Executive Secretary, The Business Historical Society

OF the thousands who know John James Audubon as a naturalist and painter, very few, probably, think of him as a successful business man. Indeed, to those who knew him in his youth, such a description of him would have seemed like a contradiction in terms. Nevertheless, the same impractical, restless young man who appeared to have an uncanny ability to make a failure of the most promising commercial enterprise performed, in later life, a feat of salesmanship which would rival the best that the twentieth century has to show. This was the well nigh impossible task of marketing in England his Birds of America, a work in double elephant folio, containing more than four hundred plates of life-sized birds, all hand colored, and costing a thousand dollars.

An achievement hardly less remarkable was the selling of an octavo edition of the Birds in the United States, at a period in the cultural and economic life of this country when a hundred-dollar work on natural history would normally have had no place in any family budget. A diary of Audubon's, kept during his canvassing trips in the eastern states and Canada from 1840 to 1843, has recently been published through the joint efforts of the Club of Odd Volumes, of Boston, and the Business Historical Society, Inc., in an edition limited to the memberships of the two organizations. This book is the second publication in which The Business Historical Society has participated. The material for the book, on deposit with the Society, is one of two diaries of his in existence, and is now published for the first time. It is one item in a remarkable collection that is being brought together by a group of men including some of the leaders in both business and academic fields. They have undertaken to recreate from old records, which have been passed over as valueless or merely curious, the commercial background of modern civilization, a feature of history which has been too long neglected.

Francis H. Herrick, in a foreword to the volume, says: "It represents but a small part of that rapid journalizing by which Audubon, when from home, was wont to record his daily experiences. . . . It is enough, however, to show his indefatigable industry, his singleness of purpose and his kindness of heart."

One might add his unquenchable "joie de vivre." His comments on the prospects in the various cities he visits show a humorous view of the obstacles he finds in his way, combined with a persistence and determination which surmount the most difficult of them. At Worcester, Audubon says:

"Called after Tea on Mr. Harris, The Bookseller, who told me that I must not expect more than one or two subscribers here. Nous Verrons, Monsieur Harris."

Three days later, he writes: "Sent my letter (written yesterday) home with 18 names procured here."

THE WEBSTER INCIDENT

He finds Providence pleasant, even though unprofitable. It is full of fine people, says he, but they do not study ornithology. At Duxbury he met the "wife of a Physician whom I found both handsome and amiable. She is well acquainted with Dl Webster, where she has seen my great work several times, but she not knowing Mr. W. as well as I do called the Volumes there his Copy??? When paid for! tomorrow I proceed to Ingham without calling at the house of Mr. Webster although his residence? is only 3 Miles from this."

He ends this entry with characteristic expressions of affection for the family to which he seems to have re- mained devoted throughout his wandering life:

"I am now at the Tavern of Mr. W. W. Winslow, w'l enough in all Conscience. Good Night Love and God bless you all."

The conclusion of the Daniel Webster incident comes later in the book. He writes from Washington, with an exclamation mark, that he called on Mr. Webster who gave him a check for $100 on account, remarking that "Mr. W. would give me a fat place was I willing to have one; but I love indipendence and piece more than humbug and money!"

By dint of several more calls, he finally collected the whole amount.

In Portsmouth, New Hampshire, he writes forgivingly:

"If tomorrow is not better than today, I shall not as Wilson did Louisville, damn Portsmouth, but bid it my adieus."

Again and again, entries begin, "I was up at 4 this morning." On the coach for Hingham, making an early start from Duxbury, his "companions . . . were only 2 of both sex and extremely talkative;—Poor (?) I took Snuff and gazed on the Nature spread around me."

His unwearied interest in places and people, and his sprightly comments make every page of the diary entertaining reading, while throughout are felt the wholeheartedness, charm, and confidence which explain his accomplishment of his apparently hopeless undertaking. When he finally threw aside conventionalities and wellmeant advice to follow his real talent, the instinct which he had followed blindly through a maze of commercial failures welded what had seemed a singularly futile, though lovable, collection of qualities into the elements of his amazing success.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

February 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

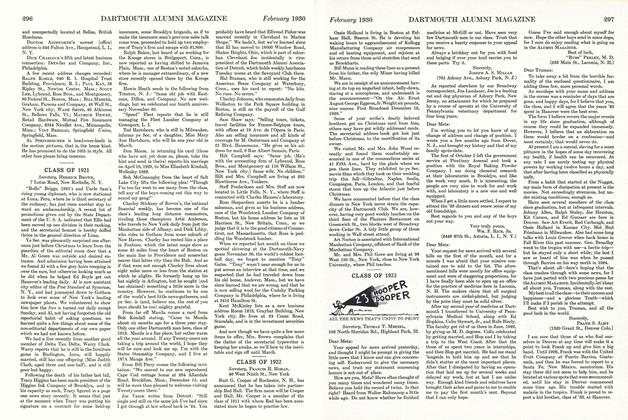

ArticleA Forgotten Arthurian

February 1930 By Alexander Laing -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1930 -

Sports

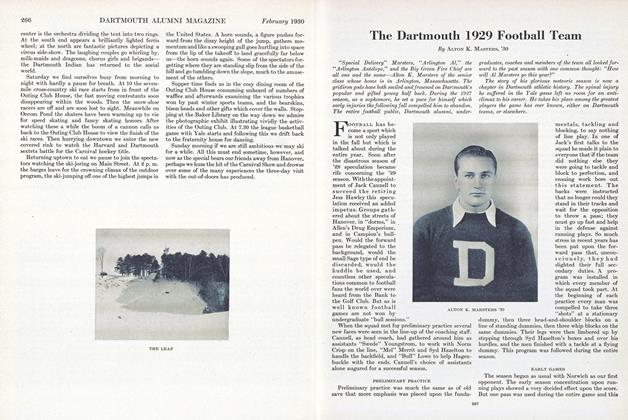

SportsThe Dartmouth 1929 Football Team

February 1930 By Alton K. Masters, '30 -

Article

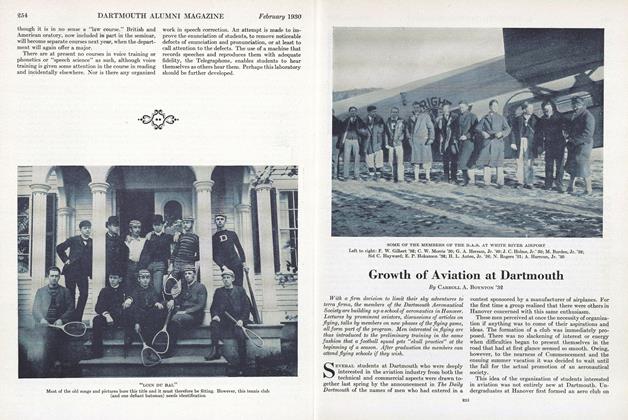

ArticleGrowth of Aviation at Dartmouth

February 1930 By Carroll A. Boynton '32 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

February 1930 By Frederick W. Andres

Article

-

Article

ArticleLIBERAL CLUB TO BRING SPEAKERS TO HANOVER

November 1921 -

Article

ArticleGRIDIRON GROPINGS

November 1935 -

Article

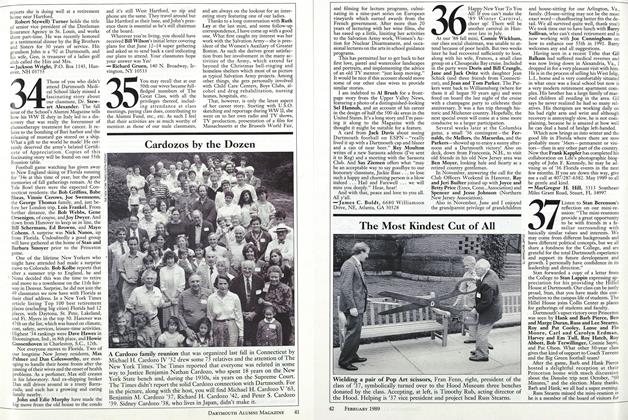

ArticleCardozos by the Dozen

FEBRUARY 1989 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1956 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleREPORT FROM THE COUNCIL

FEBRUARY 1989 By Patsy Fisher-Harris '81 -

Article

ArticleHartford

MARCH 1968 By ROBERT B. FOSTER '48, DICK WATSON '59