The Bard, better than most historians, captured the lives of his era's women.

HERE'S A SNAPSHOT from English history. In 1611 Margaret Knowesley confided to friends that the local priest had tried to seduce her. When word of her accusation got out, the priest charged her with slander. Knowesley was found guilty and sentenced to three successive Saturdays of public punishment, beginning with a two-hour whipping.

Here's a snapshot from Shakespeare's comedy Measure for Measure, first performed less than a decade.earlier. Antonio, a smooth- talking deputy to the Duke, promises Isabel that he will save her brother from the death sentence imposed upon him—if she will sleep with Antonio. When Isabel refuses and threatens to expose the cunning politician, he retorts:

Who will believe thee, Isabel?My unsoiled name, th' austereness of my life,My vouch againsty on, and my placei' the state.Will so your accusation overweighThat you shall stifle in your own report,And smell of calumny.

Things eventually work out better for Isabel than they did for Margaret Knowesley. That's because Shakespeare was writing a comedy, says Lynda Boose, an English professor and Shakespeare scholar who teaches a course called "Gender and Shakespeare." Reality was much harsher. The Knowlesley case, says Boose, who researched it in England, typifies the mind-set of seventeenth-century England—and offers insight into why Shakespeare's Antonio expects to violate the law with impunity.

Boose is one of many scholars studying Shakespeare anew to see how Renaissance ideas about women play out in his work. (Most scholars assume the Shakespeare canon was written by a man. Shakespeare's wife Anne, though, is sometimes mentioned as the true Bard, but that's another story.) Shakespeare's works, according to Boose, can fill some of the gaps left by standard, male-oriented histories of that era. Those histories record few of the details of women's lives.

"The focus of much new work on Shakespeare and other Renaissance drama is what I would call socio-cultural," Boose explains. "Rather than just assuming the language and plot of a Shakespearean drama as a given and analyzing it within the restricted framework of the play, 'post-structuralist' critics are interested in embedding the play within the culture that produced it. Late sixteenth-century England was a monarchy based on patriarchy, hierarchy, and a nearly obsessive concern for order. But it was also a world in which new

Protestant sects were springing up on a daily basis, fast displacing Catholicism. A queen sitting on top of the whole structure inverted the paradigm in every possible way, and 40 years into the seventeenth century, the monarch was overthrown and executed by a civilian army. The focus of contemporary critics is on just how Shakespeare's plays figure into this conflicting world."

Many of the gender details in Shakespeare's works reflect real rather than imagined historical practices and beliefs. For example, in several of the plays, women liken their wedding sheets to death, as

when Juliet declares, "My sheet should be my shroud." Says Boose, "When you've got these strongly used and reused metaphors, then maybe you should suspect them of being something besides a metaphor." Indeed, historians have confirmed that Elizabethan women were buried in their wedding sheets.

Sometimes the historical practices lurk just outside Shakespeare's lines. For example, in the final scene of The Taming of theShrew, Kate acquiesces to Petruchio and urges women everywhere to recognize their husbands' rightful dominance. Women are bound to "serve, love and obey," Kate says, prostrating herself on the floor and slipping her hand beneath Petruchio's foot. The words and the gesture, Boose says, reenact most pre-Reformation wedding practices in Europe. However, not all women fully acquiesced to the gesture. Boose found historical references to eighteenth-century French women who purposely dropped their wedding rings and bent to the floor to pick them up, a kind of bow to the form but not the spirit of the old ritual of wifely subordination. Many such real-life practices "hover at the edge of Shakespeare's plays," Boose says.

Other historical precedents for characters' behavior are more obvious. Take Portia, the witty heiress in The Merchant ofVenice, who uses her gender to manipulate the men in die play. She is obedient to their faces but ridicules them in private. She loves nothing more than to outwit the men in court. "Everyone somehow sees Portia as this shining model of benevolence and charity. But Portia is the one who manipulates every contract on site and brings all of the men down on their knees, indebted to her. She probably should have been president of IBM," Boose says. That Portia could enter the court only disguised as a man, contends Boose, is more than a dramatic device: When King James I took the throne in 1603, he forbade women to wear men's clothes. And Queen Elizabeth I famously used her femininity to manipulate men. Wearing night clothes and sitting on her bed, the queen often discussed matters of state with foreign ministers in her bedroom. "It completely disoriented the poor guy, and she knew that," Boose says. "It was a power strategy." The queen, who called herself "your female king," also kept power-seeking suitors at bay. "Elizabeth just kept them all right there at court, dancing attendants competing with one another for who could write the more beautiful sonnets to her or compliment her more," says Boose. "Basically it kept them all out of trouble. They weren't off in the countryside forming alliances and trying to take her throne."

In the end, Boose says, we can only view Shakespeare's plays through the lens of our own era. As much as we might study the notions and practices of Shakespeare's time- and try to understand them intellectually— it can be difficult for us to accept things like the subservience of women in The Tamingof the Shrew. "You can't pretend that we are Elizabethans," Boose says. The English actress Fiona Shaw has said she would prefer never again to play Kate since the character's final speech is so repellent to her. But twentieth-century sensibilities have not stopped Boose from finding the Bard's works "exhilarating, exciting, uplifting." "It doesn't bother me that Shakespeare did not seem to be able to find a resolution to a culture or society other than a patriarchal one," she says. "I don't know why we would expect that he should. After all, he was living in his own time."

Portia understood better than most men the art of the deal.

KATHLEEN BURGE is a freelance writer basedin Norwich, Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

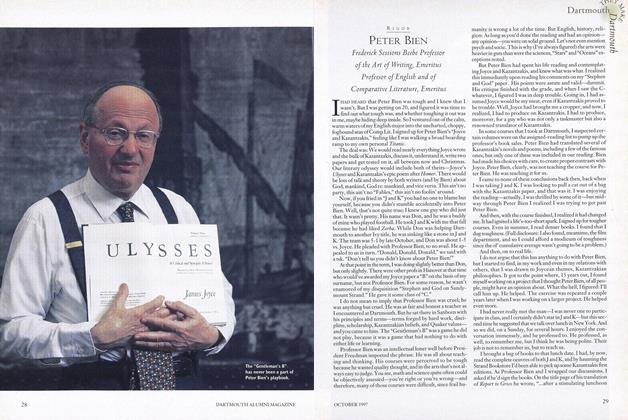

Cover StoryPeter Bien

October 1997 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryM. Lee Pelton

October 1997 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMarysa Navarro-Aranguren

October 1997 By Holly Sorensen '86 -

Cover Story

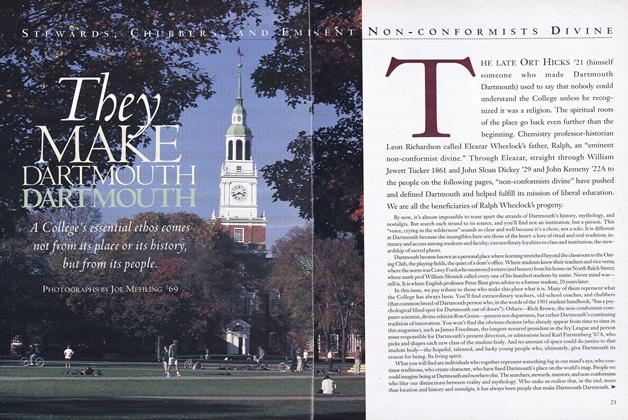

Cover StoryThey Make Dartmouth Dartmouth

October 1997 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWilliam Cook

October 1997 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChris Miller '97

October 1997 By Jake Tapper ’91

Kathleen Burge '89

-

Article

ArticleWhen Bad Things Happen

January 1996 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleOne for the Road

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleWhat Beethoven Heard

NOVEMBER 1996 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleNovels that Came in from the Cold

APRIL 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleThe Origin of Endangered Species

SEPTEMBER 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleMother Russia's Daughters

DECEMBER 1999 By Kathleen Burge '89