Ask somebody in Hanover about South Africa, and he might launch into a tirade against Dartmouth investments in corporations doing business there. Or he might defend these companies as the only hope for change. But most likely he'd stare back blankly and shrug. The problem is that, despite increased publicity from both sides over the last year, the average person remains confused about a confusing issue. Adding to the bafflement is that all those concerned begin at the same point, a condemnation of the apartheid system, but split in opposite directions from there.

On one side stands American business. Over 300 U.S. companies have subsidiaries in South Africa, while thousands operate on an agency basis; dozens of banks provide indirect economic support through loans and trade credits. These investments, though small compared with the total economy, are concentrated in a few key areas such as automobiles, petroleum, and computers.

Most of these corporations feel they can best bring about change in the plight of the black South African by working from within. They claim economic sanctions or a U.S. withdrawal would further isolate the government, making it even less responsive to outside pressure for reform. A foreign power less interested in human rights might also move in to fill the created gap. Instead, a number of companies have endorsed the so-called "Sullivan Principles" a set of guidelines proposing racial equality in all employment practices, extra training for blacks, and efforts to improve the overall quality of life outside the work environment.

The opposition, concentrated at Dartmouth in the Upper Valley Committee for a Free Southern Africa, disagrees with this approach. They point out that U.S. business employs only 70,000 of the black work force of seven million. Even if these corporations adhered fully to the Sullivan Principles, the ultimate effect on the vast majority of workers would be negligible. Rather than reforming apartheid, members of the opposition would prefer to dismantle it. They theorize that, as long as the South African economy remains stable, the government will remain strong enough to impose the will of the white minority onto the black majority. U.S. withdrawal coupled with a complete economic embargo could result in one of several solutions. Ideally, the government would be forced to negotiate a peaceful transition to a one person/one vote rule. The possibility of a violent overthrow of the weakened Vorster regime by the already operative black guerrilla units also exists.

The College faces a similar question of "stay in or pull out?" concerning its stocks in companies continuing South African business. Those calling for continued American involvement naturally urge Dartmouth to retain its investments. Again the hope is to work from within, this time as a shareholder urging a corporation toward endorsement and full compliance with the spirit of the Sullivan Principles.

Those calling for withdrawal would like to see Dartmouth sever its ties with those concerns refusing to sever their own ties with South Africa. Such an act would serve mainly a political purpose through the generated publicity, besides ending what they term "Dartmouth's partnership in apartheid."

Precedent has already been set for educational divestment by a handful of institutions including the University of Massachusetts and Hampshire College. But according to Paul Paganucci '53, Dartmouth's vice president in charge of investments, the dollar value of the divested stock at those institutions doesn't approach the amount in question here. As of September, Dartmouth owned over $27 million worth of equities - almost 30 percent of its stock holdings - in companies described as having "substantial" South African investments. This figure does not include bonds. Assuming suitable alternate investments could be found, which Paganucci doubts, the "round-trip" costs between divestment and reinvestment would be around $1 million.

At their meeting in February of this year, the Trustees endorsed the Sullivan Principles and voted to "review the propriety of continuing an investor relationship with any corporation that fails to demonstrate adequate initiative in implementing" the guidelines. Since that time, the Upper Valley committee has lobbied directly with the Trustees and indirectly through the lower-level Advisory Committee on Investor Responsibility to have that resolution significantly strengthened. Since the Medical School problems preempted most of the time at the Trustees' November meeting, the earliest any change in policy could occur is at the next session in February. In the meanwhile, as the pro-divestiture groups pass out more literature and the College analyzes its position, perhaps we'll have fewer blank stares.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCrime and Punishment

December 1978 By Tim Taylor -

Feature

Feature'Raucous behavior of a different sort'

December 1978 By Mary Ross -

Feature

FeatureParadise Lost or Paradise Regained?

December 1978 -

Feature

FeatureGOOD NEWS

December 1978 -

Article

Article'Most Improved Professor'

December 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Article

ArticleStraight Shooter

December 1978 By D.M.N.

Article

-

Article

ArticleADDITIONS TO THE ROLL OF HONOR

May, 1914 -

Article

ArticleTHAYER SCHOOL BANQUET AT MOOSE MOUNTAIN CABIN

April, 1922 -

Article

ArticlePresident's Addresses

June 1931 -

Article

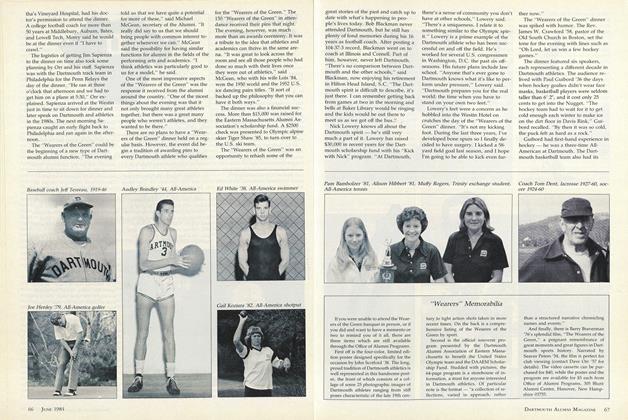

Article"Wearers" Memorabilia

JUNE/JULY 1984 -

Article

ArticleSCOREBOARD

December 1990 By Jonathan Douglas ’92 -

Article

ArticleNow Comes the Tug

June 1945 By P. S. M.