For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

ANOTHER YEAR BEGINS

THE years go quickly. It seems but yesterday that Dartmouth College was celebrating its sesquicentennial, yet it is now entering its 161 st year and is heading for its 159 th Commencement.

This is not the place to go into any historical panegyric, yet it must always be a source of pardonable pride to every alumnus of the College to reflect on the past 160 years of honorable record and to see in the Dartmouth of today every augury for a future equally honorable, equally useful, and far more comprehensive in scope than any of the founders dreamed. Indeed, the present College surpasses, in pretty nearly every way, the most sanguine expectations of those who came long after the time of Eleazar Wheelock. It is quite improbable that Dr. Tucker, when he retired from the presidency in 1909, had the remotest idea of what he was destined to live to see as the fruit of his own labors.

The extent to which the continuance of this noble history depends on the alumni of Dartmouth, it is desirable every alumnus should recognize—as presumably most of us already do. The function of the alumni in our case is much better developed than in most similar institutions and comes closer to being an integral, vital, driving force. So long as that spirit endures, Dartmouth has nothing to fear. Among us one hears nothing of the common charge so often brought against college alumni that they are, on the whole, more of a nuisance to the college than anything else—far more of a liability than an asset—and are tolerated mainly because of their potentialities as a source of money in times of need. At Dartmouth, one has come to look to them for intelligent and cordial coooperation as a recognized and valued part of the college entity. The Dartmouth spirit is not a transitory enthusiasm, whipped up once or twice a year at formal dinners, or big football games. It is more like a going concern, operating often half consciously, but constantly, just the same.

With a view to making more clear than perhaps it would otherwise be to alumni of the most recent years, the vital force which Dartmouth's graduates have become in the regular conduct of the College, the Alumni Council has been attempting of late to summarize in convenient—and hopefully readable—form the chief points in which Dartmouth graduates make their useful contact with the administration. This—"when, as and if issued"—the MAGAZINE commends to the thoughtful perusal of every alumnus. It is above all desirable that the College be not dependent on a handful of what we like to call "professional alumni"—a few men almost too feverishly interested for comfort and likely to become something of a bore to those who lack their passion. What is wanted is a broader thing than thatthe sincere devotion and helpful personal interest of many thousand men. In a way, it is like the need of a country for a vast multitude of good citizens—citizens who take the obligations of their citizenship seriously day in and day out, rather than in the boastful spirit of the eagle-screaming patriot of the hustings.

Dartmouth has something over 12,000 living alumni, we believe, and the bulk of them belong to the more recent classes. These necessarily know the newer Dartmouth, rather than that older Dartmouth on which the new was built. To such, what now is may well seem a matter of course. To those who remember the day of smaller things, what has come to pass seems far more of a miracle, and it is possible the longer relationship tends to promote a more intimate feeling in consequence. The thing aimed at now is to weld this citizenship into a steadily and dependably useful massor rather to insure its remaining such, for such it already is.

As was said at starting, Dartmouth now enters on its 161 st year. It does so with the cordial God-speed of every graduate'. The past is secure. The future may be yet more creditable. It will be at all events what we, the active alumni members of the Dartmouth entity, see fit to make it.

WISE WORDS TO FRESHMEN

FOR a guess, the salutatory remarks which the president of a college customarily makes to an entering class have more practical results than attend the delivery of an eloquent baccalaureate sermon to departing seniors. Freshmen on the threshold of a college are likely to be in a more receptive moodcertainly more in awe of their surroundings and anxious for guidance therein.

President Hopkins, always felicitous on such occasions, devoted his opening address this year to what he aptly described as "Orientation" with a view to acquainting newcomers to the scene with certain views pertaining to the College, its general aims, and in an especial manner to its attitude toward undergraduate opinion. The best possible way of obtaining an idea of this address, of course, is to turn to it and read it- a course which will amply repay the reader. But it may be well here to touch briefly on certain salient facts, by way of comment.

The fact that these young men constituting the freshman class have been chosen out of a very large field of applicants is evidence that they have been estimated to be the most worthy of admission to partake of the opportunity which Dartmouth offers. Circumstances compel the College to turn away many even who seem well qualified to get in—simply because there is not room. Those who do secure admission have a reputation to sustain. They have succeeded in obtaining something desired by many other young men in vain; and they have succeeded because after a careful investigation it seemed to those having the watch and ward that they would make the best use of their privileges. "A college gives no man an education," said the President, "but it gives to all men who associate themselves with it the opportunity to become educated. The major emphasis is on teaching men how to seek for knowledge rather than on stating what knowledge is." What will be done with the chance thus accorded to 500 young men out of some 1,200 who sought membership in Dartmouth is largely up to the young men themselves. The College lays before them all its facilities. It cannot compel them to make the fullest use thereof.

Moreover, it has the guise of a distinct bargain. Last year the College offered to its students educational opportunities, the cost of which, exclusive of any construction charges, was $1,633,000. The students re- ceiving this education paid only $809,000—a trifle less than half the actual cost of what was given them—this, despite a tuition fee already raised beyond that of most similar colleges. It couldn't be done if it were not for the steadfast support of alumni, 5,683 of whom cheerfully contributed out of such means as each possessed, a sum of money approaching $130,000 to extinguish the deficit remaining after all other resources, including the income from meagre endowment funds, had been exhausted. That sort of thing would not be done year after year, as it has been and continues to be, were there not something strong and compelling as a reason, which one describes in the rather trite phrase, "the Dartmouth spirit." It is well enough to acquaint these newcomers to our fellowship with the existence of that spirit and to point out its vital worth to themselves.

Perhaps the most pertinent of all the remarks were those relating to the mutual attitude of College and undergraduates. Undergraduate opinion is usually critical, and frequently is justly so. No college has been more ready than Dartmouth to consult that opinion and act on it where it appeared to be well justified. None the less, President Hopkins reminded his auditors that the wise college "will be far more solicitous to provide the man the undergraduate is to become with what he will hold (in his greater maturity) to have been valuable to him, than to provide what a nebulous undergraduate sentiment, which periodically vacillates according to cycles, appears to desire at any given time." In other words, there is no policy of "giving the people what they think they want" just because at a given moment they happen to believe they want it. There has to be more to it than that—something that inspires the idea that when these undergraduates are 50 years or so out of college, they will still think this thing to have been of value to them. "What seems best to mankind as a whole," went on the President, "cannot be forgotten or ignored in college management for the specious satisfaction of conforming to an ephemeral undergraduate opinion, or the desires of self-centered individuals."

Dartmouth seeks to bestow opportunities to obtain a "liberal" education—that is, a free search for truth unhampered by narrowing limitations to fields of activity. "Its primary concern is not with what men shall do, but with what men shall be." It wishes to stimulate minds to activity. Now and again one has resorted to the simile of the master-key—the key which may be used to open all locks, as distinguished frOm that which will open a single lock only. The liberal education ought, we believe, to precede purely technical education, empowering men not only to approach specialized study with a better-equipped faculty of mind, but also inspiring them with a better capacity to make use of their leisure when attained.

Something of especial value was said toward the close, which was to the general effect that one could be serious without being solemn—and particularly, one might add, without being cynical. There has been a vogue in recent years, especially among college men, for cynicism as a pose, as if the ordinary emotions and feelings which young men have always felt were something to be ashamed of and suppress. One is moved to echo the wish of the President for "a few evangelistic Hallelujahs and an occasional song to the general effect of 'O Let Us Be Joyful,'" from the ranks of the more sober-sided and more acidly critical in our midst. Such things can be overdone by the thoughtless, of course; but the point is, there is more room for them in the equipment of the thoughtful than is generally utilized.

NIL ADMIRARE

BUT gray-haired professors need no longer worry about "overemphasis," for, we understand, a reaction is already underway. Reports from Hanover, N. H., have it that it is not now considered heretical for undergraduates to play golf or take a hiking trip even while the Big Green team is engaged in so-called mortal combat. Harvard and Yale both went without rallies before their game last year, and the skies did not fall—somewhat to the disappointment of a few of their alumni. . . .

Call it intelligence or degeneracy, but you can't deny that there is what sociologists call "a distinct trend."— Boston Herald.

The fashionable thing recently among undergraduates in American colleges has seemed to be a cynical pose. One has been led to be rather ashamed to reveal any spontaneous emotion, by the inculcation of a general belief that to do so is somehow unworthy, demoded, out of style. One should be immune to the common enthusiasms, which are held to be the mark of the Babbitts of this world, and cultivate an attitude of indifference toward what ordinary folk hold to be things to admire. This has flowered forth in curious ways, varying from a reaction against whipped-up emotionalism at pre-big-game mass meetings, to a declaration in favor of abolishing some time-honored institutions such as the national Greek letter fraterni- ties and even intercollegiate sport itself.

Now the great trouble with that is that it isn't genuine. It is in itself whipped-up and artificial. It isn't arrived at naturally, but by deliberate design in the hope and intention of being "different" from the common run. Often it seems to be a sort of immature aping of the supercilious "Intelligentsia," who are so much with us, late and soon. No college has escaped it. To be sure, it has by no means produced all the results declared by the critical few to be so desirable, but it has had an effect on the colleges—possibly transitory, but for the moment real. One has moments of wishing that these hypercritical young men might be jostled suddenly out of their attitude of superiority by some intensely moving experience, which should suffice to reveal them to be genuine human beings after all, with a capacity for the spontaneous enjoyment of something that ordinary mortals enjoy—even if the reaction of the next moment might be one of shame for having so far forgotten one's pose as to emit a wild cheer of exultation.

The passion for being different is understandable, and often justifiable, but it seems hardly the sort of thing to erect into a substitute for worship, or make the guiding principle of life. There is small intrinsic virtue in merely being different from other people of one's own day, even if there is equally little virtue in being precisely like every one else. It may be well to revive Aristotle's famous theory that it is bad to have too much of anything—whether it be standardized or unstandardized conduct.

A SUCCESSOR FOR EDISON?

THE highly interesting examination conducted under the direction of Mr. Edison last summer in order to discover a worthy successor to our most brilliant and useful inventive genius may or may not produce the successor. At least it revealed one promising lad who answered more -questions to the satisfaction of the examiners than any of the others, and of course the newspapers have been nominating him the "smartest boy in the country"—which is in itself a considerable test. The real examination of this successful aspirant is probably yet to come.

So much was said and printed concerning the test at the time it was made that presumably nearly every one has some idea of the scope of the inquiry, which was distinctly varied in its character. It included a number of straight scientific questions, which boys competent to enter a technical school of the higher grade could in most cases handle without much trouble. The more important part, one suspects, was that devoted to searching problems of ethics and tests of what may be called common sense, interspersed through the paper. Mr. Edison moved in a mysterious way, but on the whole a wise one. The trouble with most examinations is that they show little beyond a power to obtain marks. This one went into the character of the examinee and it is probably that this element proved the decisive one.

It may be doubted that any such test can guarantee a successor to Mr. Edison, however, because men of his extraordinary ability derive from something transcending book knowledge. To be an Edison requires a gift which is vouchsafed to few. From among a lot of boys chosen from the several states, one was found who appeared to show the most all-around promise, and it is to be hoped that such a lad will develop into a useful follower in Mr. Edison's footsteps. Nevertheless, an examination, even of this ingenious character, cannot go very far. It is, however, no doubt the best available instrument for making a beginning, imperfect though it must be.

THE ALUMNI COLLEGE

DISCUSSION in various contemporary publications devoted to the interests of college alumni have occupied some litte space in recent months, concerning the best method of projecting the usefulness of the colleges among their graduates—most of these looking toward a sort of university extension to be enjoyed by such alumni as may retain sufficient intellectual interest to warrant their taking a little trouble to cultivate the same. It now appears that a slightly different method has been adopted, and with initial success, at Lafayette, where a brief session of a single week last June was thrown open to alumni on invitation of President Lewis. About 70 graduates availed themselves of the opportunity and are said to have come away highly enthusiastic for a repetition of the experiment next summer.

The plan appears to have included lectures by the leading professors in each department, these speaking informally of the progress made in their respective fields of study, followed by discussion at what are now fashionably called "round tables." These lectures covered the drama, the Old Testament, educational theories, chemistry, electrical engineering, political science, economics, literature—and football coaching. The afternoons were devoted to recreational out-door sports. This is a brief and sketchy sort of alumni college, but it probably works out better from the practical standpoint than would a sustained all-the- year effort to include a number of alumni in the scope of continuous college study.

The fact, of course, is that the average man after graduation is too busy to devote much time to continuing his studies, either by correspondence or by occasional visits to some extension school. It might enhance intelligent interest in the colleges if things were otherwise, but they are not and probably never will be for more than a very few leisured men. As a result, the interest in college affairs is apt to centre on the recreational side—the fortunes of the alma mater's athletic teams—to the grief of faculties and presidents who feel that sports are somewhat over-stressed in the graduates' case. Hence the common desire to revive intellectual along with athletic interest, and the yearning toward the alumni college idea. Possibly Lafayette has hit on the most workable form thereof.

THE HOCKEY RINK

IT is a gratifying announcement that has recently been made of the gift of a covered hockey rink by an anonymous but generous donor. For years this subject has been agitated by hockey enthusiasts and on more than one occasion it has seemed as though plans were actually going to materialize. Now the hopes have become a reality and construction is already under way to make possible the use of the rink during the coming winter. Details of the plan will be found elsewhere in this issue.

It will no longer be necessary for the large crowds that attend the Carnival game to sit in biting winds or driving blizzards. The uncertain New Hampshire winters may do their worst without affecting the surface of the ice and assurance may be had that games will be played as scheduled. Occum Pond will doubtless still serve as the centre of recreational skating and informal hockey games but the new rink brings still nearer to completion the plans of the Athletic Council for a completely equipped plant for organized athletics centering around the gymnasium.

Hockey has long been one of the most popular sports at Dartmouth. Despite handicaps of poor ice a creditable team has always been developed and occasionally an outstanding one. Now that the largest obstacle to this development has been removed the sport should go forward to even greater success. The unknown donor has earned the gratitude of alumni as well as of the undergraduate college by his timely gift.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

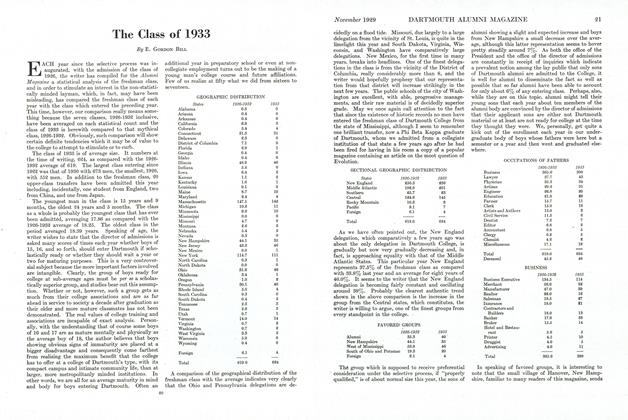

ArticleThe Class of 1933

November 1929 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

Article"ORIENTATION:" The Opening Address of Dartmouth's 161st Year

November 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1929 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

November 1929 By Frederick W. Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1909

November 1929 By Robert J. Holmes -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1919

November 1929 By James Corless Davis

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

FEBRUARY 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MARCH 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

January, 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

OCTOBER 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

DECEMBER 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

JANUARY 1932