A friend and former student of mine who is an M.D. in Florida has sent me a copy of a paper by the Chancellor of the University of Kansas which was read at a meeting of the A.M.A. Council on Medical Education and Hospitals in Chicago last year. The particular session at which the paper was read, believe it or not, was listed as "The Town and Gown Syndrome" and this particular paper bore that title followed by the qualifying word "Pathology." It dealt in general with the conflict of interests between those who push highly specialized medical teaching and research and those who spend their efforts in the day-to-day practice of medicine—an interesting topic which need not detain us here. It is only the application of the "town and gown" figure of speech and the use of the term syndrome" which interests the writer of this old-fashioned "Town and Gown column.

Syndrome is one of those new words which leaves me floundering. I have on my desk a cherished copy of Webster'sCollegiate Dictionary which contains no sign of this high-sounding word, evidently concocted from the Greek. The old dictionary was given to me with expressions of gratitude and affection on my first teaching assignment 44 years ago, and has served me long and well, but now, alas, I find those happy days were pre-syndromic. The world has grown more diagnostic and in the latest edition of Webster's Collegiate I find syndrome defined as "a group of signs and symptoms that occur together and characterize a particular abnormality." I am sure the medics were correct in bringing in the town and gown allusion for this business of the accretion of new words which are a concomitant of our increasingly technical and scientific age is part of the whole problem of town and gown.

I suppose faculty folk were always given to the use of $64 words - sometimes quite esoteric ones - but in the old days the town usually took their use as an academic joke and laughed about it. Now somehow the situation is different and language and terminology have become if not an iron at least a bamboo curtain between town and gown. What was laughed off as "pedagese" now becomes a more serious barrier.

One can more easily understand the introduction of new terms to accompany the nuclear scientific age which bestrides us like a colossus, but this business of a technical lingo or jargon has spread abroad and has crept over into the social sciences as well. History, which some historians believe should not be classified as a social science at all, has remained singularly old-fashioned and clear in the use of language, but psychology and sociology and economics have certainly fallen prey to a semi-private terminology in which one must be initiated if he is to understand. To take the relatively simple developments in economics, one must realize that no economic research problem these days is worth its salt if it does not require extensive use of computers. The simple days of "diminishing returns" have given way, under strong mathematical influences, to "multipliers" and accelerators" and "demand functions" and "function coefficients."

To be perfectly honest, it is not the townsmen alone who sometimes find communication difficult in discussing some of these problems. An older member of the faculty, from the humanities for example, may get into a discussion with a young economist on some question of governmental finance and be told that argument is fruitless until he understands the new terminology. Gone are the simple days when a distinguished social scientist would say to a graduate student in a seminar, "If you really understand a subject it can be put in terms that a 15-year-old boy can comprehend."

Sociology and psychology offer further illustration of specialized terminology, but we cannot tarry with them for there are one or two other points to be made. The Chancellor from Kansas, Dr. Clarke Wescoe, expresses the opinion that in our day the town and gown syndrome is almost entirely limited to medicine. Conceding an historic town-gown conflict, including both faculty and students, which goes back to the founding of universities in the 13th century, the good doctor feels that such conflict of interests has in our day practically disappeared, except in medicine. If the Chancellor is correct it rather knocks the bottom from the general concept behind this column. Agreeing with the doctor that the town continues to tolerate the gown because it is a source of economic support, some sort of difference is still observable and is more observable in towns of small population as is the case in the Hanover-Norwich complex.

Whether syndrome applies to this particular inflammation may be open to question, particularly since the definition quoted alone makes syndrome apply to causes of an "abnormality." There doesn't seem to be anything abnormal about the difference between town and gown in Hanover. Very rarely is it at all a tense or troublesome difference but it is a difference which is there - like sex. From the townsman's point of view some earn their living the easy way - reading books and teaching classes - and others keep the wolf from the door in a more difficult fashion - selling goods or services to a demanding public. The gown is viewed as impractical and idealistic - even Democratic with a capital D - while the town knows the value of a dollar'and favors a more conservative economic policy. And there is always just enough truth to this charge to give Harry Tanzi or John Piane or Dick Putnam plenty to talk about. And the tendency of the younger gown to fall into the new terminology, in public gatherings for example, sometimes makes communication difficult. Even the Chancellor uses such terms as "genetically recessive" and "etiologic factors" and "exacerbations and remissions" - all in discussing the town and gown syndrome.

Fortunately, when one wants bananas there is no need to beat around the bush with words, and if it is flowers or a new rug or a cup of coffee the same applies. So town-gown relations stay on a relatively pleasant basis, but as Harry Tanzi himself says, "If some of these profs, in promulgating their esoteric cogitations, would beware of pompous prolixity, ponderous verbal proliferations, and psittaceous vacuity, this town-gown syndrome you're talking about could be brought to more accurate diagnosis." Perhaps what we need, says Harry, is another ad hoc committee!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA BLUE-CHIP ASSET FOR 50 YEARS

April 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21, CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureOldest Living Graduate, Will Be 100 This Month

April 1964 By Dr. Edwin H. Allen '85 -

Feature

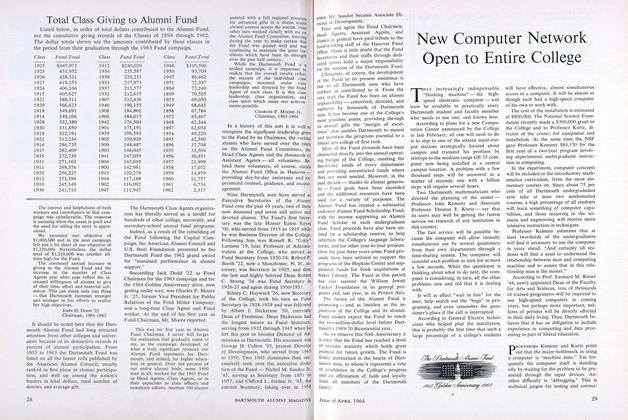

FeatureNew Computer Network Open to Entire College

April 1964 -

Feature

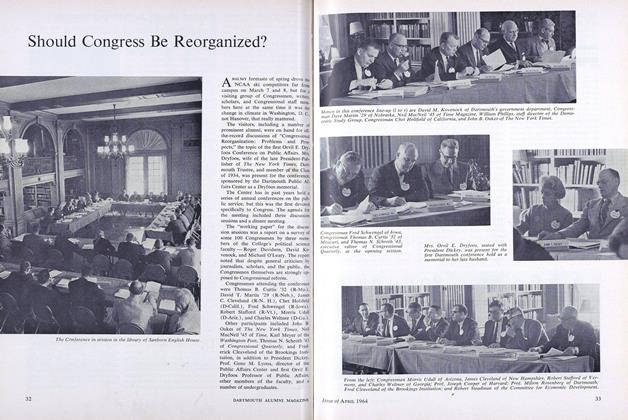

FeatureShould Congress Be Reorganized?

April 1964 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

April 1964 By KENNETH W. WEEKS, HERMAN J. TREFETHEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

April 1964 By CHAUNCEY N. ALLEN, PHILLIPS M. VAN HUYCK

ALLEN R. FOLEY '20

-

Books

BooksA HISTORY OF LUMBERING IN MAINE, 1820-1861.

December 1935 By Allen R. Foley '20 -

Books

BooksFRONTIER OHIO

May 1936 By Allen R. Foley '20 -

Books

BooksTHAT FAR PARADISE.

May 1960 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

ArticleDRESDEN SCHOOL DISTRICT

JANUARY 1964 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

ArticleONCE AGAIN ACROSS THE RIVER

FEBRUARY 1965 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Books

BooksVirgin Dip

June 1976 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

March 1944 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah for —

MARCH 1969 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Award: Allen Vincent Collins ’53

Winter 1993 -

Article

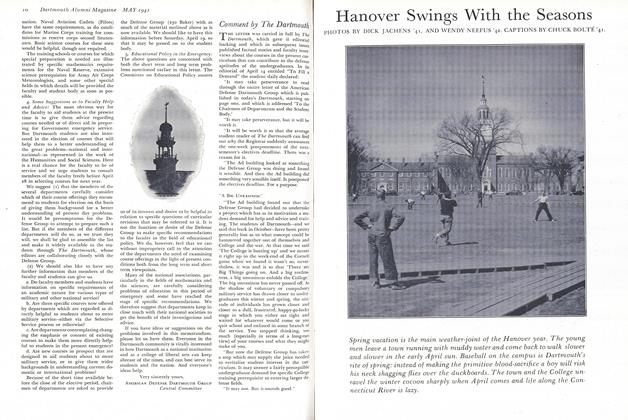

ArticleHanover Swings With the Seasons

May 1941 By CHUCK BOLTE '41 -

Article

ArticleFreshman Orientation Studied

January 1952 By Conrad S. Carstens '52 -

Article

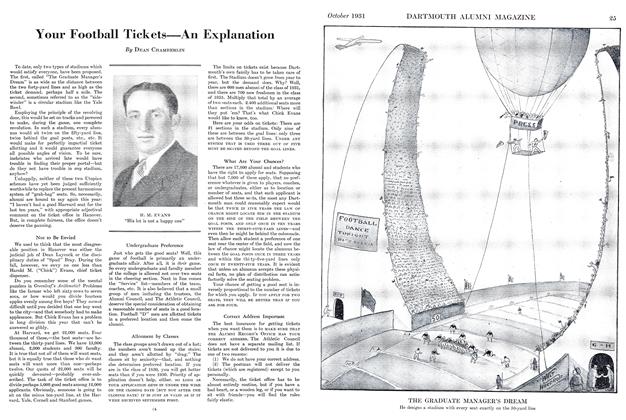

ArticleYour Football Tickets—An Explanation

OCTOBER 1931 By Dean Chamberlin