By C. H. Forsyth. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1928. (200 pages.)

For the past decade authors have been publishing text books for a college course in the mathematical theories involved in problems concerning interest, annuities, capitalization, depreciation, bonds, and life insurance. The latest of such books, Professor Forsyth's Finance, makes several improvements over its predecessors.

In this book are not found the complicated symbols and notation which some have employed. By treating life insurance by the method of Euler, a chapter on probability is made unnecessary. And the theory throughout the book progresses happily without involved formulas. No other of its contemporaries contains a chapter on fire insurance. More positively, the underlying principle whether in presenting a theory, developing a method or a formula, or in teaching the student to analyze and solve problems, is the use of equations of value. Another dstinctive advance is the use of the conversion period instead of the year, as the unit of time. In most of the book mathematics is the tool and not the product—the object seems to be,not mathematics, but insight into and handling of relations of money and time.

And so the book is teachable, although some of the derivations are departures from the conventional ways. It is meant for a semester course, and "no 'mathematical preparation excepting that of a good preparatory school course in mathematics (including logarithms and progressions) is absolutely necessary; but a year of freshman mathematics in college is, at least indirectly, helpful. However, there are topics (e.g., pages 165-170) which the average student will grasp more readily if at all, if the instructor is not just a clerk of the course. The style is unpretentious. There are sections in which statements more explicit would perhaps achieve the object with less confusion. There are typographical errors, even in the tables, but this is not a review of errata.

The exercises usually are satisfactory and graded in difficulty. There are few answers printed. Frequently "fundamental problems" are given throughout the book. These elaborate formulas already derived or involve the proving of less used formulas. Each of the ten chapters ends with a list of additional exercises, almost a hundred in toto. The volume contains twenty-five pages of tables which are sufficiently extensive for the working of any of the exercises, although the logarithms (four-place) are too inadequate to be of much assistance in the computations.

The material for the book has been obtained from many sources (although there is hardly a reference), but it is well unified. Moreover, the text is not an experiment but has been tried out in mimeograph form in the classroom by several instructors. The material is suited not only to the student in the college of commerce and finance, but is valuable to the undergraduate in a college of liberal arts or in a technical school. The book should win friends in classes where it is adopted, because of its minimizing the number of formulae and emphasizing the analysis of problems.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

April 1929 By Truman T. Metzel, "Charlie Chadbourne" -

Article

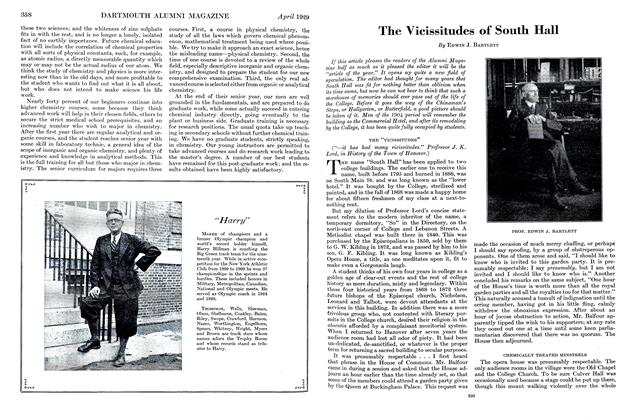

ArticleThe Vicissitudes of South Hall

April 1929 By Edwin J. Bartlett -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

April 1929 -

Article

ArticleFrench Life at Dartmouth

April 1929 By Howard F. Dunham -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

April 1929 By Louis P. Benezet -

Article

Article"The Dartmouth," An Explanation

April 1929 By W. L. Scott, Editor

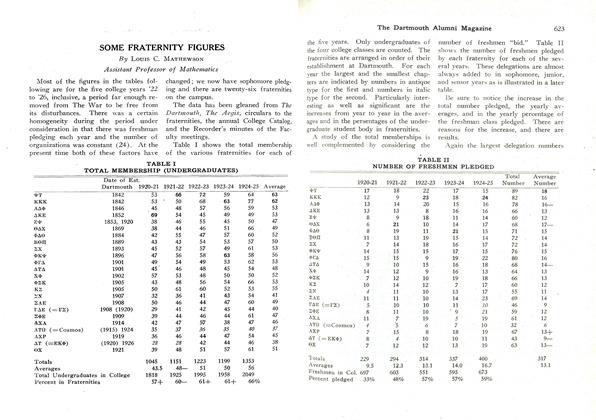

Louis C. Mathewson

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

April, 1915 -

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

MAY 1932 -

Books

BooksA WOMAN'S BEST YEARS

June 1935 By C. N. Allen '24 -

Books

BooksTHE WAY OF PHILOSOPHY.

June 1954 By HUGO A. BEDAU -

Books

BooksGREAT SOUL; THE GROWTH OF GANDHI

July 1949 By Philip Wheelwright -

Books

BooksA Student's Philosophy of Religion

June, 1922 By W. H. WOOD