Conquering mountain peaks is fart of the work of theOuting Club, and the accomplishment at Moosilauke is thebeginning of the conquest of other mountains. Alumni whoare out-door minded will find a visit to Moosilauke a delightful experience in the summer or fall when the trails areeasy to follow.

FOR ten summer seasons the Dartmouth Outing Club has maintained open house on the summit of Mount Moosilauke. Last summer 2019 persons signed the log of the Summit Camp, thus indicating they had partaken of the hospitality of Dartmouth's famous outdoor organization. Some slept overnight in the snug Hudson's Bay Cos. four point blankets provided by the club, some satisfied the voracious appetites which only mountain climbing can develop, while others sought shelter and warmth within the summit house before attempting the descent. No matter what the duration of their stay, it is always evident that Moosilauke visitors linger longer than their itinerary intended.

Mount Moosilauke has, unfortunately, been too often described as a foothill of the White Mountains for this connotation underestimates its true size in the opinion of the initiated. For Moosilauke's altitude of 4811 feet above sea level ranks it among the higher peaks of the New Hampshire White Mountains. To be sure, it rises from comparatively low surrounding country and it is forty miles in an air line from Mount Washington, yet it cannot be classed as a lesser satellite.

Mount Moosilauke resembles a formidable outpost on the southwestern frontier of the mountain district. It stands a lone watch over the moat of the nearby Connecticut River toward the Green Mountains in the middle background and the highest peaks of the Adirondacks on the horizon.

From the summit of Moosilauke the peaks of all the New Hampshire mountain ranges maybe viewed in their proper perspective. The northeast quadrant is undoubtedly the most fascinating for successive loftier ranges appear in the line of vision toward Mount Washington, the highest peak of the Northeast. Modern set back skyscraper architecture might have found its inspiration in the terraced appearance of Washington's southern neighbors.

Mount Jim, a lesser peak of the Moosilauke mountain mass, rises in the immediate foreground. Where Moosilauke slopes cease, the ridges of Kinsman commence their upward sweep, and between dashes the popular Lost River. The great gash which the Franconia Notch cuts in the White Mountain landscape can be fully appreciated from Moosilauke for on the farther side of the notch the Franconia Range, with lofty Lafayette and slide-scarred peaks, occupies a predominant position in the vista. Behind this jagged range may be seen the mountains which border the vast Pemigewasset Wilderness. And in the far distance proud Washington pierces the skyline above the last buttress formed by the southern peaks of the Presidential Range.

The southeast quadrant offers a view wholly different but to many just as satisfying, for the great lake country of central New Hampshire is spread out so clearly that the indentations on the shore lines are easily discernible.

To the west may be found a panorama that is ideal for the diversified sunsets it helps to create. Under the shadow of the bulk of Moosilauke is seen the Benton Range, Moosilauke's own foothills. Then the Connecticut flood plain and all the prominent Vermont mountains occupy the background. The skyline peaks of Marcy, Maclntyre and Whiteface in New York State are often evident on the clearer days.

ORIGIN OF THE NAME

Moosilauke owes its name to at least two distinct and probably unrelated sources. One version has it that the mountain was first named Moosehillock because of the great numbers of moose which once ranged about its slopes. This story is given some credence by the statement of William Little, inimitable historian of the town of Warren, N. H., that Chase Whitcher once followed his hound on a moose hunt over the summit, thus becoming the first settler to stand on the peak.

The same hunter killed a caribou on Mount Carr, Moosilauke's nearest neighbor on the south, thereby winning for himself a second distinction, that of killing the one and only caribou ever shot in Warren. Many of the natives still refer to the mountain as Moosehillock.

Another derivation is from the Indian "Moosi" meaning "bald" and "Auke" signifying "place" with the "1" added for the sake of euphony. Moosilauke, to be sure, is somewhat of a "bald place" but there are many other New Hampshire mountains to which the name could be better applied, for the tree line of Moosilauke is comparatively high and erosion has not washed away the mineral soil found very near its highest point.

If the charter of the Moosilauk Mountain Road Company granted by the New Hampshire legislature is any criterion, the final "e" was dropped in spelling its legal name. Even at the present time, the more devoted of Moosilauke's converts are not content without using an additional "e," to form a fourth syllable.

FIRST ASCENT BY INDIAN

The legendary first ascent of Moosilauke is attributed to Waternomee, one of Wanalancet's subordinate leaders. This chief is said to have climbed the mountain with a small band en route to the "Quonnecticut" valley about 1700. According to the legend, "As they sat on the topmost peak, the wind was still, and they could hear the moose bellowing in the gorges below; could hear the wolf, Musquoshim, howling; and now and then the great war eagle, Kenau, screamed and hurtled through the air." The Indians gazed with superstitious reverence until late in the afternoon when a thunder storm accompanied by wind-lashed hail forced them into the shelter of the dense spruce. "It is Gitche Manito coming to his home angry," declared the chieftain as he led his band below tree line.

While returning with Robert Rogers' Rangers in the fall of 1769 from the attack on St. Francis, Robert Pomeroy of Derryfield (now Manchester) attempted a short cut home over the mountain with Benjamin Bradley of Rumford (now Concord). Bradley remarked, "In three days I'll be in my father's house," while leaving his comrades who were waiting at the confluence of the Ammonoosuc and Connecticut, where Woodsville now stands, until Rogers might return from Charlestown, N. H., with supplies.

The legendary account of this ill-fated short cut as narrated by William Little, the Warren historian, is an excellent example of the sort of tragic legend which is interwoven in the history of Moosilauke. "One night, when the rest of the band were asleep, they took from a knapsack a human head, cut off pieces, roasted them upon the coals, satisfied their hunger, and at the earliest dawn departed. Late in the afternoon they were standing upon the summit of Moosilauke mountain. They stopped to rest and to gaze upon the wildest scene that ever met their eyes. Mountains like mole-hills were scattered through the great north country. ... As the crescent moon, at first pale but with growing brightness, together with a single star of large magnitude, appeared over the summits of the snowy eastern mountains, Pomeroy, benumbed with cold, sank down saying he must sleep. . . . And when the last twilight had faded from the western sky he in turn sank down exhausted at the foot of the Seven Cascades." The fact that the bodies of these adventurers were later found and identified indicates that they perished under some such circumstance.

NOW AN OUTING CLUB TRAIL

But today the mountain is far more accessible than in Pomeroy's time for the trunk trail of the Dartmouth Outing Club trail system from Hanover to Littleton passes over the summit. Each summer two undergraduates patrol the trails replacing ladder rungs, chopping blowdowns and repairing waterbars.

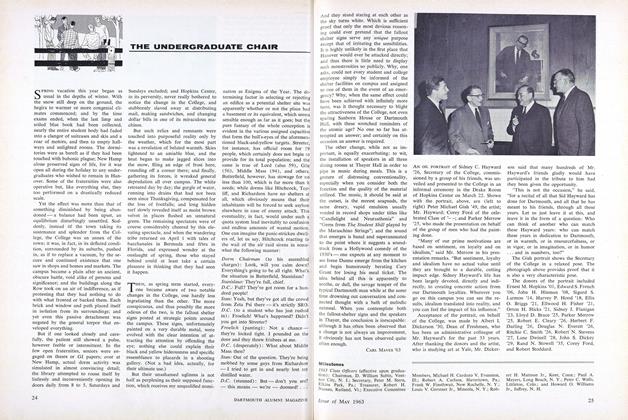

The best graded and most popular route to the summit is the Glencliff Trail, four miles in length, which leaves the Sanitorium Road north of Glencliff Village and ascends the mountain past the D. O. C. Great Bear Cabin to the South Peak where it joins the Carriage Road. This latter route is the original way by which the Warren settlers climbed to the Prospect House. It is famous for the number of "switchbacks" or acuteangled turns down which the undergraduates race on skis each winter in the Dartmouth Ski Championships.

A third path leaves Beaver Meadow at the height of land in Kinsman Notch, one half mile above Lost River, and boldly follows the Beaver Brook to its source high up on the mountain. This trail has the steepest grades for in some places ladders have been found necessary. A fourth and much easier route, the Benton Path, starts from the Parker House in Wildwood and climbs the northwestern shoulder.

These trails are all kept in order by the Outing Club which also has marked several alternate routes such as the Tunnel Road and the Breezy Point Trail to be followed in winter when storm conditions do not allow the skier to cross the exposed mountain crest in safety.

The original forebear of the present Moosilauke Summit Camp was built in 1860. This was a crude structure of stone named the Prospect House which old photographs depict as a sturdy one-story building with walls of stone three feet thick and wooden roof. This building consisted of a dining room, kitchen and a few sleeping rooms. The shingles were hand riven on the mountain slopes and the rest of the building materials were hauled up the newly completed Carriage Road by an ambitious group of natives. Two yoke of oxen were used for a whole month and the builders camped at Cold Spring, a mile from the mountain top.

The building was dedicated July 4, 1860, with all the attendant pomp and show that marked celebrations of that period. Two horses attached to a large pleasure wagon were driven up the mountain side. It is said that more than a thousand people were present for the ceremony. The Newbury brass band furnished the music while a regiment of citizens marched and countermarched on the rocky summit under Col. Stevens M. Dow.

_ The Honorable Thomas J. Smith delivered the traditional patriotic oration of that period after which a party of genuine Indians concluded the services with dancing, singing and war whoops. War whoops are still heard on Moosilauke's summit but they are of the Wah Who Wah dialect shouted by the Dartmouth undergraduate occupants in welcoming or bidding farewell to visitors.

Although William Little was the first landlord of the Prospect House, James Clement enjoyed the longest term in that capacity. As a thoughtful and accommodating host Clement established the tradition which the Dartmouth Outing Club has succeeded in retaining.

In 1872 a story and a half addition of wood was erected containing the office, parlor and other sleeping rooms. Occasional alterations since then, notably in 1881 when a wooden superstructure was added to the original stone house, have formed a summit house so large that its shape is a very distinct landmark on the skyline as seen from the Connecticut Valley.

PRESIDENT GARFIELD A VISITOR

The summit has been visited by climbers of all types. President Garfield was entertained there during the summer of his presidential campaign. The register of the Prospect House under the date of August 29, 1860, records, "Philip Hadley, 90 years old, came up to the Prospect House. He lives at Bradford, Vt., and he walked all the way from that place to the top of the mountain."

In 1869, James Cutting, 85 years of age, rode horseback from his home in Haverhill, N. H., to the top and back in the same day. In later years a veteran mountain-climbing Ford is said to have negotiated the sharp turns and steep grades of the Carriage Road, a feat that would compare favorably with any record ascent of Pikes Peak.

The Prospect House was occupied by J. H. Huntington and A. F. Clough during the months of January and February, 1870, to demonstrate the possibility of living on a mountain top prior to the proposed occupation of Mount Washington the following winter. These two men busied themselves with scientific observations and were rewarded by recording a wind velocity with their anemometer of ninety-seven and a half miles an hour, the greatest ever recorded up to that time. This record was broken in January, 1877, on Mount Washington when a velocity of 186 miles per hour was recorded on accurate scientific instruments by the U. S. Signal Service observers.

After a long period of prosperity the interest in mountain top hotels began to wane and subsequently the property was no longer occupied by a caretaker.

A " O X t/ vwiVVMixvVAs But in 1920 a new era commenced when the buildings and a small circular tract of land were given the Dartmouth Outing Club by E. K. Woodworth and Charles Woodworth of Concord, N. H., themselves Dartmouth alumni. The wish of the donors that the summit house be operated as a shelter and accommodation for trampers has been fulfilled by the club. Undergraduate members at once set to work with the advice of faculty members repairing the building so that it might once again be used as a mountain top shelter.

The thick iron rods which anchored the building to the summit ledge were the first consideration. Five heavy braces were found attached to the west-wing, entering the building about two feet above the ceiling of the living room. Another similar brace served to hold down the wooden superstructure in the northwest corner of the main building. Two more rods running north and south kept the walls of the living room square.

The turnbuckles of these re-enforcing braces were tightened with considerable difficulty in 1920 and replaced throughout the building in 1927. During the twoday period when the old braces were slack while the new ones were being installed a typical September "blow" out of the northwest severely taxed the strength of the unsupported walls. It was with a feeling of intense relief that the new turnbuckles were finally adjusted.

Each succeeding summer has seen some additional major improvement. The early caretakers were kept busy reshingling roofs, replacing sills and painting both exterior and interior woodwork. In 1927 a fireplace was built for which fuel is cut on the National Forest land below tree line.

BUILDING A WINTER CABIN

In 1928 the old barn was demolished and on its site was constructed a Winter Cabin, built and used exclusively for winter occupancy by the club members. This past summer a telephone line was strung from Glencliff. The summit camp is now rated as a secondary fire look-out station in the U. S. Forest Service fire preparedness organization for much of the forest seen from the top belongs to Uncle Sam.

The summit camp is manned by a crew of four undergraduates whose versatility is tested frequently as the season progresses. The Camp is open from the middle of June to the middle of September.

The caretakers pack all their fresh supplies up the Glencliff Trail and the remaining foot, fuel and equipment is hauled up the carriage road by buckboard in quarter-ton consignments. This past summer three tons were landed on the summit by this method. All the food and equipment from kerosene oil to yeast cakes must be packed up the mountain on human backs or be hauled by the none too willing team of horses. Cranberry sauce is the one exception for on the grassy upland slopes are found mountain cranberries in abundance.

The Prospect House in days of yore was supplied with fresh milk from cows which grazed on wiry grass and Greenland sandwort. Each modern crew of caretakers threatens to lure a milch goat to the summit but at present evaporated milk and klim are used as substitutes for fresh milk.

Eight 55-gallon drums of kerosene oil were used during the past season for heating and cooking purposes. Boys and girls camps to the number of 79 visited the Summit Camp. According to the season's records, 14 Moosilauke pancakes were devoured by one of the camp boys at a single sitting. The capacity of the hungriest girl camper proved to be nine of the famous mountain griddle cakes.

Although the Camp is equipped to accommodate 71 overnight lodgers, 108 trampers were put up the night of July 30, the same day the supposedly reliable spring went dry thus necessitating a water haul of over a half mile. The record number taken care of any one night was established in 1923 when 147 climbers found protection under the roof of the Summit Camp.

When Mrs. Daniel Patch, the first white woman to stand on the summit, made her famous climb she carried with her a tea-pot in which she brewed tea over a fire kindled with the stunted alpine vegetation. Now the Summit Camp supplies so many wants that many climbers make the ascent burdened to the extent of a tooth brush.

The changes to be wrought on Moosilauke during its second decade under the stewardship of the Outing Club are the cause of much conjecture. A native of Warren has exhibited his air-mindedness by suggesting that the comparatively flat, plateau-like summit be capitalized by the construction of an airport but the club has other, more practical problems to solve first.

The summits of Lafayette, Moriah, Chocorua, Northern Kearsarge, Washington and Moosilauke have all been marked by buildings for the protection of the tramper but now only the two last remain intact. It is to be hoped that the elements will continue to regard the summit, of Moosilauke with the reverence shown toward the mountain by the Pemigewassets and the Pennacooks.

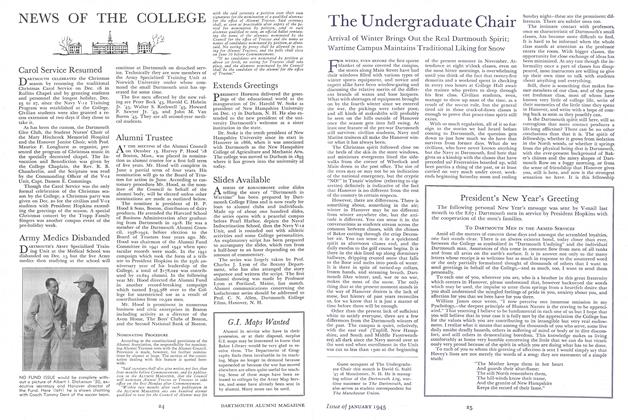

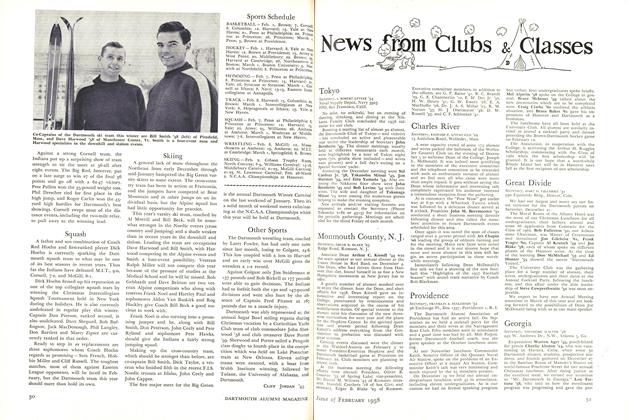

A WATER-CARRYING YOKE Armine Laughton '31 brings in a supply before the spring dries.

BASEBALL AT 4,800 FEET

SUMMIT CAMP

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleIndian Oratory

January 1930 By Jason Almus Russell -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

January 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA LETTER FROM ED STOCKER

January 1930 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

January 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1919

January 1930 By James Corliss Davis -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

January 1930 By Frederick W. Andres