You don't have to be Jewish to love Jewish fiction.

WHat DO PHILIP ROTH, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Nadine Gordimer, Grace Paley, Saul Bellow, E.L. Doctorow, Elie Weisel, Henry Roth, and Bernard Malamud have in common? On the surface, that question might not be very difficult to answer. But whether or not the answer goes deeper than the fact that they are great writers, who also happen to be Jewish, is subject for debate, according to novelist Alan Lelchuk, who teaches a course on contemporary Jewish fiction.

Just because some of the best writers of the past 50 years are Jewish doesn't mean that their subject matter or style can be labeled as "Jewish," says Lelchuk. "Great writers don't belong to a school. They're individuals," he insists. The authors he includes in his course, which is part of the the College's two-year-old Jewish Studies Program, grapple with universally human issues—such as morality, suffering, identity, and a yearning for a sense of belonging. "Isaac Bashevis Singer explores the power of innocence and suffering in 'Gimpel the Fool,' while in The Assistant it is clear how strongly Bernard Malamud believes in the necessity of intimacy and responsibility of all human beings," says Lelchuk, "Grace Paley is poignantly funny, while Philip Roth has a fiercely wild type of humor. E.L. Doctorow's Book of Daniel deals with Jewish radicalism in history, as does Singer's Satan inGoray. Roth and Saul Bellow could both be described as aggressive and intellectual in many of their works, but radical in style and voice." The characters are in situations of crisis—domestic, public, intellectual, or historical. "They are all humanly involved, humanly entangled," says Lelchuk, "and that gives their novels firm grounding. They are novels about experience, not wordgames or theories."

Some authors also explore a more specific set of Jewish issues, including Jewish identity, the role of the Jewish intellectual, Jewish radicalism in history, and the Holocaust. All of the Holocaust writers Lelchuk chooses for his course—lda Fink, a Polish writer who now lives in Jerusalem; Aharon Applefeld, also living in Jerusalem; Borowski, a Pole who committed suicide in about 19 51; and Elie Weisel, who is most famous for Night, his moving account of being a boy during the Holocaust—lived through the Holocaust and were personally and powerfully seared by it. Their writing shows this in an interesting way—most take a very low-key, muted, deliberately anti-sensational approach. Lelchuk believes that only people who Lived through the Holocaust can authentically portray it. "It may be hovering in the consciousness of some characters in Bellow's or Roth's work, in some way—like it is in the Jewish consciousness—but the Holocaust is too big an historical fact, too loaded with nightmarish reality, to go any closer to it with a fictional imagination."

During the first part of this century Jewish writers worked at the margins of American literature. It wasn't until the late fifties that a serious Jewish author made it to the inside track of the American literary scene. Saul Bellow won his first of several National Book Awards for Augie March. Bellow's prose style, which Lelchuk describes as "extremely rich in its mingling of Yiddish phrasing and inflection, American rhythms, and European philosophical meanderings in the midst of concrete details," was hard for Americans at first. But Bellow's National Book Award opened readers to Roth, Malamud, and Singer. (Bellow's translation of Singer's "Gimpel the Fool" gave Americans their first taste of Singer's amazing gift for storytelling.) Today, says Lelchuk, Jewish writing is completely at home in America. "Now we have writers who are writing about the grand American experience—immigrant and post-immigrant—with the style and vision and relaxed confidence of people who know their material and are writing about it from the inside, not from the outside looking in."

Jewish perspectives on life have caught on in American popular culture, too. (Just look at the national obsession with JerrySeinfeld.) Even Yiddish has gone so mainstream that during the Presidential impeachment trials, the words "shlep" and "chutzpah" echoed in both the Senate and House. "The Jewish sensibility," says Lelchuk, "tends to be ironic, skeptical, funny, cosmopolitan, willing to embrace all kinds of possibilities and uncertainties, embracing the power of the other, a deep sense of restlessness—with your own stake in things, your own place, your own personality. And because of this, you get an open attitude toward American reality and an in-depth exploration of all the wonders and mysteries of the country."

Among contemporary Jews who write about American life is Lelchuk himself. His 1973 debut novel, American Mischief about campus turbulence in the sixties, gained notoriety when, as a Book-of-the-Month selection, it cost the club thousands of members who quit because they objected to the book's themes and obscenities. "The judges had to write an explanation saying why they had chosen my book, plus they ran an interview with me to show how civilized I really was," says Lelchuk proudly. Playingthe Game, about Ivy League basketball, is set at Dartmouth. His next book Zijf: ALife?, "a sad comedy about the life of a Jewish writer," is coming out next year.

Lelchuk works the other end of publishing, too. Frustrated with the bestsellers-only mentality of American publishing, he and three partners established Steerforth Press in South Royalton, Vermont, to publish "good books of any sort." Lelchuk wants to redress a growing problem in Jewish literature: many books, including the classics, are out of print. "Brilliant voices are in danger of being lost altogether, buried in obscurity," he says. Steerforth plans to establish a Modern Jewish Library to reprint books that shouldn't be forgotten.

Jewish writing no longer sits at the margins of American literature.

TAMAR SCHREIBMAN is a writer living inBrooklyn, New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Research Question

October 1999 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureA Poet (Visiting)

October 1999 By Sarah Messer -

Feature

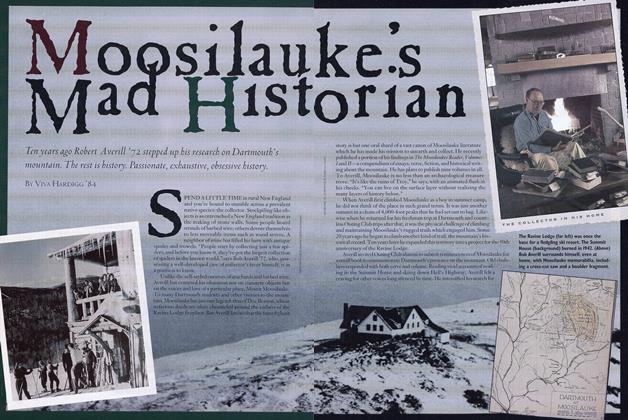

FeatureMoosilauke's Mad Historian

October 1999 By Viva Hardigg '84 -

Article

ArticleTeamwork

October 1999 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleArtists 22, Philistines 14

October 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

October 1999 By Leslie A. Davis Dahl, John MacManus, Shelley L. Nadel