The critical estimate of one poet by another is usually avery interesting piece of work, and in the case of RichardHovey extremely desirable. Hovey's most meritorious workis but little known to most Dartmouth men, and for thatreason the editors consider themselves fortunate in havingthis article by Mr. Laing whose poems in this generationare drawing the attention of contemporaries just as Hovey'sdid in his.

WHEN Richard Hovey died of apoplexy on February twenty-fourth, 1900, he was widely regarded, both at home and in England, as one of the very few fine poets whom America had produced. A chronological inspection of his eleven volumes containing original verse reveals a steady growth in technique and in restraint; he had never lacked power. Another decade might have carried him to unique eminence; but this speculation is futile. He died at thirty-five; and what he might have done cannot concern us.

Rather it is a matter for concern that he left uncompleted a major work temporarily and unaccountably forgotten, his Arthurian cycle entitled Launcelot andGuenevere: A Poem in Dramas. Reviewers of Robinson's "Tristram" were careful to compare it with poems by Swinburne, Arnold, Tennyson, and Morris, as well as with early sources. It is proof of the limbo into which Hovey's work has fallen that no-one compared Robinson's with his, which for this purpose is one of the most significant; no-one, to be strictly accurate, excepting the present writer.

Although Robinson mirrored the society of his own day in an antique setting no more frankly than Tennyson did, his has been called a truer work because we are nearer than the Victorians were to the ethics of early Britain. Hovey did a larger thing; he looked ahead of his time; and while most American poets were following a foreign decadence, he used an old garment to clothe the prophecy of a new day. In his treatment of society he anticipated Robinson by twenty or thirty years.

It may be argued that Robinson's critics ignored Hovey because he did not devote a whole poem to Tristram. Yet his treatment of the Arthurian scene is so similar to Robinson's that this is small excuse. His status as the only other American to make creditable use of the legends is enough excuse to require comparison. Frankly, few critics know that Hovey wrote anything except his vagabond songs. His more important work has been forgotton, a fact excusable neither because of its incomplete form nor upon lack of original notice. Four of the nine projected books were published during the lifetime of the poet; and a fifth containing fragments of the others was issued posthumously. Many press notices attest the international acclaim accorded them. A critic of The New York Times wrote: "Nothing modern since . . . (Atlanta in Calydon) surpasses them in virility and classical clearness and perfection of thought." Another in The NineteenthCentury said, "It requires the possession of some remarkable qualities in Mr. Richard Hovey to impel me to draw attention to this 'poem in dramas' which comes to us from America . . . Shows powers of a very unusual quality,—clearness and vividness of characterization . . . ease and inevitableness of blank verse, free alike from convolution and monotony." And of "Taliesin," the last complete book, Curtis Hidden Page wrote in The Bookman, "It is the greatest study of rhythm we have in English. It is the greatest poetic study that we have of the artist's relation to life, and of his development." When a careful scholar names any work greatest in his own field of study, it merits the inspection, at least, of the next generation.

HIS SERIOUS WORK NEGLECTED

Hovey, like many another, has been the victim of anthologists, who have seized upon a few riotous vagabond songs, neglecting his more important and restrained work. Even the once übiquitous "Stein Song," sung by thousands who did not know the name of its author, died away when saloons had to be quiet if they were to survive.

Anthological misrepresentation has given so false a perspective of the poet's whole work that in simple justice to the dead it should be corrected. Few think of Hovey as other than an unbridled singer who subordinated thought to spontaneity. This was an important part of his genius; but it was not a period. It was a cathartic strain, a parallel outrider of his more serious work. Hovey considered his Arthurian poems his opera. Proof that a well-ordered plan for them was in mind before the composition of the vagabond songs exists in a page of manuscript, dated January, 1889, which contains what was to be the last speech in the last drama. It was the first to be written.

In a preface to "The Holy Graal," the posthumous volume of fragments, Bliss Carman says this of the poet's purpose in writing "Launeelot and Guenevere:"

"He had at heart and in mind some frank solution of perplexing human relationships, and needed an adequate plot to make his solution clear and telling.

"The problem he felt called upon to deal with is a perennial one, as old as the world, yet intensely modern, and it appealed to him as a modern man keenly alive to all the social complexities of our civilization. But, for all that, he wished to get away from the modern setting for his drama, so that the exposition of his ideas might not be confused by the baffling counter interest of contemporary realism.

"Two courses were open to him, therefore. He could either find some ample, plastic, and familiar plot ready to hand,—ample enough to lend dignity to his characters, old and vague enough to be treated freely, and familiar enough to easily command attention; or he could create a plot of his own and people it with strange and unaccustomed names, after the manner of Maeterlinck. He chose the former alternative."

From Hovey's own pen, however, we have complete proof of a social intelligence such as, although it sometimes appears inspirationally, seldom is articulate in any poet: a few pages of manuscript which he labeled "Schema," the complete and careful plan of the unfinished cycle. Although rather long, it merits reproduction in full, in order that we may understand how different a man Hovey was from what he has been imagined, and may understand the poet's purpose, which is revealed only in part in his arrested work.

SCHEMA

LAUNCELOT AND GUENEVERE

Part I.— The Quest of Merlin: A Masque. The Marriage of Guenevere: a Tragedy. The Birth of Galahad: a Romantic Drama. Part II.— Taliesin: a Masque. The Graal: a Tragedy. Astolat: an Idyllic Drama. Part 111.—Fata Morgana: a Masque. Morte d'Arthur: a Tragedy. Avalon: a Harmonody.

COMMENTARY

Note that each of the three parts is composed of (1) a Masque, i.e., a musical (operatic) interlude or prelude, foreshadowing the events to follow, dealing with the supernatural elements of the myth and symbolizing the philosophic, aesthetic, and ethical elements of the series; (2) a Tragedy; and (3) a play ending with a partial (Parts I and II) or complete (Part III) reconciliation and solution.

Launcelot and Guenevere are placed in a position where they must either sacrifice the existing order of things to themselves or themselves to the existing order of things.

Part I.—They attempt to set their relation to each other above their relation to the world. Tragic issue. (Thesis.) Part II.—They attempt to set their relation to the world above their relation to each other. Equally tragic issue. (Antithesis). Part III.—The reconciliation. (Synthesis). Subordinate to this, as a background: Part I deals with the growing power of the Round Table, the rise of Arthur, and culminates with Arthur's highest reach of empire. (Great event in the legends The Roman War.) Part II with the height (stationary) of the power of Arthur and the Round Table and the first mutterings of their impending fall. (Great event in the legends The Quest of the Graal.) Part III with the fall of Arthur and the Round Table. (Great event in the legends The Last War.)

There is an interval of nearly twenty years between Parts I and II, and of five or six years between Parts II and III. But the dramas in each part are immediately successive.

THE MASQUES:The Quest of Merlin foreshadows the events of the whole poem, but particularly of Part I, i.e., the marriage of Arthur to Guenevere. Symbolically, it suggests the philosophical drift of the poem. Taliesin foreshadows the events of Part II (the Graal search, etc.). Symbolically, it suggests the aesthetic drift of the poem. Fata Morgana foreshadows the events of Part III (the treachery of Mordred, the death of Arthur, etc.). Symbolically, it suggests the ethical drift of the poem. They might be called "the Masque of Fate and Evolution," "the Masque of Art" and "the Masque of Evil" respectively.

THE PLAYS: Part I—lndividual and sex relation (true family) set above Society or the State: (a) Marriage of Guenevere—(Love overthrowing friendship as well as more general social obligations); (b) Birth of Galahad—(Love still supreme, but seeking and partly finding a way to be loyal to friendship and the State, too.) Part I, Tragic; (a) all tragic; (b) partly reconciliated. Part II— Society and the State set above individual and sex relation or true family: (a) The Graal—(Love renounced; religion sought as means of renunciation. Failure of attempt.); (b) Astolat—(Gradual reconquest of love over religion, etc., etc.). Part 11, Tragic; (a) all tragic; (b) partly reconciled. Part lll—Reconciliation of Religion, State, Society, Family, and Individual: (a) Morte d'Arthur—(Essential conflict made objective and settled with the sword. Tragic solution of Death.); (b) Avalon-—(True harmonic solution). Part 111, Harmonic; (a) tragic; (b) completely harmonic or reconciled.

In our era of outlines this one deserves careful study, for study proves it to be a summation of most of the essentials of human thought and relationships. When one reaches the words, "true harmonic solution," the tragedy of Hovey's early death becomes poignant; for it seems obvious that he had in mind a system for the betterment of social contacts and took the secret with him when he went. This is the vaguest passage in the outline; and there is nothing in the fragments to tell what the solution might have been. It, perhaps, was impractical; but Hovey himself lived so large and full a life while life was his that the incompleteness of his best work is a matter for more than artistic regret.

HOVEY'S ART

Turning from ethics to art, we find a complexity of interest in the poems. Among other things, they form a step by step record not only of the growth of a poet, but of the growth of a poetry as well. The four complete dramas and the fragments show a dual evolution. It is foolish to deny that the first is rather bad as a whole work. It is amorphous, melodramatic in the unfor- tunate sense, and written in an idiom largely derived from other poets, especially from Swinburne. Verses such as these are evidence: "Speed, black Night, from the hooded east! Bring to our nostrils the smell of the feast! Bring the locks unbound and the limbs released And the tigerish lover that bites the breast!"

But on the second page following, Hovey's own joyous note appears: "Come, old wherefore-seeker, Let the fates go flying! See within the beaker Joy imprisoned lying," etc.

The masque is a strange mixture of Norse, Greek, and Christian mythology, written in continually shifting rhythms. In it Merlin seeks among the gods and halfgods for a solution of the problem which he has forseen in Camelot. He receives ambiguous replies, and learns his own tragedy: that he can predict, but cannot alter, the course of fate. This affirms a suspicion which is voiced earlier in the play: "... Alas! The wisdom of the old Is like a miser's hoard—laid up in toil To lavish on a mistress—she being dead, The old man counts his useless treasure over, More joyless that it once had brought such joy."

Early reviewers objected to the Norse and Greek themes in an Arthurian poem; but Hovey's purpose in using them is obvious to one who has read the Schema. He was not dealing with the legends for their own sake. He made them a localization of the universal both in time and in space. Therefore his heterodox use of mythologies is justifiable, necessary. In his conversations with the immortals, Merlin reveals much of the problem which is to be unrolled in England; and if much of the poetry is uninspired, Hovey accomplished his aim: to outline the philosophical basis of the cycle. Here too we find the germs of the new poetry which was to supplant the Victorian tradition. Stephen Crane's "The Black Riders" has been called the first book of a terser, non-Whitmanesque free verse which flowered widely about 1910. Yet much of "The Quest of Merlin" was written in this style, anticipating Crane by nearly a decade. Prosodically, however, the book is little more than a record of conflict with old influences.

The transition from it to the next drama is startling. "The Marriage of Guenevere" gives no hint of the seething, derivative metres of "Merlin." It is written almost entirely in restrained, sure blank verse; although it is not free from poetic diction, it is Hovey's own, and somehow timelessly colloquial. Witness this early speech by Launcelot, in which he tells of his rescue, when fainting from hunger in the wilderness, by an unknown who later proves to have been Guenevere: "There on the peak beyond the gulf I saw her, Standing against the sky, with garments blown, The mistress of the winds! An angel, said I? God was more kind, he sent a woman to me." Here too we begin to find the strong lines which later become more frequent. "Why talk ye all of Lancelot? His fame spreads westward over Wales like dawn."

In this play the result of Hovey's training as an actor also is revealed. Plot and thesis are perfectly reconciled so that each adds strength to the other, instead of conflicting, as they might easily have done. The conquest of love over friendship is skilfully handled, founded upon the above-mentioned device of a meeting between Launcelot and Guenevere before either knew the other's identity. Their adultery is discovered and exposed by Ladinas, Morgause, and the Roman emissary. But Arthur refuses to believe the charge when the death of Ladinas removes actual evidence. The play closes with these lines: AHTHTJB Good my lords Erase this most unnecessary scene From your remembrance.

Lattncelot. (Half aside, partly to Guenevere and partly to himself) Be less kingly, Arthur. Or you will split my heart!—not with remorse No, not remorse, only eternal pain!Why, so the damned are!

Guenevere (half a-part). To the souls in hell. It is at least permitted to cry out.

THE BREAK WITH TRADITION

Occasional anachronisms mar this play and, to a lesser extent, the others of the cycle. In general, the technical comment upon it applies as well to "The Birth of Galahad," which differs only in a more obvious mastery of technique. It has fewer high passages, and also fewer faults. In it the last remnants of the influence of other poets disappear. It contains Hovey's most marked break with the legends: the birth of Galahad to Guenevere, in secrecy, while Arthur is besieging Rome. Launcelot, in lines spoken to Galahault in camp on a bank of the Rhone, sums up the conflict of loyalties much as it is expressed in the Schema, but more passionately and personally: "I cannot yield her; she's not mine to yield. Love is not goods or gold to be passed on From hand to hand; it is like life itself, One with its owner,—pluck it out to give Another and by that act it is destroyed And no one richer for your bankruptcy. When Arthur puts his arm about my neck And tells me his imperial dreams, how he Will shape the world when he has mastered it, To something worthier man's immortal soul, Keeping back nothing of his heart from me Oh, Galahault, think how I love the man And how my heart must choke with its deceit! It were less miserable to confess to him— But that were tenfold more disloyalty To Guenevere than loyalty to him. Whichever way I turn disloyalty Yawns like a chasm before me. True is false, And false is true; and everything that is, A mocking contradiction of itself. There is no peace for me But to achieve impossibilities."

At another point Hovey half-anticipates Robinson's elimination of the love potion in "Tristram,"which caused much comment. Dinadan has brought news from Cornwall of Mark's treachery to Tristram, and tells the story of the potion, concluding: .... And they two drank thereof And straightway loved each other. AKTHUB. Think you this true? DINADAN. Why, for the potion, be that as it may. I hold it likely Tristram drank some wine, And not unlikely that he kissed the lady; And all, perhaps, without the devil's help.

In Hovey's poem the magic has almost withered away; and in Robinson's it disappears.

"Taliesin" is a return to symbolism, and to varied metrics. Professor Page's comment doubtless is true enough, for the rhythm varies from iambic to Sapphic, in a multitude of stanza forms. Many passages form quotable unit songs. This, sung by a youth born symbolically, and about to descend to the world of evil, is as little damaged by removal from its causation passages as any: "O World! O Life! O City by the Sea! Hushed is the hum Of streets; a pause is on the minstrelsy. I come, I come! The sunlight of thy gardens from afar Is in my heart. A girl's laugh dropped from heaven like a star Leads where thou art. The old men in the market-place confer, The streets are dumb; The sentinels await a harbinger I come, I come!"

This, I believe, is pure lyricism, as slight and as memorable as a song from an Elizabethan play. The following stanza is taken from a longer song. They prove that Hovey could be lyrical without boisterousness: "As the heather glows over the hills Like a shadow ablaze, And the moss of the forest floor thrills Into bloom at thy gaze; The grasses begin to confer And the crickets to fife; The borders of Death are astir With the armies of Life."

"Taliesin" sets the aesthetic mood of the poem as successfully as "Merlin" sets the philosophic, and in better poetry. It, too, suffers from amorphousness and irrelevant lines; but it is a masterwork of technique, and more.

The fragments collected in "The Holy Graal" being discontinuous to prove little, except that they were written by a man reaching the ultimate surety of expression. We must look instead to the Schema for ideas which the five unfinished books were to contain; and there we find the tragedy of a solution hinted but not expressed.

A quarter-century has passed since the death of Richard Hovey. He is not the first poet to suffer a posthumous period of obscurity, or the first to be misunderstood. Although we lack perspective on living poets, we do not lack it to compare him with others dead.

I know of no American of the nineteenth century, excepting only Poe, and Emily Dickinson, who has written better poetry than Hovey's best. Without exceptions I know of none who has left as large a body of superior poetry. His faults were strong faults, those of a period of transition when he, in America, was carving the caryatids for a new house of poetry both in England and at home. English poetry was sinking to its most futile level while he was reaching his highest. That he is not ranked with the few first men of letters whom this country has produced I hold to be, not an indictment of Hovey, but an indictment of criticism.

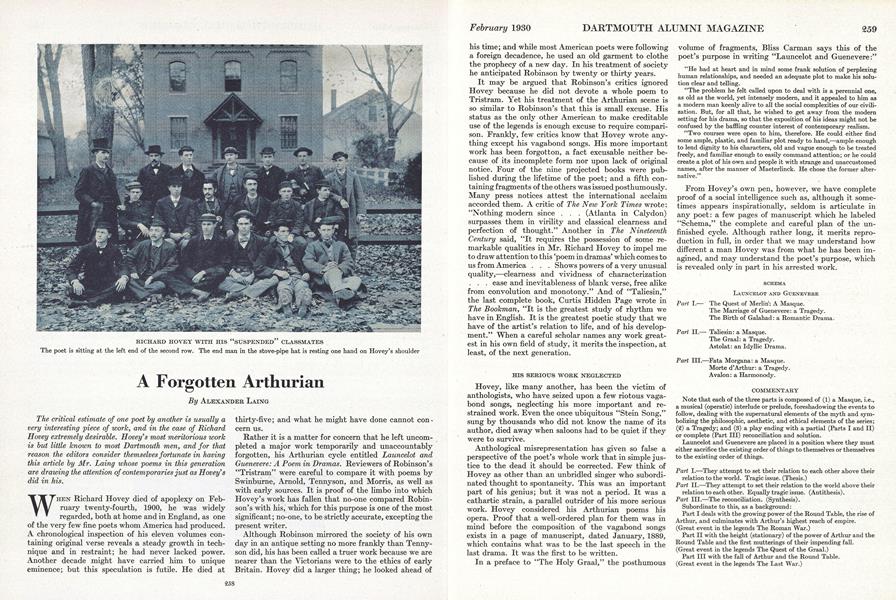

RICHARD HOVEY WITH HIS "SUSPENDED" CLASSMATES The poet is sitting at the left end of the second row. The end man in the stove-pipe hat is resting one hand on Hovey's shoulder

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

February 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1930 -

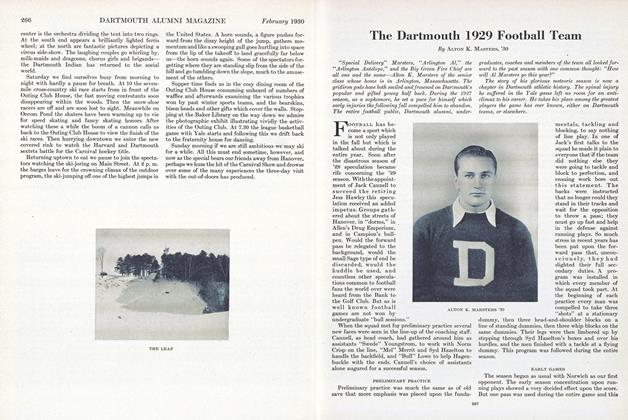

Sports

SportsThe Dartmouth 1929 Football Team

February 1930 By Alton K. Masters, '30 -

Article

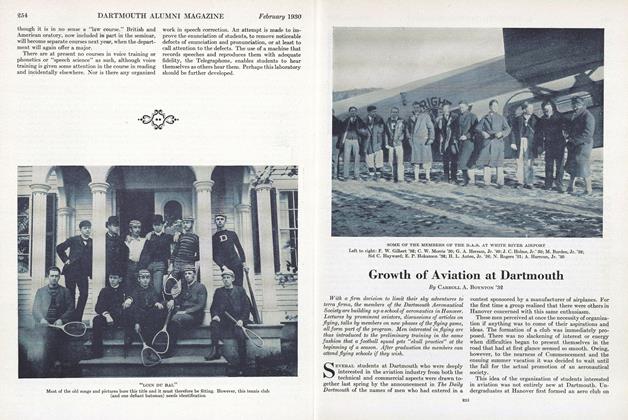

ArticleGrowth of Aviation at Dartmouth

February 1930 By Carroll A. Boynton '32 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

February 1930 By Frederick W. Andres -

Article

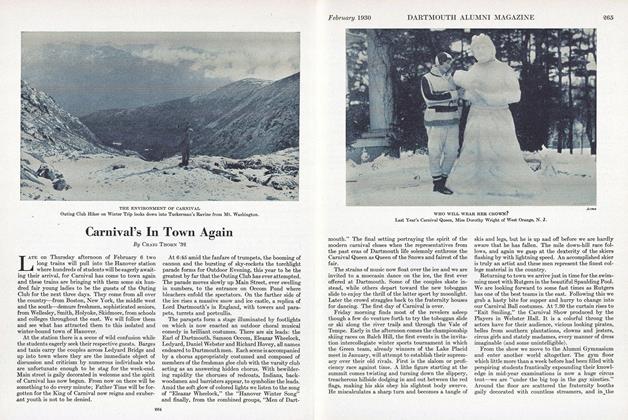

ArticleCarnival's In Town Again

February 1930 By Craig Thorn '32

Alexander Laing

Article

-

Article

Article600 Attend Intersession

May 1943 -

Article

ArticleReynolds Foreign Grants Open to Recent Graduates

February 1956 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Election Results

April 1960 -

Article

ArticleN.Y. Barry Grove

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

Article

ArticleTHE TODD DOSSIER: A DISQUIETING NOVEL ABOUT A CHANGE OF HEART.

DECEMBER 1969 By CARLETON B. CHAPMAN, M.D. -

Article

ArticleClass of 1991

May/June 2004 By John Aguilar '90