For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

THE LIQUOR PROBLEM

THE liquor problem in the colleges is probably not very different from the liquor problem outside. A thing which was once legal has been prohibited by law; and human nature is so perversely constituted that in many cases a prohibition operates as an inducement to break the rules. It isn't much more true in the schools and colleges than it is outside; although the natural circumstances of massed youth and a juvenile eagerness to emulate the conduct of older people, coupled with the traditional propensity of all students to defy regulations of any and every sort when a special point is made of them, doubtless tends to localize and intensify the problem. But there always was a liquor problem in the colleges; and the phases of it which have been added since the passage of the Volstead law are very largely the same that exist everywhere else.

Enforcement of the prohibitory law is notoriously difficult everywhere, save in places where virtually all the citizens are in sincere favor of its enforcement. That isn't true in places enough to make the result very gratifying. It isn't true in most of the colleges, any more than it is true in most of the adult communities. What probably focuses the public attention to so great a degree on the colleges is the greater ease of observing the effects, thus producing a mistaken idea that the colleges afford a special instance. It is doubtful that they do so. As at present constituted, they afford a much broader cross-section of American society than they ever have done before, with all the advantages and disadvantages which that implies.

College authorities differ now and then as to whether or not the effect of the prohibitory law has helped or made worse the problem as it existed in prior years. The experiment is too young yet, one fears, to permit its effects to be assessed with a wholly dispassionate candor, whether in college or outside. No one as yet appears to be quite ready to face facts, whether for or against the 18th amendment, arid until a more openminded attitude on both sides is possible it seems futile to debate. Those who insist that more young people drink now than used to drink are offset by those who insist that drinking is much less prevalent than it was 30 years ago. The situation, however, is by no means confined to educational circles and the day for a genuinely impartial arbitrament of the issue seems remote. The immediate point sought to be made here is only that the colleges afford no peculiar and isolated problem. The problem is well nigh universal, and the disabilities attending its solution are universal also.

TUITION AND COST

ONE of the frequently heard queries in the various meetings this winter concerning the scope and purpose of the Alumni Fund has been, "How long are the colleges going to continue to sell education at a price below cost?" The only answer, probably, is "Always!" There may be no logic in it. There is some plausibility in saying that if a man is to get education at a price below its actual cost, he ought to get other useful things in the same helpful way. We do not ask a millionaire, because he can afford it, to pay more for a ticket from New York to Chicago than is paid by a person of comparatively little wealth. Each pays for what he gets, and if he cannot pay he doesn't get.

Still, you really cannot carry this parallel too far. It is a matter of genuine concern to the nation that its people be as widely educated as circumstances permit. It is further true that most of us, indirectly and belatedly, make good for what we didn't pay when we were students. It is even possible that, with the progress of thought on this line, definite methods will be devised to make this result a practical certainty by treating the discrepancy between tuition fees and actual cost as in the guise of a deferred payment. Meantime it is a practical necessity, especially for a growing college which has still much to do before it can afford to pause for breath, to maintain tuition at a level considerably below what the demonstrable costs would demand and rely on alumni funds and on the yield of crystallized endowments to make up the deficits.

Making the tuition nearly equal to the cost would have one seemingly salutary effect, of course, in that it would insure the application of only such as wanted education badly enough to pay for it. But are we quite sure that is what we want—in this country, at all events, and at this stage of its development? One can see the advantages; but it is conceivable that there are lurking disadvantages which may more than offset the good. There is the crying need of a general spread of appreciations, of ideals and of ethical standards. There is the danger of making the colleges "rich men's colleges." True, one may offset the augmented costs by scholarship aid—but that in itself might lead to invidious distinctions and bar some who would be deterred by false pride, although thus far it seems not to have done so. One ought to be very sure one is right before rushing to the position that there is nothing at all to be said for the existing practice, which charges less than the cost of operations and falls back on other resources to make up the slack.

WHAT'S WRONG?

WHAT'S WRONG with the colleges?" Something, no doubt, because there's something wrong with pretty nearly every human institution and always will be. Moreover the discussion of what's wrong with human institutions forms the favorite indoor sport of many thousand people. The colleges, the church, politics, society, youth, old age—all are the subjects of eager scrutiny with the idea of discovering what's amiss; and it is well enough that it is so, no doubt, because it would be a final negative upon progress if anything were once admitted to- be perfect. Nevertheless we have moments of wishing that not quite so many felt that the things that are wrong with this, that and the other institution are necessarily fatal.

Whatever is wrong with the colleges, it cannot be said to be a misguided sentiment on the part of those in charge of them that they are already perfect. None seems keener for the discovery of defects than the average college don. All sorts of new ideas have been suggested and tried within the past dozen years, and the end is not yet. Sometimes the result has been to promote a vague feeling that the colleges have had very little the matter with them at the start, compared with what has come to pass since; but out of such strivings and experiments is bound to come at least whatever progress we are capable of making.

The colleges have had to face a very marked change in their problem since their functions have been so greatly amplified. We must remember that hundreds go to college now who never would have dreamed of going 40 years ago. The task of the modern college is complicated by the enormous change in the constituency resulting from the educational passion now animating the people of the country—if it can be called that. Once on, a time collegiate education was reserved for the very few. It is now sought by the very many. Colleges that for a century had gone on, year after year, graduating just about the same size of class every June with just about the same general mental equipment, now have to deal with a student body which has quadrupled or quintupled within a decade. The old-style college won't serve. The new one hasn't got shaken down. Something's wrong, maybe—but nothing vital. The worst thing that could be said would be that the colleges hadn't visualized their own need for change; but that certainly cannot be said, in view of the experimentation now going on so eagerly all over the map.

If one were to venture a bit of dogmatism it would be that there isn't half so much the matter with the colleges, nor half so much wrong with them, as these voluble critics apparently have dared to hope. Considering the violent changes wrought by the recent years, as a result of which higher education has to be purveyed for the multitude instead of for a chosen few, the colleges do pretty well. They can and will do better, of course, but it isn't a process that can be forced with wisdom. Trying to speed up an educational millennium may actually do more harm than good.

BEING COLLEGIATE

THE DEAN of George Washington University appears to have started something within the past few weeks by directing to his brother deans in various parts of the United States a questionnaire concerning their ideas of what constitutes being "collegiate" in the understanding of modern students, the implication being that "collegiatism" relates to the peculiar fads and foibles of the moment among the more extreme young men and women engaged in higher courses of study—-which fads and foibles are accepted by youth in general as characteristic of collegiate society. From the tenor of the questions, one gathers that a suspicion exists that certain oddities of dress and deportment are what make up collegiatism—such as wearing no garters, so that male socks slump down over the shoes; going without a hat in public; affecting wrinkled apparel; eschewing neckwear; revealing a predilection for "necking" (the modern word for what has successively figured in college vernacular as spooning, fussing, petting, at id om.) or a passion for bootlegged liquor, and what-not.

That it is important to devote much time to defining "collegiatism" at any given moment it is hard to believe. There is always some idiosyncrasy which passes for collegiatism, and always will be. One with a retentive memory and 50 years of graduate life between himself and his student days will recall a time when it involved sporting sidewhiskers and affecting a "plug" hat. The gamut has been run backward and forward since then, varying from the extreme foppishness of the 1880's, when skin-tight trousers had their vogue, to the studious disorder in the dress which is the apparent fashion now. Who really cares?

To older eyes, whatever is affected as "collegiate" is pretty sure to look silly. One is urged to remember, however, that what one affected oneself when a student seemed egregious folly to the parents of that distant day. Who of us has not been berated in his time by sobersided old folk, who failed to see the sense, or maybe the propriety, of what we knew to be the fashionable conduct of our fellows? Your father probably spoke sneeringly of what you and other young men felt to be truly "collegiate"—and his father in turn very likely, if not certainly, cherished wholly similar feelings at a still more remote epoch.

The collegiatism of today unquestionably involves certain affectations, because affectation is of the essence. Collegiatism would not be collegiatism if it were not different, and rather strikingly different, from the conduct and attire of other people who are not collegiate. In due time—when those who are not of the college fold begin to ape too generally the antics and apparel of those who are—something else will be devised to stamp the college population. It is almost certain to smack of immaturity. Why not? It would be a miracle if it didn't do so. We mustn't expect too much of collegiatism. It is possible that we are by way of being too much worked up over it—as usually happens when older people express themselves over the goings-on of the young.

If we were a Dean, we believe we shouldn't worry too much about such things. Collegiatism is rather like chicken-pox—an infantile disease which it is well to have and get it over with. It will cease to be collegiatism in any given form when outsiders begin to copycat it. Whatever form it takes will seem superlatively idiotic to those no longer in college, and not at all so to those who are still in statu pupillaris. Scolding seldom suffices to awaken the exponents of any such cult to the views of their elders. One has to grow up.

HARVARD'S HOUSING EXPERIMENT!

THE interesting experiment projected at Harvard for the housing of all students-—or nearly all—in specially grouped buildings of dormitory character, with adjacent "halls" as the English would say for dining—will be thoughtfully observed. The extraordinary feature is that this major operation in collegiate economics will be financed by a noted alumnus of Yale, Mr. E. S. Harkness, whose participation is roughly estimated as likely to approach and possibly exceed $15,000,000.

One has learned from the newspapers—not invariably accurate in such matters—that the club life and social units on what used to be called the "Gold Coast" will not be interfered with at present by the inauguration of the new plan. It is further indicated that the group of Freshman dormitories on the north bank of the Charles river will probably cease to be occupied by freshmen, these being housed hereafter in the venerable buildings of the Yard, while the group of four handsome colonial structures now devoted to them will be incorporated in the new general group of "Houses" with additions in the same neighborhood—most notably in the area now made unsightly by a huge power-house and farther to the east along what motorists know as the Memorial Drive.

Just what will be the essential difference in the end is not yet clear. A set of new "Houses" more or less like collegiate units at Oxford seems likely to result, within the University, but not quite in the Oxford manner. At all events it is well to have Harvard move nearer the river. It ought probably to have been located nearer the river to begin with, but was not. No one foresaw the development with sufficient clearness to envisage the opportunities as they now present themselves. Those familiar with the district will no doubt hail with undisguised enthusiasm the disappearance of the power-house with its tall stacks and piles of coal, which was always a disfigurement and a reminder of the University's lost opportunities. If the opportunity was not seized at the outset, it is at least in the way of being regained.

Discussion of the plan itself would be dangerous in the absence of a far better understanding of the idea than any one seems at present to have outside the immediate parties to it. Cambridge is a very crowded city and expansions present problems of a very perplexing nature no doubt. It has been asserted and denied that Mr. Harkness first suggested the idea to Yale without awakening any interest in the University's managing circles. In any event Harvard has taken it up and the development will be watched with great interest everywhere. The outstanding fact is that with the new housing plan tending toward the north bank of the Charles, and with the Stadium and the Business School already occupying points of vantage on the southerly bank, Harvard is on the way toward a much more sightly scenic location than could be made to exist in the ancient site adjacent to Harvard Square.

UNSUSPECTED VIRTUES

THE unsuspected virtues of required chapel attendance are very well set forth in the paragraph about to be quoted from the Princeton Alumni Weekly, in an article devoted to considering what should be done to build up and make fertile a chapel service worthy of the magnificent new edifice lately dedicated at that university. The editors remark:

When alumni look back on their college course, after they have forgotten their callow complaints about "chapel," they realize that somehow in those great gatherings of the whole college a sense of corporate life has been unconsciously cultivated. The best spirit of the college is in some way connected with this practice of getting together. Thus it is that the alumni, taught by the perspective of years, become strong in the conviction that a college which neglects to foster such gatherings loses something peculiarly precious.

From casual observation it is a reasonable belief that the great majority of alumni—including some rather recent accessions to the fellowship and taking in every college where there has been a tradition of compulsory attendance on a brief daily religious exercise—sincerely regret the abandonment of such requirement wherever it has come about. In many instances—Dartmouth affords one—the change has been forced by the inadequacy of the space available, quite as surely as the feeling that students weren't getting very much "religion" out of being herded to churchly devotions every morning; but if our situation were to become like that at Princeton, with a splendid Gothic chapel crowning the Observatory hill as President Hopkins has sometimes suggested, we believe pretty nearly 90 out of every 100 alumni would be found urging a return to the old order.

It is well to remember that the word "religion" meant in its original form something that bound people together, and that is precisely what is hinted at in the Princeton comment quoted above. Men are forever changing their concept of God and of what is wellpleasing in God's sight. It isn't as common now as it was once to imagine God to be hoodwinked into favor toward man by sycophantic flattery such as no intelligent human being would allow to influence him. Religion, however, hasn't died and there is still need of God. As for the helpful effect of getting the whole college together once a day, that can hardly be gainsaid by any one; and giving it a religious guise need not militate against it to the point of undoing all the potential good.

That the restiveness of students against chapel requirements is "callow" and is due to the fact that the student lacks the perspective which future years will bring to him seems also truly said. Young men in a chapel to which the law forces them to repair are admittedly not all in a religious mood and many behave themselves unseemly—which in future years it is also fairly sure they will regret. But good seed falling on obdurate ground sometimes finds a chance lodgment; and while required attendance at chapel may seem to do little discernible good at the time, it certainly does no great harm and it involves the chance (indeed a virtual certainty) that men will be benefited in spite of themselves and their wandering attention.

It is idle, no doubt, to talk of compulsory chapel at Hanover until, like Princeton, we acquire a churchly building sufficient in size to contain all the students at once, and sufficiently inspiring in itself to constitute an irresistible uplifting of even the callous soul. We would merely stress the idea that, given such facilities, there is a virtue in requiring their universal use far beyond any mere formal lip-service toward a Supreme Being, such as too many imagine "religion" to be.

A COACHING PARTY TO WHITE RIVER JUNCTION This gala event took place in the early nineties. Note the four white palfries drawing the ladies, and the coal black steeds attached to the men's coach. One notes the uniforms and white ribbons. But why the separation of men and women? What a race these four-in-hands could perform down Main street, with the bugles blowing and dogs barking!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

April 1929 By Truman T. Metzel, "Charlie Chadbourne" -

Article

ArticleThe Vicissitudes of South Hall

April 1929 By Edwin J. Bartlett -

Article

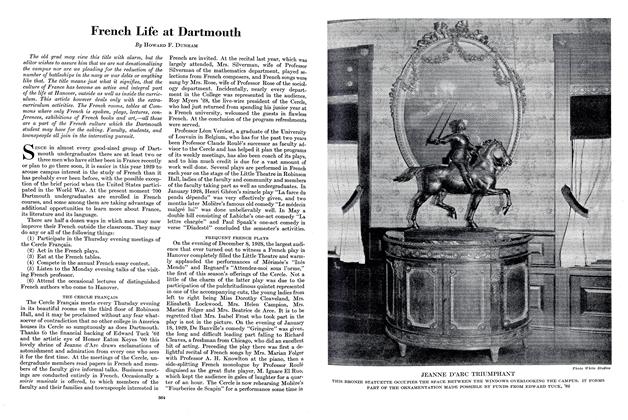

ArticleFrench Life at Dartmouth

April 1929 By Howard F. Dunham -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

April 1929 By Louis P. Benezet -

Article

Article"The Dartmouth," An Explanation

April 1929 By W. L. Scott, Editor -

Article

ArticleMaking Athletes Out of Freshmen

April 1929 By Coach Sidney C. Hazelton

Lettter from the Editor

-

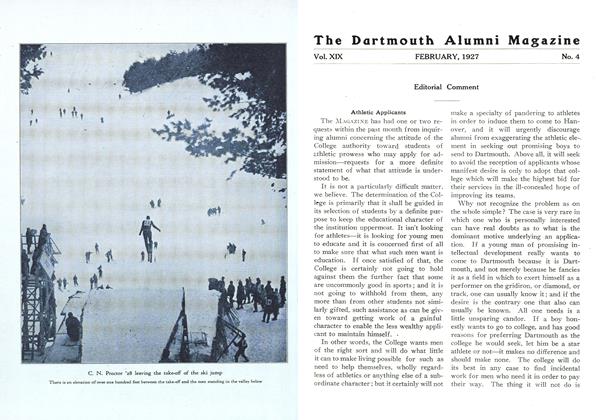

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

FEBRUARY, 1927 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWith Other Editors

APRIL 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

November 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorIn Keeping With This Month's Cover Story, The Review Barks Up Dartmouth's Tree.

MAY 1992 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPostscript

JUNE • 1986 By Douglas Greenwood