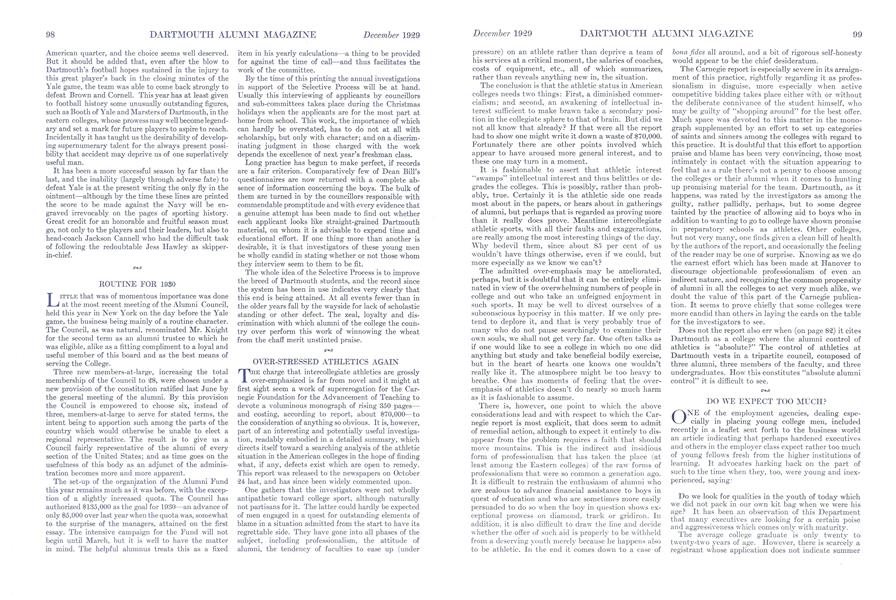

The charge that intercollegiate athletics are grossly over-emphasized is far from novel and it might at first sight seem a work of supererogation for the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching to devote a voluminous monograph of rising 350 pagesand costing, according to report, about $70,000—to the consideration of anything so obvious. It is, however, part of an interesting and potentially useful investigation, readably embodied in a detailed summary, which directs itself toward a searching analysis of the athletic situation in the American colleges in the hope of finding what, if any, defects exist which are open to remedy. This report was released to the newspapers on October 24 last, and has since been widely commented upon.

One gathers that the investigators were not wholly antipathetic toward college sport, although naturally not partisans for it. The latter could hardly be expected of men engaged in a quest for outstanding elements of blame in a situation admitted from the start to have its regrettable side. They have gone into all phases of the subject, including professionalism, the attitude of alumni, the tendency of faculties to ease up (under pressure) on an athlete rather than deprive a team of his services at a critical moment, the salaries of coaches, costs of equipment, etc., all of which summarizes, rather than reveals anything new in, the situation.

The conclusion is that the athletic status in American colleges needs two things: First, a diminished commercialism; and second, an awakening of intellectual interest sufficient to make brawn take a secondary position in the collegiate sphere to that of brain. But did we not all know that already? If that were all the report had to show one might write it down a waste of $70,000. Fortunately there are other points involved which appear to have aroused more general interest, and to these one may turn in a moment.

It is fashionable to assert that athletic interest "swamps" intellectual interest and thus belittles or degrades the colleges. This is possibly, rather than probably, true. Certainly it is the athletic side one reads most about in the papers, or hears about in gatherings of alumni, but perhaps that is regarded as proving more than it really does prove. Meantime intercollegiate athletic sports, with all their faults and exaggerations, are really among the most interesting things of the day. Why bedevil them, since about 85 per cent of us wouldn't have things otherwise, even if we could, but more especially as we know we can't?

The admitted over-emphasis may be ameliorated, perhaps, but it is doubtful that it can be entirely eliminated in view of the overwhelming numbers of people in college and out who take an unfeigned enjoyment in such sports. It may be well to divest ourselves of a subconscious hypocrisy in this matter. If we only pretend to deplore it, and that is very probably true of many who do not pause searchingly to examine their own souls, we shall not get very far. One often talks as if one would like to see a college in which no one did anything but study and take beneficial bodily exercise, but in the heart of hearts one knows one wouldn't really like it. The atmosphere might be too heavy to breathe. One has moments of feeling that the overemphasis of athletics doesn't do nearly so much harm as it is fashionable to assume.

There is, however, one point to which the above considerations lead and with respect to which the Carnegie report is most explicit, that does seem to admit of remedial action, although to expect it entirely to disappear from the problem requires a faith that should move mountains. This is the indirect and insidious form of professionalism that has taken the place (at least among the Eastern colleges) of the raw forms of professionalism that were so common a generation ago. It is difficult to restrain the enthusiasm of alumni who are zealous to advance financial assistance to boys in quest of education and who are sometimes more easily persuaded to do so when the boy in question shows exceptional prowess on diamond, track or gridiron. In addition, it is also difficult to draw the line and decide whether the offer of such aid is properly to be withheld from a deserving youth merely because he happens also to be athletic. In the end it comes down to a case of bona fides all around, and a bit of rigorous self-honesty would appear to be the chief desideratum.

The Carnegie report is especially severe in its arraignment of this practice, rightfully regarding it as professionalism in disguise, more especially when active competitive bidding takes place either with or without the deliberate connivance of the student himself, who may be guilty of "shopping around" for the best offer. Much space was devoted to this matter in the monograph supplemented by an effort to set up categories of saints and sinners among the colleges with regard to this practice. It is doubtful that this effort to apportion praise and blame has been very convincing, those most intimately in contact with the situation appearing to feel that as a rule there's not a penny to choose among the colleges or their alumni when it comes to hunting up promising material for the team. Dartmouth, as it happens, was rated by the investigators as among the guilty, rather pallidly, perhaps, but to some degree tainted by the practice of allowing aid to boys who in addition to wanting to go to college have shown promise in preparatory schools as athletes. Other colleges, but not very many, one finds given a clean bill of health by the authors of the report, and occasionally the feeling of the reader may be one of surprise. Knowing as we do the earnest effort which has been made at Hanover to discourage objectionable professionalism of even an indirect nature, and recognizing the common propensity of alumni in all the colleges to act very much alike, we doubt the value of this part of the Carnegie publication. It seems to prove chiefly that some colleges were more candid than others in laying the cards on the table for the investigators to see.

Does not the report also err when (on page 82) it cites Dartmouth as a college where the alumni control of athletics is "absolute?" The control of athletics at Dartmouth vests in a tripartite council, composed of three alumni, three members of the faculty, and three undergraduates. How this constitutes "absolute alumni control" it is difficult to see.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

December 1929 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

ArticleAlumni Associations

December 1929 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meets in New York

December 1929 -

Article

ArticleCarnegie Report

December 1929 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Indians

December 1929 By Eric P. Kelly -

Sports

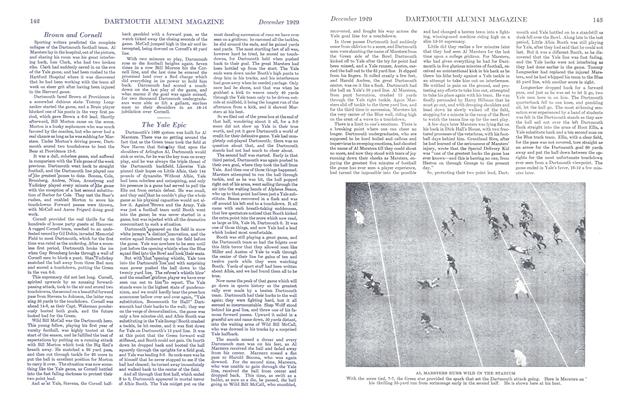

SportsThe Yale Epic

December 1929 By Phil Sherman