DURING the five or six years following my own undergraduate days, I have tried to maintain an informal personal interest in Dartmouth's student poets. The attempt arose logically from the fact that in them two of my keenest concerns, the status of strictly contemporary poetry and that of Dartmouth's intellectual life, are provocatively intermingled. In honesty I must preface more pleasant news with the lugubrious admission that for two or three of those years the poets of Hanover were a most unpromising lot. They were so dreary a group, in fact, that I was beginning to slump into the poisonous, state of mind that makes one's own college years seem akin to the high renaissance in Italy: a golden time that happened never before and never will come again.

This smugness was severely and healthily jolted, last winter, by the discovery of a freshman who was writing verse that seemed quite as good as the average output of the three or four leading seniors of the days that produced The Arts Anthology: Dartmouth Verse 1925. He was not a superannuated freshman, either. I believe that his age is below average for his class.

From here and there came more evidences of a reawakened interest in poetry. Finally, a poetry contest sponsored by The Arts brought out three or four other poets of highly individual merit, and at least ten more who had something to say and a creditable aptitude for saying it. The result is Dartmouth Verse 1930, a new anthology published by the Arts, and thoroughly worthy, in my opinion, to stand beside its predecessor. {By the way, if you have a copy of the first anthology, eitherhold on to it or sell it intelligently, because its price in therare booh market has been steadily advancing. Booksellerslast spring were offering five dollars for it, and selling it forten.) You will find a critical estimate of DartmouthVerse 1930 elsewhere in this issue. I want to tell you here more about the poets than about their poetry.

As I look back upon it now, the fact that there was a heyday for poetry in 1925, followed by a senescence and a vigorous reawakening five years later, does not seem so odd or so unhappy after all. We have been platitudinously assured that poets are born, not made; and there is probably more evidence pointing to the truth of that platitude than of any other. A strongly sympathetic or a strongly antagonistic environment may develop a born poet who otherwise might have been dormant; but I will hazard the assertion that environment never made a poet out of material destined by the chromosomes for a brilliant career as hardware jobber.

CROP OF POETS NOT CONSTANT

So there is no reason for supposing that the crop of poets at Dartmouth, or anywhere else, should remain fairly constant from year to year. The big red team at Cornell seems, in retrospect, to have been a matter of Kaw and Pfann much more than of Gil Dobie. For a few years the fates sent to Cornell the nucleus of a great team; and the other men, average good players, were developed to the utmost by that environment of greatness. The same sort of situation obtains among the Dartmouth poets. Three or four unusally good undergraduate writers, in 1925 and again in 1930, spread the infectious desire and set the pace; in consequence, scores of students indulged an urge that might otherwise have gone unrealized; and of the scores, a dozen or so discovered in themselves powers that might never have been developed if they had attended college at a time when the fever was not in the air. There is no particular reason for hoping that the born, indubitable poet will appear in every Dartmouth class. It is much better, in fact, to have three or four at a time with dull periods intervening. The fates seem cognizant of that wisdom.

Such is the general status of poetry at Dartmouth from year to year. Let me now introduce you to some of the poets as personalities. The two whose pictures appear on this page I have chosen for emphasis not only because they were prize winners in the contest conducted by The Arts last February, but also because in subject matter and in vehicle of expression they represent opposite extremes.

Courtney Anderson is a senior, and seems to be a descendant of the same sort of Scandinavian-American stock that gave us Carl Sandburg. He probably will not thank me for comparing him to anyone except himself; but his verse seems to be heavily influenced by that older poet. It exhibits a kindred interest in rugged realities, an impatience with classical restrictions upon expression. It differs in that Anderson, whether he knows it or not, is much more interested than Sandburg in people as individuals. Chicago's poet sees them usually in the mass. Anderson picks them out and scrutinizes them one at a time, In his longer poems he attempts to take their minds to pieces, as one might a clock; and usually at some point he comes across an inscrutable fact confirming his original suspicion that

"People will not go in narrow tracks of print, in little black letters, in neat pagesPeople sprawl crazily on many pages, and skip, pages are missing, the words are mixed up, and all in a language and printing more complicated than any you can imagine. The books are too easy."

All this is expressive of Anderson's deep distrust of traditional methods, of pedantry, of the sort of scholarship that thinks it must perpetuate the attitudes of its elders, however much the world changes. Yet, most of his verse that I have seen concerns itself with very old people. There is one opus called Grandma, in which he addresses an old crone musing of the lusty lover of her youth, in Sweden, who knows how many years ago? There is another, called Old Man Johnson, which Anderson thinks his masterpiece, although no one will agree with him.

Just at present Anderson is a valiant and lone upholder of radical social theory in the college. There may be others, but they do not make themselves loudly articulate. His idol is Mike Gold, the combustible author and playright of The New Masses. Anderson used to maintain his hair in an involved state of disarray that must have been harder to achieve than any degree of elegance imaginable; but this sign of temperament has waned, and now he is much like the other Dartmouth poets in his general attitude toward personal appearance.

WHAT SHOULD A POET BE?

This is an attitude that I should like to stress in passing. The arty and the exotic do not seem to flourish in this hardy northland. There is little basis for thinking that poets must be the sturdy vagabond type, exemplified by our own Hovey; but there is even less basis for thinking that they must be the languid, half-mad creatures of popular tradition. Some of the treasured poetry in England's heritage has been written by cripples, dipsomaniacs, drug addicts, and the hopelessly diseased; but most of the best of it was written by men who, at the time they wrote it, were in perfectly good health and were maintaining positions of unspectacular esteem in their several communities. The latter state of affairs, both historically and at present, is true of Dartmouth's poets. Richard Hovey and Robert Frost, the two most famous names associated with the college, certainly indicate this; and such a recent example as Richard Eberhart '26, whose book, A Bravery of Earth, has been published both in England and in America, carried on the tradition by a trampfreighter vagabondage around the world, an experience which forms the basis for the best part of his long poem. So it is, too, among the undergraduate poets. As a group they dress and go about their business quite as if they were majoring in Eccy instead of taking English honors. I have yet to see the flowing bow tie of the Left Bank languishing upon a hollow Hanoverian chest.

It may be a sign of self-consciousness, and it may be entirely beside the point, so to rejoice over the appearance of Dartmouth's singers; but there is a real basis for my rejoicing. For one hundred years the whole realm of poetry has suffered from an aura of unconscionable nonsense fostered, no doubt with tongue firmly thrust in cheek, by the romantics of the early nineteenth century. They sweated and toiled and swore and erased and rewrote and polished their work, as poets have done from the beginning of time (the manuscripts prove it) and then amusingly gave it out that the poems so produced had come effortlessly from an ethereal muse, a cosmic reservoir, or an opium dream. Elinor Wylie, in one of her best essays, did a masterly job of puncturing such absurd notions of creative composition, using as an example her beloved Shelley, who was as guilty as anyone of starting the whole singular hoax. By the end of the century, despite the sturdy examples of Wordsworth, Tennyson, and Browning, poetry was almost laughed out of existence because of this curious attitude. Its friends stuck by it, but it was lost to the great masses; and to them it still is lost.

A POET MAY BE A GOOD FULLBACK

That is why I am happy to see, in Hanover, a whole group of poets—and very good poets, considering their youth—taking poetry seriously as a vocation or avocation, and even at a most impressionable age quite free from the onus of plush pants, long locks, and impassioned languor. From such beginnings a new race of poets may grow, worthy of the respect of the man who digs subways or potatoes. That is why it so deeply pleases me to find Kimball Flaccus, winner of first prize in The Art's competition, playing fullback on the varsity soccer team in his sophomore year.

It is a little surprising as well as pleasing, because Flaccus, in contrast with Anderson, writes an all but meticulous, a delicate style, entirely traditional, and concerned usually with beautiful and fragile things. I do not want you to misread that statement, because they are also deathless things: the legend of Queen Helen, flowers, beautiful dreams, and the tinsel remnants of mistaken loving. Purely as a technician, within his own deliberate concepts of technic, he is unquestionably the finest poet of the group. He is, in fact, more sure of his technic than any other modern poet of his age that I have ever known, or whose works I have ever read. That his themes are as yet the themes common to all sensitive youth, in its first awakening, is both healthy and inevitable. When the great and unique ideas come, he will be superbly ready for them. Mean while, at intervals of his soccer playing, he pauses to make out of toil and passion and scrupulous restraint such poems as this one:

LINES FOR A TOMBSTONEGolden as ever,The sunlight fallsJust as dancinglyDown old walls.Newts still drowseOn sun-warmed feet;Clambering rosesAre no less sweetThan ever they were,And breathlesslyThe slim new moonSteals wp the sky.But graves are astirWith night-black wings,So watch for meThese lovely things.

Between these extreme cases, between Anderson and Flaccus, are ranged a dozen or more others that I regret I have not space to talk about. My advice is that you make their acquaintance through their works, in Dartmouth Verse 19SO, which is, incidentally, one of the most beautifully- made books that I have seen in a long time.

COURTNEY ANDERSON '3l Apostle of modernism, who represents the left wing in Dartmouth's vigorous poetic renaissance. His poem, Advice toScholars, won third prize in The Arts contest for 1930.

KIMBALL FLACCTJS '33 Fullback on the varsity soccer team and traditionalist in his poetry, who won with a sequence of three sonnets the first prize in The Arts contest for 1930.

TheNorthlandTroubadours

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

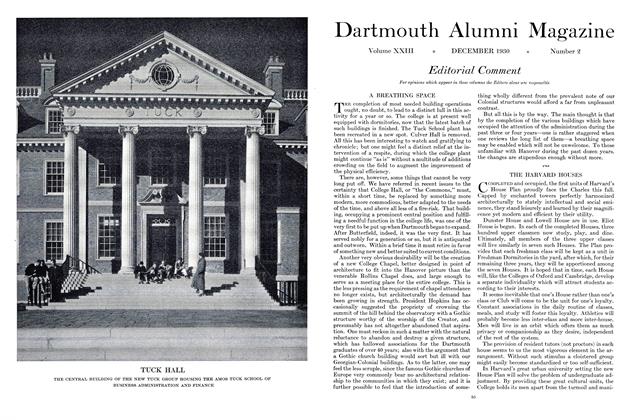

ArticleThe New Tuck School Plant

December 1930 By Dean William R. Gray -

Article

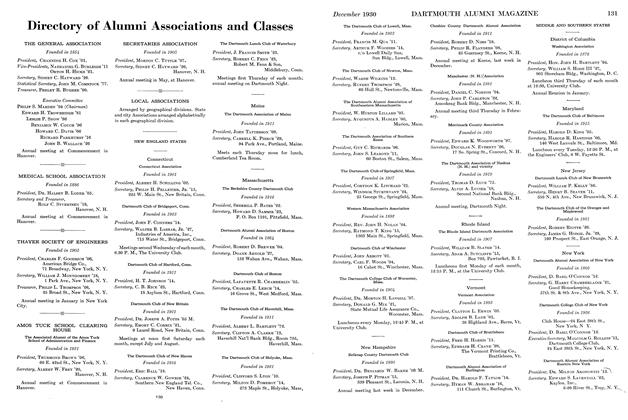

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

December 1930 -

Article

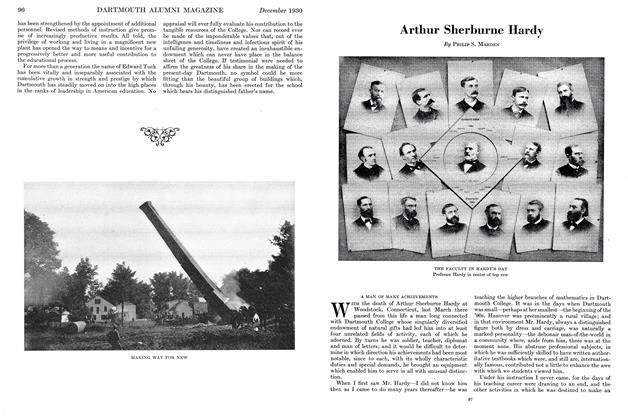

ArticleArthur Sherburne Hardy

December 1930 By Philip S. Marden -

Article

ArticleHarry Hillman: A Dartmouth Institution

December 1930 By Phil Sherman -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1930 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

December 1930 By Truman T. Metzel

Alexander Laing

Article

-

Article

ArticleGOLF

JULY 1967 -

Article

ArticleTwo Receive Alumni Awards

MAY 1971 -

Article

ArticlePumpkinfest

Jan/Feb 2011 -

Article

ArticleLandlocked Women Skippers Find Smooth Sailing

September 1995 By Brad Parks '96 -

Article

ArticleAstronomer Gary Wegner: Seeker of another world

DECEMBER • 1985 By Dave Coburn -

Article

ArticleCharles A. Proctor

November 1940 By JOHN HURD JR. '21