which have evolved from historic colleges, such as Harvard and Yale in New England, such coloring of the undergraduate course is at a minimum.

OBJECTIVES OF THE LIBERAL COLLEGE

In contrast to all these, there stands the independent liberal college with an inclusive field of its own, such as Dartmouth is. It is reasonably clear what are the respective interests of the technical school, the vocational school and the junior college, as well as what may be the primary interest of the undergraduate department of a university. It is a little more difficult to define the purpose of the liberal college.

It was an underclassman of our own group who remarked two years ago that he didn't see where Dartmouth got off in its claim to be known as a liberal college since it had one of the highest tuition charges in the country.

The liberal college is interested in the wholeness of life and in all human thinking and in all human activity. Its consideration is given mainly to the common denominators which make for fullness of life rather than with exclusive interests which ignore vital phases of human existence. It is characterized as liberal because it recognizes no master to limit its right to seek knowledge and no boundaries beyond which it has not the right to search. Its primary concern is not with what men shall do but with what men shall be.

The objective of the liberal college is to stimulate minds to activity in consideration of present-day problems under restraint of lessons of the past and under spur of imagination as to the possibilities of the future.

The inactive mind may be dismissed at once as futile in itself and useless to all mankind. The active mind, which interests itself in the past, to the exclusion of all else, has to depend on the written word and produces the bookish man. The mind in ferment which looks to the future alone as worthy of attention must remain oblivious to the accumulated wisdom of the ages in experience. This mind is subject to the hazard of a thousand avoidable mistakes in comparison with any possibility of having one idea of worth.

Mankind at large has never completely understood the civilization of its own time but interpretation has come most largely to generations whose prophets have been seers who have visualized the future through clear vision of the present and of the past. An individual or a generation which ignores its continuity with the past is incapable of understanding its relation to the present and renders itself sterile for participating in the future.

SELF-DETERMINATION OP UNDERGRADUATES

Such are some of the reflections from which the methods of this college have evolved. Transferring our attention at this point from responsibilities of the in- stitutional college to those of the undergraduate body, what may advisedly be said to these members of the college as to their own self-determination of what their place is to be among the men of influence in life subsequent to college days?

Each college generation is characterized by a spirit of its own. The causes of this are usually obscure. The effects, however, are easily discernible to one who makes study of college history or even to one who has acquaintanceship with the life careers of men graduating in a succession of classes over any considerable time. At one period, there will go out of college halls a group of men who leave their marks upon the public life of their era; another period will produce great scholars; at still other times, men who come to high distinction in their vocational fields or men destined to make their lives significant in altruistic service go forth. The striking facts, meanwhile, are the extent to which men who attain to greatness in achievement or in service are shown to have been bunched within given years or sequences of years and the comparatively barren intervals which elapse between the appearance of one group and another.

Inasmuch as there can be no ready assumption that men of one college generation are radically different in natural attainments or in mental capacities or in spiritual qualifications from those of generations immediately succeeding, we must assume the difference to be in the spirit of the respective times or more likely in the attitudes taken and the influence wrought by associations of kindred minds at given periods.

The same type of influence can be traced frequently as well in the outside world. What produced the hardy group of English adventurers who used to gather in the coffee house in Exeter and whose achievements made England the greatest sea power the world has ever known? What, in Lincoln, Nebraska, worked on the minds of the extraordinary coterie of men which met for a time together there and then went out to assume major parts in the world's affairs? What aroused the interest in literary effort which produced the generation of writers we call the Indiana school? Such examples can be multiplied.

THE ATTITUDE OF DISILLUSIONMENT

In discussion of this subject with some number of men it seems possible to set up one hypothesis, namely, that most great achievement springs from human minds which have acquired the habit of courageous response to the challenge of contemporary life. These have, or cultivate, the mental and spiritual attitudes which create a mood of hope and optimism. These respond to the stimuli of the accomplishments of civilization rather than allow themselves cynically to hold its failures to be irreparable defects.

Now, while complacent acceptance of opinion that all is right with the world and unquestioning faith in belief of others would be as undesirable as it would be unintelligent, nevertheless, optimism and buoyancy are qualities which are natural attributes of youth. When youth abandons these, it abandons the vital sources of power to make itself an active factor rather than a passive one in the life of its generation. Moreover, when it largely forgoes its natural characteristics, it of necessity must strike a pose with all of the accompanying disadvantages of artificiality, which, at their best, lead to awkwardness and easily slip from that into absurdity.

The world suffered tragic adversity fifteen years ago and the agony endured for half a decade. Grief untold was planted in many a human breast. The world suffered dire calamity in the loss of countless numbers of potential leaders and many a youth of that time in greater or less degree had the spiritual reaction to it all that Erich Remarque has described. There should be no complaint against and there should be nothing but compassion for those who, having endured and suffered for the ambitions and mistakes of others, live in the murky gloom of disillusionment and cynicism. However, even among these who underwent the war, this group is a small minority.

The time has come, I think, to question the validity of the attitudinizing of that cult whose sufferings, if any, have been vicarious and whose claims to superior sensitiveness to the rest of mankind are as doubtful as their assumptions of superior intelligence.

The application of this all, for the present occasion, is to raise question with undergraduates of this college as to what motivations of the outside world they are to accept as influential upon themselves,—the constructive or the destructive.

ENTHUSIASM FOE LIFE PERSISTS

Let us give due attention to these facts! Civilization has shown a vital resiliency and a recuperative power within the past decade the existence of which could not have been suspected before. It has salvaged many values for a time lost and is well on its way to the creation of new ones. It is still far from perfect and labors under many a defect but it is free from many an ancient evil and it is rid of many a modern fallacy. All in all, men are more free than ever before to seek the truth and to accept governance of it in their own lives. More and more, despite sporadic instances that would seem to dispute the statement, the world at large desires to know truth. What more does the genuine intellectual need to give him inspiration and to breed reasonable optimism?

Least of all have the youth of America justification in these days to allow their enthusiasm for life to be dulled or to allow their aspirations for life to be circumscribed. Opportunities lie about us so abundantly that the only concern is for the wisdom we may have in selection of these. The machine age is freeing life of the necessity for sordid toil and giving rapidly increasing leisure and economic resources which, if we so will, may be made available for the spread of culture and the establishment of new standards of satisfaction for human existence. Our problem is not a paucity of resources but the intelligence to utilize the wealth of these to build ourselves up rather than to dissipate ourselves and to belittle ourselves in frivolities or in inconsequence.

After a somewhat careful scrutiny, extending over several years, of the pronouncements of undergraduates of colleges in this country, my conviction is very strong that genuineness calls for a new note to be sounded and one more natural to the instinctive spirit of youth. Otherwise, enthusiasm for life will remain dampened and the all-essential imagination of youth will become dulled and ours will be a generation wasted.

Let us consider if it is not possible to be serious without being solemn; if it is not possible to be determined without forgetting one's sense of humor; if it is not possible to become profound without being dull. Good nature does not have to be destructive of purposefulness. Poignancy is not a necessary concomitant of intelligent public concern.

In short, when the intelligently-planned and courageously-executed pioneer flight of a modest private citizen from New York to Paris can stir friendly emotions and create international good will toward the United States to an extent greater than provincial legislative attitudes can destroy; and when more completely than diplomacy could do it, a great people are rehabilitated in the world's interest and respect by appealing to the world's imagination through dramatic accomplishments such as those of a Bremen or a Graf Zeppelin, it would seem that the time had come to concede that dour rationalization is not all of life. It all suggests the interesting query whether a few evangelistic "Hallelujahs" and an occasional song to the general effect of "Oh, let us be joyful," might not be conducive to later accomplishment, as well as to present good cheer, of those who make up the great undergraduate constituency in higher education in the United States.

THE COLLEGE'S INCREASING PRESTIGE

Finally, and in this vein, a word as to the present status of the institution with which you have associated yourself, and other institutions of like character. The American college was in its origin an instrument of higher education devised to meet particular needs of a pioneer people. Consonant with this spirit in its foundation, it has evolved, developed, and diversified itself in accordance with the rapidly changing organization of society in America from one method to another and in conformity with one environment and another until the present time. It was fashioned largely at first, as would naturally have been the case, on the model of the English colleges. Later, it was greatly influenced by the ideals of German scholarship and the methods of German universities. Throughout its history, however, it has been sui generis, like the people whom it serves, and it has been characterized by elements of strength and weakness such as have characterized this people. So it is today!

Restricted oftentimes in the realization of its aspirations by fallacious conceptions of what constitutes democracy, it has retained its idealism; repressed frequently by forces which sought to make it their agent, it has retained its freedom; attacked persistently as radical, when it has declared its independence of conventionalists, and denounced as supine, when it has refused to ally itself with extremists, it has remained independent. Operating in recent years between barrages of criticism from within and uncomprehending complaint from without, its strength has yet grown and the breadth of its appeal has constantly widened.

Today, the American college has prestige, influence, intellectual vitality and consequent potentialities far beyond those which have been evident in any former time. Moreover, it has increasingly the openness of mind, the sense of responsibility, and the determination to utilize its opportunities and to render its desirable service. Its major obligation still is to human society and its principal solicitude is that civilization continuingly shall benefit from the absorption into itself of individuals who are better and wiser and more competent and more cooperative than they would otherwise have been. Specifically, this is today the principal concern of Dartmouth College.

To the Senior in the final stages of his apprenticeship to educational ideals; to the Junior entering upon enlarging opportunities within the educational method of the College; to the Sophomore with his advancement into greater understanding of College purposes; and to the Freshman on the threshold of a four-year adventure that, rightly used, may become one of the happiest experiences of his life;—to each apart and to all together this historic college extends the affectionate welcome of a fostering mother and bespeaks her high hopes in you who constitute a new generation of sons in whose abilities she has confidence but whose capabilities remain to be revealed.

SKY LINE From Great Bear Cabin of Dartmouth Outing Club

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

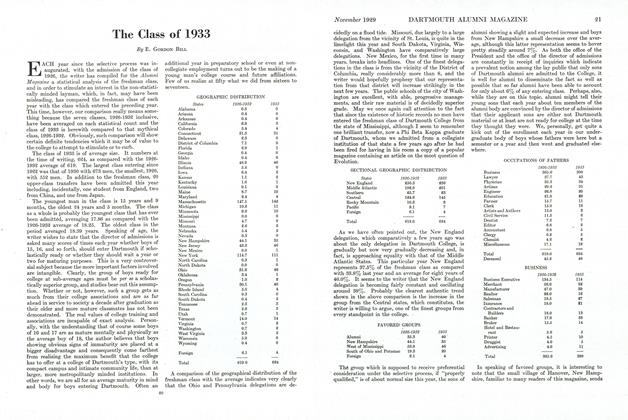

ArticleThe Class of 1933

November 1929 By E. Gordon Bill -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1929 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

November 1929 By Frederick W. Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1909

November 1929 By Robert J. Holmes -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1919

November 1929 By James Corless Davis

Article

-

Article

ArticleFACULTY ACTIVITIES

November, 1915 -

Article

ArticleHer Business is in the Bag

December 1987 -

Article

ArticleHot Shots

April 1995 -

Article

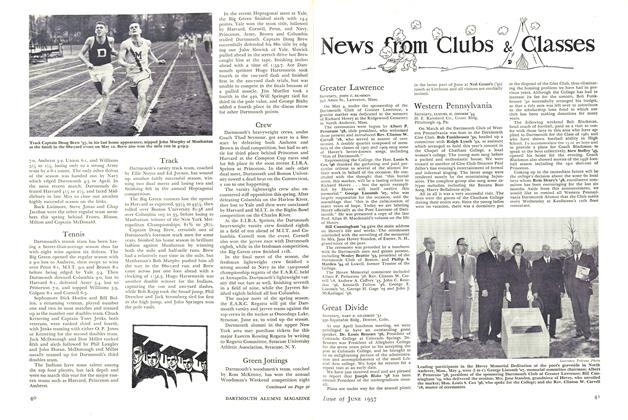

ArticleTrack

June 1957 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticlePrep For Success

Jan/Feb 1981 By Marsha Belford '78 -

Article

ArticleANNUAL REPORT OF THE CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATION

August 1917 By WILLIAM J. TUCKER.