THE REUNION OFTHE FIFTY YEAR CLASS

"Strange to me are the forms I meet, When I visit the dear old town; But the native air is pure and sweet And the trees that o'ershadow each well known street, As they balance up and down, Are singing and whispering still: 'A boy's will is the wind's will And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts.'

With joy that is almost pain My heart goes back to wander there, And in the dreams of the days that were I find my lost youth again."

Longfellow

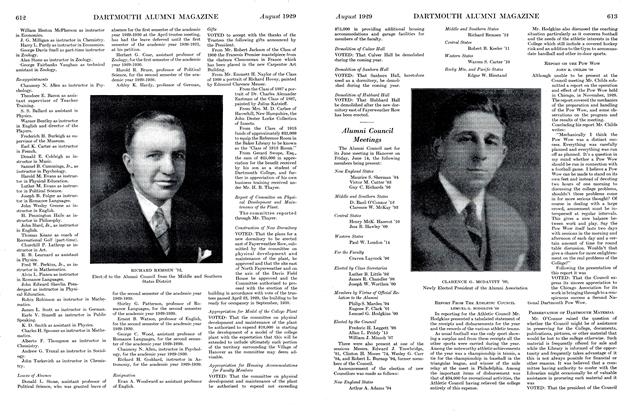

The all star cast, in the order of their appearance, were Thayer, Tebbetts, Melville, Proctor, Nesmith, Wentworth, Closson, Cohen, Rockwood, Gage, Page, Chapman, Bailey, Derby, Graves, Edgerton, Smith, Newell, and Darling. Total nineteen.

Letters and telegrams, usually both letters and telegrams, came from Blair, Clement, Eaton, Garrettson, Norton, and Stanley, who earnestly wished and had hoped to be there, but were kept away by circumstances beyond their control. Blair, Clement, and Norton had reserved rooms at the Inn several months before.

Then there were others, whom we may call the chorus. Mrs. Tebbetts, Mrs. Rockwood, Mrs. Bailey, Mrs. Chapman, Mrs. Smith, Mrs. Hough with Nancy and John, Seth Gage's daughter, Edgerton's son Halsey, Smith's son Howard, Proctor's son Bobwho wasn't of much use to us as he had a ten year reunion of his own to look after—and several family parties; Thayer contributed two daughters and two grandchildren; Derby a brother, a daughter-in-law, a grandson, and a nephew; while Darling had a car full of young people—though he said he left as many more at home. The golden '79 badge was pinned on to over forty individuals, and, as a whole, we did not look at all badly. Of course, as usual, the general average was greatly raised by the pulchritude of the chorus.

We gathered at the Inn, so it is hardly necessary to say that we were lodged and fed in a manner absolutely beyond adverse criticism.

All we met in Hanover, from the officers of the College down to the youngest bell hop, seemed to vie with each other in showing us courtesy and kindness.

A spacious parlor was reserved for our headquarters, but it was not much in use. The rival attractions of the porch and dining room were too strong.

The first arrival was on Monday, June 10, and the last departure Wednesday p.m., June 19. As soon as two were present the reunion began, and continued, uninterruptedly, as long as two remained.

Friday afternoon, when most were coming in, they were greeted by salvo after salvo of Heaven's artillery, with an accompaniment suited for a class that started the "Wet Down." The restless "Tansy" Wentworth, who refused to delay for a moment an investigation of the old road to the bridge, over which he had passed so many times, and the Tuck Drive, which he had never before seen, was a special recipient of the latter, necessitating temporary retirement from the festivities.

As things developed, the northeast end of the porch became the center of attraction. We could sit there, at our ease, and see the graduating class, looking the size of an army, parading about the campus, the younger returning classes disporting themselves in bizarre costumes, and the flood lights from the Baker tower at night. We could hear the chimes and the trumpeters, from the same tower, the singing of the classes of '14, '19, and '24, gathered at the Senior Fence, and the three open air concerts given by the College band, and last, but by no means least as an attraction, it Was a convenient point for a quick get-away when the dining room was opened.

From here scouting parties would go out in all directions to observe things old and new and return to tell us all about their impressions. Then, every few minutes, a bell boywould page the Secretary to deliver another letter or telegram, which would be passed around and form a text for new reminiscence and discussion. Some of us could not see quite as well as formerly and others were a little hard of hearing, but not the slightest evidence of dumbness was ever apparent. We talked and talked and talked.

Collectively, the party probably saw everything worth seeing, but certainly no one person saw everything. There was too much of interest and too little time. It passed like a dream.

Saturday evening many of us went to the undergraduate performance in Webster Hall. The "play" was just another of those things, but the singing and the dancing were fine. One of our ladies, observing the ravishing beauties of the cast, with their deep contralto voices, and the nymphs of the corps de ballet, remarked that they were "not quite convincing,"whatever that may mean—but they certainly made a deep impression on the susceptible hearts of our bachelor members.

Sunday morning those of us who had foresight enough to go to the chapel long before the appointed time heard the baccalaureate sermon, which was interesting and possibly epochal. It certainly was "modern," and possibly would not have been approved in its entirety by some of the earlier presidents of the College. The place was jammed full and it was hot. Several fainted, but no member of '79. Our early training in chapel attendance rendered us immune to any effect from extreme temperatures.

A general reception by the President, at his residence, was announced for Sunday afternoon at 4:30 o'clock, but Dr. and Mrs. Hopkins, in one of those gracious and graceful letters, which only he knows how to write, invited us to come a half hour earlier, at four o'clock, for a little special and private affair. We arrived at the appointed hour, sharp, and our President, Tom Proctor, presented us. There was not the slightest difficulty about securing the arrival, but when four-thirty came and the frantic Secretary tried to get the party out on the terrace to have a group picture taken, his appeals fell on almost deaf ears. All were having much too good a time just where they were. It looked, for a while, as though it might be desirable to call out the entire police department to clear the room, but probably we could not have secured him. The only time we saw him was at the baseball game. Doubtless he is an ardent fan.

Incidentally, of course, we had the first chance at the refreshments, and drank from the only real genuine original silver punch bowl, which Sir John gave to Eleazar one hundred and sixty years ago. We were too polite to inquire as to the ingredients of the brew, but must assume that the traditional five hundred gallons were exhausted some time ago.

In this connection the Secretary is somewhat worried by a remark in a letter of Dr. Hopkins, written the day after Commencement, in which, to a lot of kindly comments on its events he added: "As I looked over the group of '64 men there yesterday, I hoped that members of the class of '79 would eat sparingly, drink discriminately, and observe all other approved procedures which make for longevity." Now what do you think of that! Whom did he have in mind? We all saw those '64 men, a husky, happy lot, but we believe their explanation of such fact would be that coming to reunions has kept them young. Contact with youth is the best preservative of youth.

But, to return to the reception—finally they did get out, and the picture was taken, President and Mrs. Hopkins and Dean Laycock kindly posing with us. In general, there wasn't much ground for complaint with the way it turned out, though, for reasons that need not be gone into, some of us would have preferred to have kept our hats on. In one case, however, only the top of a head showed, a fine head in every way, as far as it went. Whose was it? Some, who hadn't seen him for fifty years, at first said "Dr. Tebbetts." It would have been a pity if he had been in eclipse, for he had come over three thousand miles in order to be present. But others re- plied: "No, there's Tebbetts right in front of him," etc. One thing is certain, Tebbetts was already destined to be the most conspicuous man in the class twenty-four hours later.

Sunday evening, at eight o'clock, we gathered in "Hough's Room." Proctor presided and spoke of the reason for our being there. Then Cohen told of the ideas that prompted the undertaking of the enterprise, and Thayer explained the methods by which such ideas were carried into effect. Finally Dr. Hopkins spoke of the room, the class, and the College. It was an occasion that never will be forgotten.

Later those present signed a much appreciated "diploma" for the Secretary, finer in sentiment and engrossment than a Doctor's degree from the College.

Before separating, we opened the secret vault, beneath the mantel, and deposited the class memorabilia. Among other things we put in a document produced by Primus Smith, which was dated in the spring of '79 and contained a pledge, by upwards of forty members of the class, to contribute twenty dollars each toward Commencement expenses. After one of the first signatures was the word "conditional." Naturally we were all anxious to know what the condition was, suspecting that it might be like the mental reservation many of us had, that we would pay what seemed then such a vast sum, provided we could borrow it. The signer said "No," it wasn't this, but rather on condition that he was allowed to graduate. He did graduate, which was fortunate for him and the class and also for the College. He has since given many thousands of dollars to be disbursed at the pleasure of the President with no condition whatever attached.

Monday forenoon we went to the baseball game and were nearly roasted on the bleachers. Thanks to our moral support, Dartmouth won over Cornell, one to nothing.

In the afternoon came the most discussed event—the "Reception to the Fifty-Year Class." The General Alumni Association met in Dartmouth Hall and, after dispatching its business, adjourned to the tent on the Campus, a huge affair intended, we presume, primarily as a refuge from the rain. Then a strong-lunged young man stepped out and sounded various calls on a bugle—or maybe it was a trumpet; at any rate, it made a powerful noise—and the crowd gathered; it really was a sizable assembly.

At one end of the tent was a platform on which were seated the exhibits (not to say "freaks." It was suggestive of the side-show of a circus). Judge Brown, president of the Alumni Association, made some eloquent and appropriate remarks. Tom Proctor, president of the class of '79, responded with equal eloquence and appropriateness. So far all was decorous and proper. Then Tom introduced the Secretary, who called the roll and, as each was named, he rose, bobbed his head or responded in words as he felt moved. Quite a number did respond, but, sad to say, with no apparent realization of the solemnity of the occasion—in fact a decided spirit of levity prevailed. The audience patiently endured it all, and seemed loth to leave even after Proctor had made no less than three attempts to dismiss them. And then Carey Thayer pulled a stunt not on the program.

It had been discovered that Tebbetts was our first great-grandfather, the infant being a fine boy, eight months old, due for Dartmouth in the class of 1950. A local dealer had been rather nonplused when a committee waited on him and demanded a "trophy" suited for the occasion. What was finally purchased was a silver porringer with an inscription.

Thayer arose and in a clever speech of some length, which, until the end, gave no sign of what it was leading to, presented this loving cup, thus, as before suggested, making its recipient the most conspicuous and envied man in the class.

That evening there was the concert of the Associated Musical Clubs.

Tuesday occurred the Commencement exercises. Many do not realize what an exclusive affair this has come to be. For years the three lower classes have been sent home the previous week so that their dormitory rooms may be available for visitors, and no undergraduate saw any graduation except his own; and, after his own, he was due to wait fifty years before an opportunity to see another. The fifty year class has heretofore been able to get in. So did we, but, as it were, by the skin of our teeth.

When the procession formed, we were mustered by tall Professor Proctor, honored son of our Professor Proctor, who tried so hard to teach us Greek, and were personally escorted by two members of the Alumni Council. The plan was for us to sit imme- diately behind the graduating class. And this seems a good place to speak of the size of such class. We were told that there were 439 in line; that one more was in the hospital but his diploma would be carried to him; and that No. 441 would get his when and only if he learned how to swim—showing the widening of the curriculum.

When we saw their vast array, we were sorry for them. What can one of them know about most of his classmates, fifty years from now?

Well, the class of '29 divided at the door of Webster Hall, and we marched in between the ranks and were assigned to the next to the last row of seats. Then the young men came in—a train of them that it seemed would never end. Nearer and nearer to us they approached and, finally, were clear back to us and yet more remained. Evidently someone had miscounted or else, swelled up with their gowns and self-esteem, they took up more room than had been expected.

The officials hastily cleaned out the protesting occupants of the rear row and we moved back. Had there been twenty-five more of the caps and gowns we would have moved right out onto the campus. There probably will be twenty-five more next year. So it looks as though we have taken part in an historic event—the last viewing of the bestowal of degrees by any of the alumni of the College—unless they revert to first principles, and, as at the first Commencement, have the exercises out of doors in a pine grove.

Our "Carey" Thayer was made a Doctor of Laws, and, when the President said a few kind words and the hood was placed about his shoulders, we made our presence known; but the general and long continued applause indicated that no special claque was necessary.

So far as we could judge everything was done properly, except that President Hopkins did not wear his customary Henry VIII hat, which might cast doubt on the regularity of all the proceedings. Then followed the lunch in the gymnasium, at which Proctor spoke for the class of '79 and was a worthy representative. One of our number, as he reviewed those teeming days, remarked fervently, "I didn't realize that it was going to be anything like this."

Hanover is a unique place. The business portion is no larger than in our day. In this little village, during term time, are gathered twenty-two hundred young men, with no extra-collegiate "resorts" except one movie theatre and about three drug stores. They make their own social life. Do they enjoy it as much as we did when the numbers were smaller?

On Class Day, fifty years ago, our poet Closson sang:

"The lesson's ended. Sadly I give o'er, Knowing full well it is forevermore. The dying echoes warn me to begone, And yet, reluctant, still I linger on. Ah, urge us not too closely; spare our sorrow Who can look forward to no fair tomorrow. Alas, gone from us are those four years bright, Taking what darling treasures in their flight. Farewell, our youth. Farewell, days free from care. Farewell, these friendships generous and rare.

With heavy hearts, and moisture-laden eyes, We pass out 'tween the gates of Paradise."

In a book on American colleges and universities, entitled "Twenty Years Among the Twenty Year Olds," the author, Mr. Hawes, (Yale) has a long and appreciative account of present day Dartmouth, concluding with these words, "Perhaps these memories of the big outdoor world react on the mind and are the reason, in part, why the average student and indeed some alumni unconsciously eon fuse Heaven with Dartmouth and transform Hopkins, indistinctly, into God. We may smile at the boyish enthusiasm; but, after all, it is perhaps better for youth than a too critical spirit and reliance on actual facts. Dartmouth is certainly one of the best places to send a boy."

"Paradise" thus seems to have become "Heaven." Extravagant expressions, of course, but not so much so as might appear to the uninitiated.

The only sad faces we saw in Hanover were those of the class of '29.

Whatever else has changed, the sentiment of Dartmouth's sons toward their Alma Mater seems to continue much the same.

Secretary,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meetings

August 1929 -

Article

ArticleThe One Hundred Fifty-Eighth Commencement

August 1929 By Eugene F. Clark -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

August 1929 By Warren C. Kendall -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

August 1929 By John Crowell -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1918

August 1929 By Frederick W. Cassebeer -

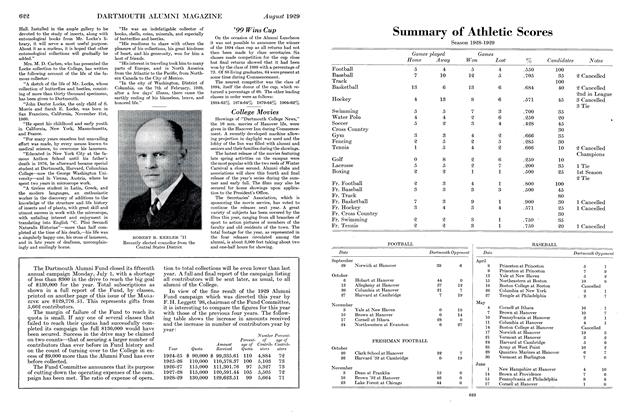

Sports

SportsSummary of Athletic Scores

August 1929

Henry Melville

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1879

January 1921 By Henry Melville -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1879

February 1921 By Henry Melville -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1879

March, 1923 By Henry Melville -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1879

January 1924 By Henry Melville -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1879

DECEMBER 1927 By Henry Melville -

Class Notes

Class NotesSecretary, 165 Broadway, New York

APRIL 1928 By Henry Melville

Class Notes

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1931*

December 1942 By CHARLES S. MCALLISTER, WILLIAM A. GEIGER -

Class Notes

Class Notes13

MAY | JUNE By Emily Fletcher -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

APRIL 1988 By H. Donald Norstrand -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

MARCH • 1986 By Harry R. Zlokower -

Class Notes

Class NotesNew York City

November 1954 By HERBERT M. BALL '29, RALPH SMITH '46 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905*

April 1939 By ROBERT H. HARDING