We have been walking past Wilson Hall (the old library: the new museum) at least six times a day for the past semester. Last week our reportorial curiosity finally drew us in. The dark, cramped, depressing old dump where we spent as little time as possible fulfilling course reading requirements during our freshman and sophomore years, had become a remodeled, newly-painted, airily skylighted museum, well-equipped and surprisingly well-filled for an un-metropolitan college.

It is a museum not without local color. The piece de resistance, which one encounters immediately upon entering, is the historic Hanover stage-coach. This glorified buggy has hauled its generations of Dartmouth men up from the Norwich station. It fills the entrance salon of the new Dartmouth College Museum with a certain superb majesty. It is almost impertinently healthy, having been a little too well "restored" by an over-zealous painter who, with scant respect for its almost centenarian years, has dressed it up with copious yellow paint and red curlycues, like a wagon in a country hardware store. But it still inspires respect.

We had passed on to the inspection of the inside of a cast of a pre-historic turtle's shell, large enough for a comfortable week-end camping tent, when the museum attendant appeared and started telling us that the animal skins on the walls were another Sanborn gift, and that a pair of tusks which looked as long as the Senior Fence were casts from the tusks of a pre-historic animal in the British museum.

The attendant, with his apparent genuine interest, began to become interesting by his contrast with the usual museum perambulating phonograph. We began to have suspicion of an artist's soul when, as we were inspecting some cases of sea shells, he set out to describe the exquisite tints which the late afternoon sun brought out in the shells. A brief inspection recorded reflective blue eyes, New England features of the kind traditionally described as "rugged", and sound middle age. The keynote of his costume was comfort. A celluloid collar was the only concession to Art.

And a brief conversation revealed that lie had given up a life's career as a teamster to enter the museum last June, not as an apostate from his chosen calling, but as a refugee from the conditions of the motor age. And when we got back to the stage-coach, and a consideration of its construction and the difficulties of driving it, it was plain that the art of the master teamster was still the art that filled the warmest chambers of his soul.

Proceeding through the other exhibits, we found a rainbow display of butterflies, innumerable bugs and beetles, and an interesting alcove of mounted birds, from eagles to humming-birds. The Sanborn collection of fresh-water fish is perhaps the largest in the world.

In the ethnology room is the mummy of an Ethiopian princess of the 24th dynasty (700 B. C.). Here also are the gypsum bas-reliefs from the palace of Assur-Nasir-Apal (himself), that cheery old Assyrian monarch. He ruled 200 years before his successor, Assur-Something-Else, developed Ninevah, 25 miles away. There are also numerous artifacts of ancient times and of far places—costumes, weapons, utensils, art from Japan, India, Fifi, the Pacific Islands. And there is an American Indian room with exhibits of the same nature. Not to mention minerological and geological exhibits, and numerous odds and ends.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1909

March 1930 By Robert J. Holmes -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

March 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

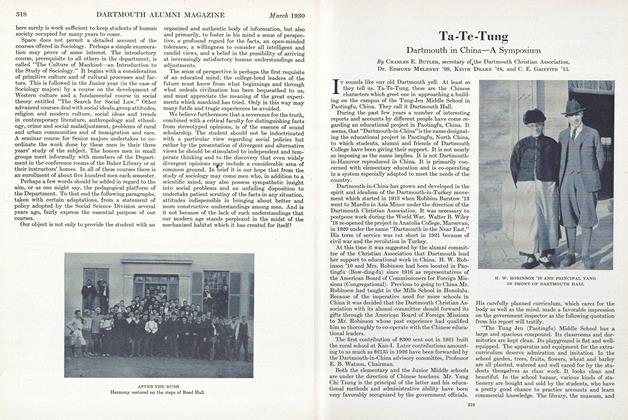

ArticleTa-Te-Tung

March 1930 By Charles E. Butler -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

March 1930 -

Sports

SportsFootball at Dartmouth Since the War

March 1930 By James P. Richardson -

Article

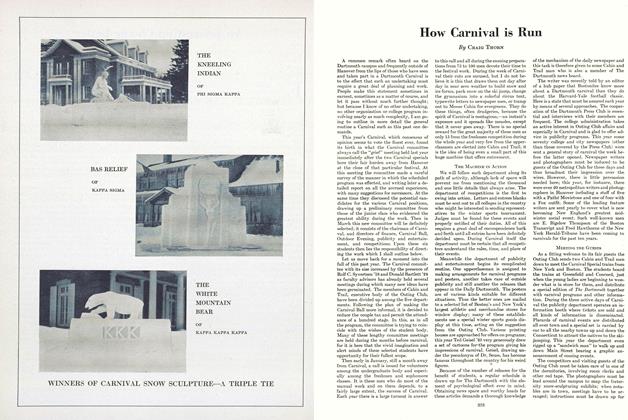

ArticleHow Carnival is Run

March 1930 By Craig Thorn

Albert I. Dickerson

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleWandering Thespians

May 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleThe Round Table

June 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

DECEMBER 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

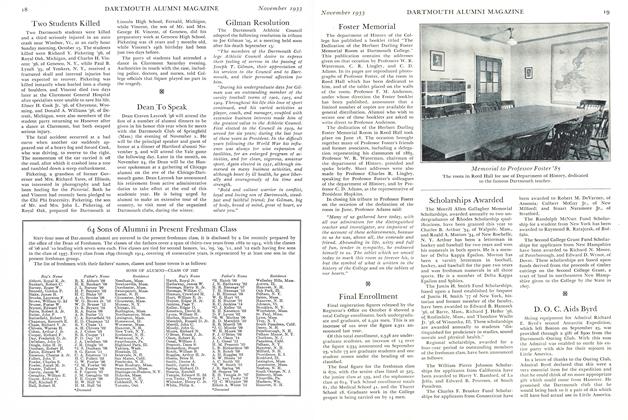

Class NotesClass of 1930

November 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

January 1939 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON

Article

-

Article

ArticleFinal Enrollment

November 1933 -

Article

ArticleGood Soldier

April 1941 -

Article

ArticleClass of 1960

Mar/Apr 2009 By Bonnie Barber -

Article

ArticleA Wall Hoo Wah!

February 1951 By C. E. W. -

Article

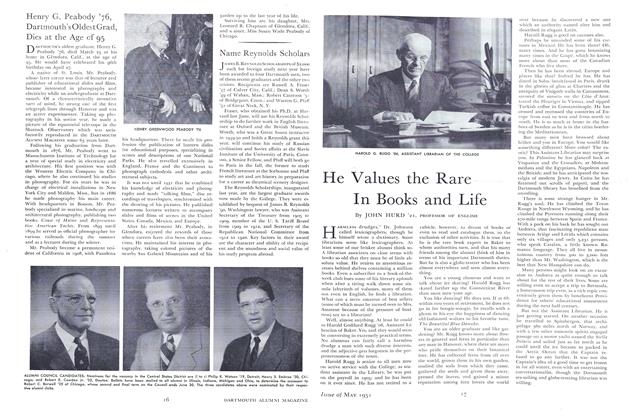

ArticleHe Values the Rare In Books and Life

May 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleSteel and Crinoline

May 1979 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38