Philosophy in a Liberal College, the Department of Philosophy

In the mediaeval universities most of the cultural, unprofessional studies were grouped under the head of thedepartment or section of philosophy, and this groupingstill holds in many of the older universities in Europe today. In the liberal college in America philosophy stillretains the old place on the curriculum as the course whichbears a relation to every other cultural course, and in addition to that, as explained by Professor Urban, the collegeman, given the tools of thought through a study of philosophy, should be able to make a beginning of working out hisown attitude towards life, and creating a philosophy of hisown concerning it. The popularization of philosophy inseveral modern books has but brought out the fact that persons who previously had given the matter no thought foundthemselves deeply interested.

IT is generally recognized that philosophy is not a separate science among other sciences, nor an art among other arts, but rather that part of human knowledge which attempts to unify and to correlate the results of the different sciences, and to understand and properly to evaluate the different activities of men as expressed in science, in art, in morals and also in religion, taken in the broadest sense. As such, philosophy corresponds to a fundamental and universal aspect of our intellectual activity and occupies of necessity, as has indeed always been understood, an essential place in any possible scheme of liberal education.

The object of philosophical instruction in a liberal college such as Dartmouth is, accordingly, not primarily to make specialists in philosophy, the number of which, must, in the nature of the case, always be few, but rather to afford to as many students as possible the opportunity which philosophy gives them to coordinate their thought and knowledge and to find the meaning of their own life and of the universe in which their life is lived. Its object is not to make professional philosophers but to make as many as possible philosophically minded.

This ideal, thus briefly stated, determines both the philosophical curriculum and the way in which it is administered.

The hardest problem of philosophical instruction is the introduction of immature students to the problems of philosophy. At Dartmouth we believe that this may be accomplished in several ways. We offer three courses in which the student may begin the study of philosophy. He may take the course called Introduction to Philosophy (Phil. 1). In this course he is brought face to face with the fundamental and persistent problems of all human thought, in particular such as he has met with in the required course in Evolution, including the general question of the relations of science to religion. Or he may take the introductory course in Ethics (Phil. 3) in which he finds fundamental questions raised in the required course in Citizenship, handled in a much more philosophical way. Finally he may begin with a course in Logic (Phil. 2) in which he learns the fundamental principles of rational thought, common to all forms of knowledge and receives a training in self-critical reflection and philosophical ways of thinking. In all these courses the effort is constantly made to build directly on knowledge already attained by the student iii other studies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1879

August 1929 By Henry Melville -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meetings

August 1929 -

Article

ArticleThe One Hundred Fifty-Eighth Commencement

August 1929 By Eugene F. Clark -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

August 1929 By Warren C. Kendall -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

August 1929 By John Crowell -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1918

August 1929 By Frederick W. Cassebeer

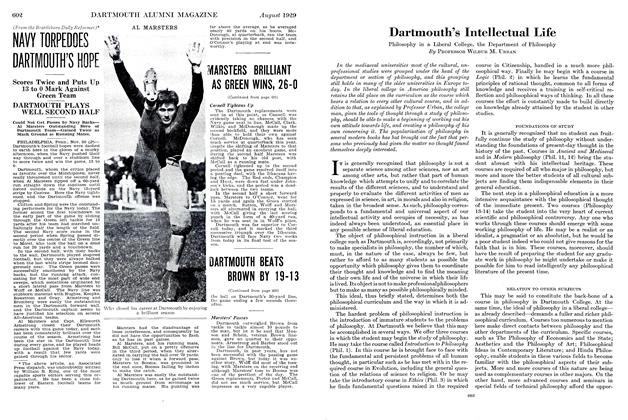

Professor Wilbur M. Urban

Article

-

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF PHI BETA KAPPA

March 1916 -

Article

ArticleMeteorite Collection

December 1940 -

Article

ArticleGifts and Bequests Set Record

October 1956 -

Article

ArticleEugene M. Kinney '44 Heads Alumni Association

JULY 1968 -

Article

ArticleBragging Rites

MARCH 1999 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Carnival

MARCH 1929 By Rolf C. Syvertsen