This may be said to constitute the back-bone of a course in philosophy in Dartmouth College. At the same time, the ideal of philosophy in a liberal collegeas already described—demands a fuller and richer philosophical curriculum. Courses too numerous to mention here make direct contacts between philosophy and the other departments of the curriculum. Specific courses, such as The Philosophy of Economics and the State; Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art; Philosophical Ideas in Contemporary Literature; and Hindu Philosophy, enable students in these various fields to become familiar with the philosophical aspects of their subjects. More and more courses of this nature are being used as complementary courses in other majors. On the other hand, more advanced courses and seminars in special fields of technical philosophy afford the oppor tunity for more intensive work for those majoring in philosophy.

This idea of philosophy in a liberal college determines not only the form of the curriculum but also the spirit in which it is administered. It affects the policy of the department with respect to the new system of major studies and the general spirit of its philosophical teaching.

We recognize that the numbers of those who major in philosophy for practical ends must in the nature of the case be very few. Again, interest in philosophy normally arises very late in the intellectual life of American students. The early choice of majors requires the student to make his decision before he knows what philosophy is or has an opportunity to become acquainted with the field. We believe that the philosophical training is of advantage as a preparation for many professions and activities, but owing to the conditions described, we expect and encourage only those to major in philosophy who have the love of wisdom in the ancient sense and are willing to lay their foundations broad and deep. The primary function of philosophy in a system of majors such as ours—organized as it is around single subjects—should, we believe, consist in offsetting the tendency to specialization by offering suitable compli mentary courses.

The spirit of philosophical teaching in Dartmouth is also affected by the ideal described. It is frankly constructive and not destructive. The assumption on which much of our higher education is now conducted is that the student needs to be constantly stimulated to destructive criticism and scepticism, and that for constructive thought he may be left to himself. The precise opposite is really the case, as we are gradually coming to realize. The human mind works most easily in the direction of analysis and criticism, whereas it constructs and integrates with the greatest difficulty. Great numbers of our students are left with chaos in their minds, out of which most of them will have neither the time nor the energy to emerge. The older ideals of instruction were frankly constructive, and it was sought to lead the student through processes of thought by which he should at least come to understand and appreciate what was best and most permanent in the thought of the race. We venture to think that in the present state of education one of the most important tasks of philosophy is to subserve this almost completely neglected function.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1879

August 1929 By Henry Melville -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meetings

August 1929 -

Article

ArticleThe One Hundred Fifty-Eighth Commencement

August 1929 By Eugene F. Clark -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

August 1929 By Warren C. Kendall -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

August 1929 By John Crowell -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1918

August 1929 By Frederick W. Cassebeer

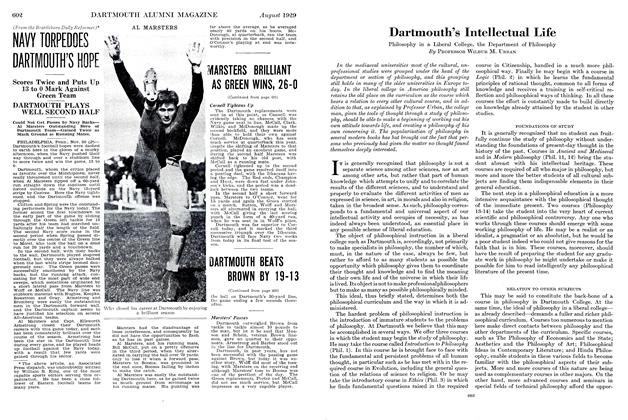

Professor Wilbur M. Urban

Article

-

Article

ArticleMANY COLLEGE GRADUATES IN ELECTRICAL INDUSTRY

June, 1922 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Publications

February 1952 -

Article

ArticleTruman Metzel '23 Given Bequest Chairman Honors

JUNE 1968 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1932 By J. S. M. '33 -

Article

ArticleMid-Hudson

OCTOBER 1970 By JOHN M. COULTER JR. ’58 -

Article

ArticleQualified

October 1940 By The Editor