THE AESTHETICS OF THE RENAISSANCE LOVE SONNET: An Essay on the Art of the Sonnet in the Poetry of Louise Labe

MARCH 1963 FRANK G. RYDERTHE AESTHETICS OF THE RENAISSANCE LOVE SONNET: An Essay on the Art of the Sonnet in the Poetry of Louise Labe FRANK G. RYDER MARCH 1963

By Lawrence E. Harvey Geneva: Librairie E. Droz, 1962. 84 pp. SFr 12. $3.00.

The twenty-four love sonnets of Louise Labe record the struggle of an ardent spirit to establish, in the Renaissance world of here and now, without benefit of medieval transcendentals, an ideal vision of love permanent enough to withstand time and mortality — and frustration. The fact that the struggle as such was doomed to precariousness or failure has no adverse effect on - perhaps it even augments - the stature of the poems. They stand as major works of an important period of French literature, in a poetic form of enduring fascination. They have now received their first critical due, in Professor Harvey's full, responsible, and sensitive examination. Illuminating the specific structure and content of these sonnets, he has also contributed substantially to our understanding of the esthetics of the sonnet in general. Anyone who wishes to see what the revolution in literary criticism of the last few decades is about, in specific application, will profit from the reading of these pages.

A brief review can give no idea of the range of perspectives under which Mr. Harvey has studied the sonnets or of the pains with which they are analyzed and interpreted, singly or in groups, until they yield their meaning as fully as poetry can be persuaded to. Let me indicate only one of the insights which I found absorbing. The basic struggle of the poetess is manifest not only in varying degrees of joy and despair, of lyricism and tragedy, but in a wide and eloquent roster (in terms of content) of the tensions of love: between lover and beloved, lover and world, lover and non-lover; between union and separation, happiness and suffering, permanence and time - dualities presided over by a sense of the omnipotence of Amour. In harmony or counterpoint with these, and within the supposed rigors of the sonnet form, Professor Harvey discovers manifold tensions of structure: between form and content, expected form and actual form, form as victory and content as defeat; as well as coexistent or rival patterns within the same sonnet. He exhibits Louise Labe's fascinating variety of counterbalances to the "normal" 8-6 division of the sonnet lines: 10-4, 8-1-5, seven distichs, and a multitude of others, each determined by a facet of meaning or syntax - as well as refinements of the traditional division involving specific present in the octet, hypothetical future in the sestet, and so on.

Any reader interested in the range of formal features that can be adduced in establishing the meaning of a poem will admire Professor Harvey's handling of such diverse phenomena as configurational patterns, images (in which the poems seem richer than is conceded), morphological matters such as tense change, and prosodic elements like enjambement.

This is a wealth of material, exhaustively treated. The present book is probably not the place for it, but the general reader might welcome a listing of similar approaches to other bodies of poetry, the modern approach to "close reading" from which the author draws inspiration — and to which in turn he contributes in exemplary fashion.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePOETRY AT DARTMOUTH

March 1963 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Feature

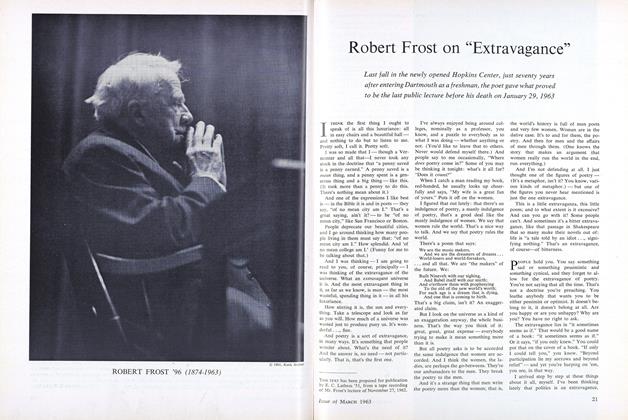

FeatureRobert Frost on "Extravagance"

March 1963 -

Feature

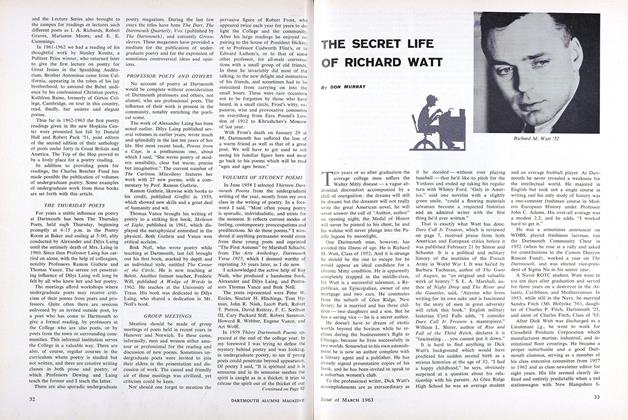

FeatureTHE SECRET LIFE OF RICHARD WATT

March 1963 By DON MURRAY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

March 1963 By JOHN HURD, HUGH M. MCKAY -

Article

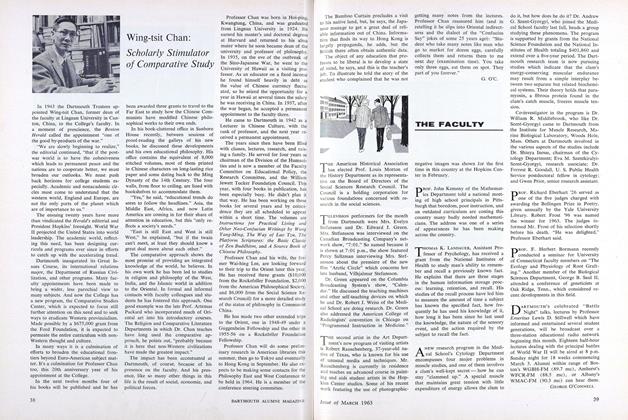

ArticleScholarly Stimulator of Comparative Study

March 1963 By G.O'C. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1963 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, ALBERT W. FREY

FRANK G. RYDER

Books

-

Books

BooksSINCE 1900

May 1948 By Allen R. Foley '20. -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN ITALY.

May 1953 By George C. Wood -

Books

BooksThe Start of It All

September 1975 By J.H. -

Books

BooksBEGINNING SPANISH.

November 1955 By JOSEPH B. FOLGER '21 -

Books

BooksTHE NATURE WRITERS, A GUIDE TO RICHER READING

February 1939 By Robert McKennan '25 -

Books

BooksA MASQUE OF MERCY,

December 1947 By STEARNS MORSE.