William J. Rose, Jonathan Cape, London, 1929.

Stanislas Konarski was born in the opening year of the most tragic century of Polish history—the century of the partitions. The significance of his life and work lies in the fact that he was among the first of his countrymen to foresee the disastrous trend of political and social conditions within the state, and to seriously suggest and attempt reform. In no small measure his labors made possible the regeneration of Poland that followed the first partition of the unfortunate state in 1772.

Professor Rose begins his study with a sketch of the political and social life of Poland in the XVIIIth century—an essential background for understanding the dire need of reform within the state, and the particular problems that Konarski faced. And never was state in more unhappy plight than XVIIIth century Poland. Without the state were powerful and unscrupulous neighbors ready, as time proved, to partition the nation at the first convenient opportunity; within, confusion approaching anarchy prevailed. The elective kingship occasioned not only constant quarreling and intrigue among the great families, but led increasingly to outside interference. Even more disturbing to the peace of the state was the wretched liberum veto by means of which the Seym, or Diet, might be "exploded," and the entire public business blocked by any member who believed his personal interests jeopardized. Of effective military strength there was none. Nor were social conditions any better. The magnates owned the land, played politics and looked after their own selfish interests, while the mass of the nation were reduced to a state of serfdom and wretchedness hardly equalled in Europe. The decline of the towns had left the state without the rich and powerful middle class which might have given the proper balance to the whole social order. Morals were decadent, as elsewhere in XVIIIth century Europe, while education, in the hands of the Catholic orders, had become formal and lifeless, impotent to effect reform through the proper training of the nation's youth. Decidedly, if reform was ever needed to preserve the existence of a state, it was needed in XVIIIth century Po'and.

Stanislas Konarski, "the wisest of the Poles," and, until his death, the leading spirit in the struggle to save Poland from itself, came from a family of the middle-class gentry. He was educated in the schools of the Piarists, a teaching order of the Catholic church, and at the age of seventeen entered the Order that he might devote his life to the cause of education. That he proved a student and teacher of unusual promise is indicated by his rapid rise in the Order, and by the opportunity soon offered him for further study abroad. Six years of study in Rome and Paris brought him into contact with the best educational thought of his age, and more particularly with the educational theories of John Locke and of the French thinker, Charles Rollin. With - the work of Comenius, another powerful influence in the shaping of his own thoughts on education, he was probably already familiar.

His studies in the West must have convinced Konarski of the dry rot of verbalism that affected the schools of Poland, but it seems to have remained for several years of disillusioning experience in the vexed political life of his country to awaken him fully to the vital need of educational reform if the nation was to be saved. By 1740, however, he was ready for his life work, and that year saw the establishment of his CollegiumNobilium in Warsaw. It might seem strange that Konarski should have begun his educational reforms with the establishment of a School for Gentlemen's Sons, but these were to be the rulers of Poland, and it was Konarski's belief that upon the soundness of their education depended the future welfare of the state. The course was one of seven years with an additional two for those who wished to enter public life. Among the striking innovations in this model school were the approach to knowledge through the native speech, the emphasis upon subjects having a practical significance for daily living, the elimination of learning by rote and of learning by repetition in groups. Furthermore, believing in the virtues of individual work, Konarski insisted, in spite of parental opposition, that each student have his own books. And to these texts Konarski himself contributed an improved latin grammar and a treatise on The Correction ofOur Speech which struck at the roots of the excessive verbalism of the day. All in all, the Collegium Nobilium proved an experiment in keeping with the best educational practice, clerical and secular, of Konarski's age.

With the Collegium Nobilium successfully launched, Konarski turned his attention to a thorough going reform of the educational methods of the Piarist order from which the teachers of the new college were drawn. In this effort he met with no little opposition, but in the end his program of reform, as embodied in his "Ordinationes," was accepted by the Church and put into operation. The result was a revolution not only in Piarist methods of teacher training, but in the curriculum of the Piarist schools as well. New subjects were added and better methods of handling the old introduced. More attention was given to the national language and literature, and worthwhile essays on the questions of the day suggested. Class room discipline was improved, and to complete the reform two efficient normal schools were established with a new emphasis upon scholarship and specialization. So satisfactory did these reforms prove that eventually even the rival Jesuit order was forced to follow suit. Moreover, they affected a much wider class of Polish society than did the Collegium Nobilium.

In these sweeping educational reforms undoubtedly began the regeneration of Poland, and as they made themselves felt the number of those increased who looked to the Piarist father as the "Preceptor of Poland" in the "fight for responsible citizenship." Nor was Konarski averse to playing such a role, for responsible citizenship had been his goal from the first. For years he had watched with concern the disastrous course of national politics, and his Effective Counsels (1760-1763) was the fruit of an intense study of Polish history and political institutions. The major thesis of this great work was the necessity for eliminating the curse of the liberum veto and establishing majority rule in the Seym. He also proposed measures that would insure the nation a sound and orderly government, involving the reform of the national and local seyms, and the establishment of a permanent Council of State.

Unfortunately Konarski died in 1773, in the year following the first partition, but in the awakening of Poland which followed that tragic event many of the reforms he had suggested were adopted either in whole or in part by the nation. It is significant of the effect of his work that following the publication of his Effective Counsels no more Seyms were "exploded," and that in 1791 the party of reform was able, not only to abolish the liberum veto, but to give to Poland a modern constitution. Unhappily, reform in this instance came too late, and the partitions of 1793 and 1795 put an end to the Polish state for a century and a quarter. Yet there can be little doubt that the great movement initiated by Konarski did much to bring about a spirit of Polish nationality that made the Polish question a constant factor in European politics through the nineteenth century, and eventually made possible the astonishing resurrection of Poland at the close of the World War.

Professor Rose has treated his subject in an interesting and scholarly manner. He has based it soundly upon the contemporary Polish sources, and in so doing has added much to our knowledge of a neglected phase of European history—the social and intel- lectual history of the last century of the old Polish kingdom. Incidentally, the study is unique in being the first thesis presented for the doctorate at the ancient Polish univer- sity of Cracow for upwards of four hundred years by a representative of the English speaking peoples, and the very first by a scholar from the new world.

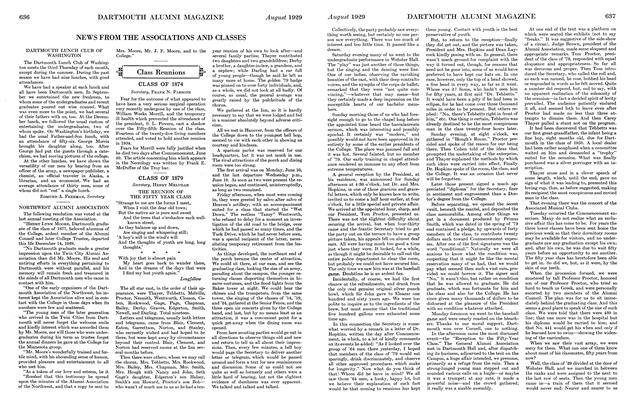

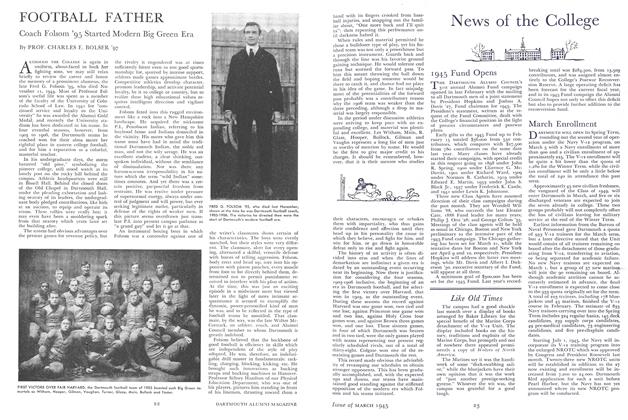

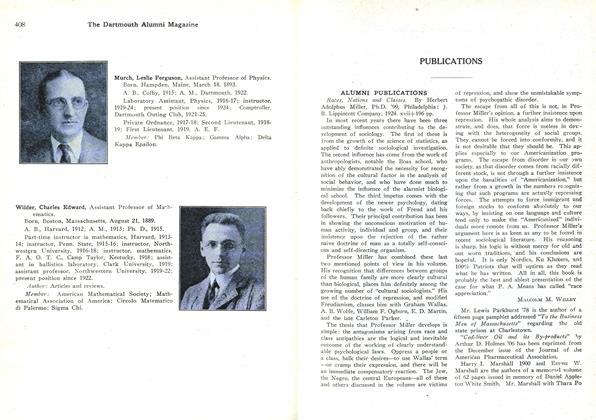

CLASS OF 1880 BASEBALL NINE Back row: Morton, c. f., Hallman, p., A. L Spring, r.f.; middle row: Sutcliffe, captain, catcher, Ripley, s. s., C. W. Spring, 9h, front row. Webster Thayer, lb, Field, 1.f., Warner, 3b

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1879

August 1929 By Henry Melville -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meetings

August 1929 -

Article

ArticleThe One Hundred Fifty-Eighth Commencement

August 1929 By Eugene F. Clark -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

August 1929 By Warren C. Kendall -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

August 1929 By John Crowell -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1918

August 1929 By Frederick W. Cassebeer

W. R. W.

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

March 1916 -

Books

BooksBravey Heart

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2021 By DAVID ALM -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

MAY 1970 By F.H. -

Books

BooksMY QUEST FOR FREEDOM

June 1945 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksGEORGETOWN HOUSES OF THE FEDERAL PERIOD,

March 1945 By Hugh Morrison '26. -

Books

BooksRaces, Nations and Classes.

March 1925 By MALCOLM M. WILLEY