The Department of Public Speaking

To a college such as Dartmouth which has sent out somany men to join the legal profession, a college which possesses such a quantity of legal tradition, public speakinghas always been a much-prized curriculum asset. Butwith the decline of old-time oratory and old-time rhetoricalflourishes there came some years ago a falling off in interestin public speaking as such. But the revival in interest inthis subject has come with the needs of the modern world,among which is the demand for the ability which enables aman to stand on his feet and express himself in public.The ability to do this is a rather rare treasure.

THERE have been times in the history of education when public speaking, or rhetoric as it was called, has been the whole curriculum. There have been other times when the subject has been wholly neglected or, as elocution or declamation, has been relegated to a decidedly minor role among the academic disciplines. At the present time a reasonable mean seems to have been attained, with departments of public speaking or of speech in most of the colleges and universities of this country. Training in public speaking, once universally accorded the highest praise and again as universally despised, is now occasionally condemned as positively pernicious, but it is rather more frequently acclaimed as invaluable. A large majority of business and professional men, graduates of liberal colleges, have found at least some value in the cultivation of the art.

"Public" speaking does not mean oratory in the grand sense; there is no attempt in the department at Dartmouth to train nor any expectation of producing orators. The desirability of developing orators may be questioned, the impossibility is almost beyond question. It may be, as is so often said, that the relative importance of the orator has diminished in modern life; but there never was a time when men came together so frequently for discussion of common interests, in all sorts of associations, from Rotary clubs to academic conventions. And there never was a time before when the man of affairs found it so much to his advantage to be able to express himself in an effective manner. Luxuriant adornation and emotionalism do not indeed generally meet with approval outside of legislative halls; the temper of the age demands, for the most and best part although there may seem to be many exceptions, straightforward, business-like talking.

An effort is made in all the practical speaking courses of the department, in conferences and in the classroom, to teach students to get their ideas and facts in order and to present them simply, clearly, directly, and persuasively. "Persuasively" includes the other desiderata and something more. By and large the speech is to be distinguished from other forms of literature not so much by its being spoken as by its relation to the audience. In speaking it is always the particular audience, large or small, that must be kept in mind. It is necessary to con- sider the capacities of audiences, their interests, beliefs, and ways of reacting, how they can be made to under- stand, how their attention can be gained and held. This requires a study of human nature in its general and par- ticular manifestations, a sort of practical logic and psychology. The audiences considered range in size from small groups such as committees and boards of directors to the "millions of radio listeners." While there is no attempt to teach conversation as such, the training given has its application to the least public forms of dis- course, and has even been said by young graduates to have been of help to them in selling bonds. One of the by-products of the practice is that which comes from the necessity of the student's getting off the small of his back, out of the too common attitude of passive resist- ance, when he has to take a position in front of a real classroom audience and assert himself in an effort to make an explanation clear or an argument convincing.

The development in the student of a critical faculty, which will help him to distinguish what is sound from what is spurious in the arguments and speeches that will be addressed to him, should be mentioned. Bishop Whately has said : "This is indeed one great recommen- dation of the study of Rhetoric, that it furnishes the most effectual antidote against deception [by rhetorical tricks]."

It is more difficult to explain the cultural aspects of tlie study of a practical art having no definite body of knowledge as its field. There is, for one thing, the understanding of men and motives as that understanding arises from the practical training already mentioned. The course in Reading is not given with the hope of training public readers, but because ability to read well is an asset to any man and because oral reading provides an excellent method of gaining and testing literary appreciation. Somewhat different, although by no means independent, is the study of the literature of public address. Some speeches, and editorials and essays that are essentially equivalent to speeches, are studied in those courses where the chief emphasis is on practice. A more thorough study of the types of speeches is made in Advanced Public Speaking. The courses in Rhetorical Criticism and Classical, British, and American Oratory are primarily concerned with a critical study of the literature of oratory, a much neglected literature which contains many works that have exerted a significant influence on the affairs of the world.

There is being offered in the second semester of this year a new course in Legal Oratory, which is expected to be of value to students who intend to study law, although it is in no sense a "law course." British and American oratory, now included in part in the seminar, will become separate courses next year, when the department will again offer a major.

There are at present no courses in voice training or phonetics or "speech science" as such, although voice training is given some attention in the course in reading and incidentally elsewhere. Nor is there any organized work in speech correction. An attempt is made to improve the enunciation of students, to remove noticeable defects of enunciation and pronunciation, or at least to call attention to the defects. The use of a machine that records speeches and reproduces them with adequate fidelity, the Telegraphone, enables students to hear themselves as others hear them. Perhaps this laboratory should be further developed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

February 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

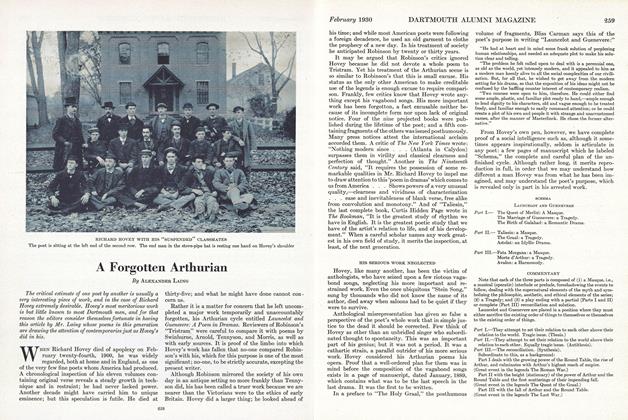

ArticleA Forgotten Arthurian

February 1930 By Alexander Laing -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1930 -

Sports

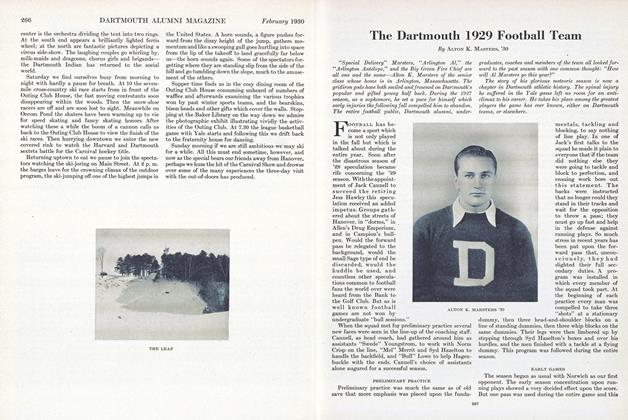

SportsThe Dartmouth 1929 Football Team

February 1930 By Alton K. Masters, '30 -

Article

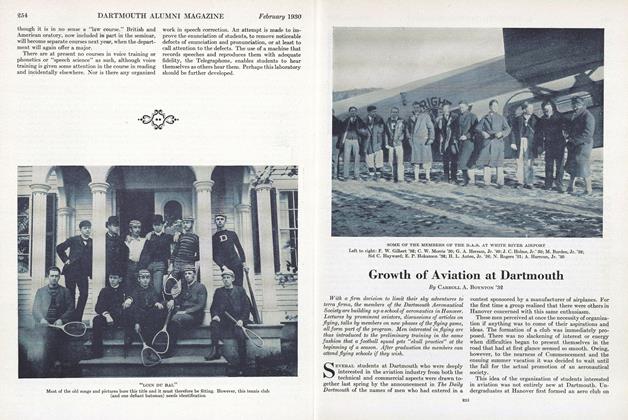

ArticleGrowth of Aviation at Dartmouth

February 1930 By Carroll A. Boynton '32 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

February 1930 By Frederick W. Andres

Article

-

Article

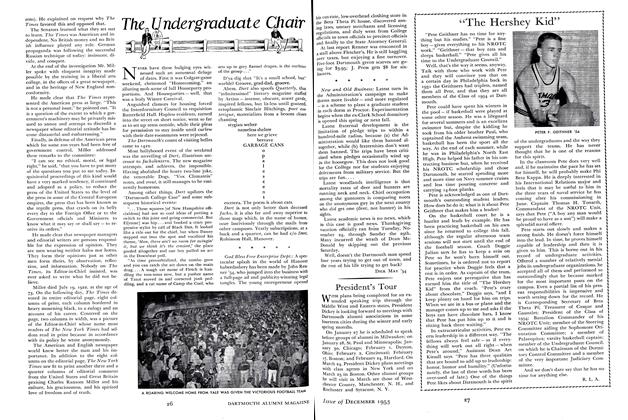

ArticlePresident's Tour

December 1953 -

Article

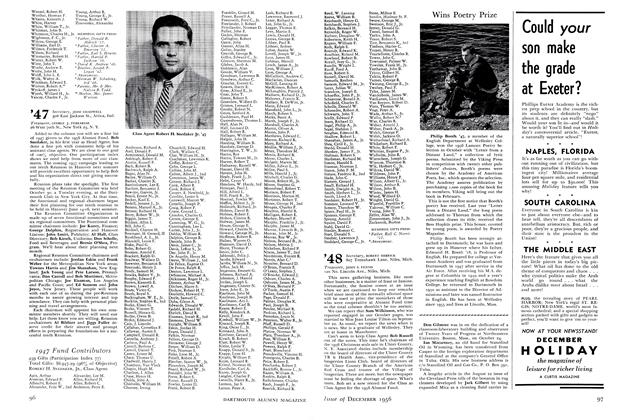

ArticleWins Poetry Prize

December 1956 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Delegates

MAY 1968 -

Article

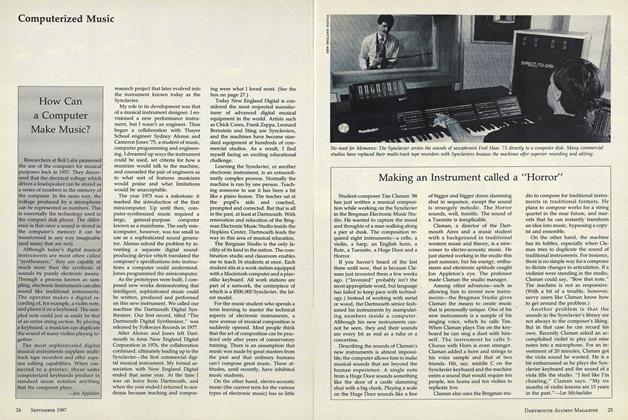

ArticleHow Can a Computer Make Music?

SEPTEMBER 1987 By Jon Appleton -

Article

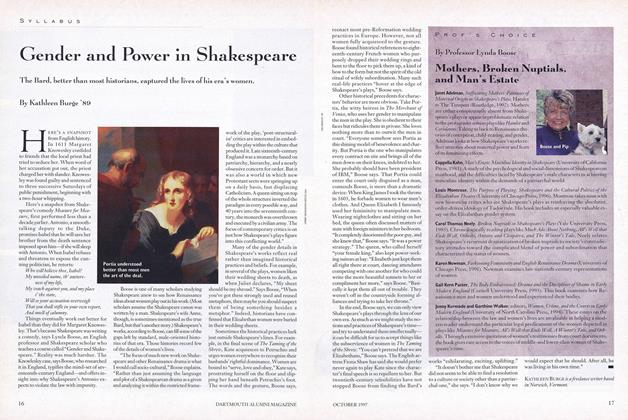

ArticleGender and Power in Shakespeare

OCTOBER 1997 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleRush Takes Its Time

December 1992 By Ross NOVA '94