Article One, 1919-1922

The story of "athletics at Dartmouth" has been broughtto 1923 in the boohs known to all Dartmouth men, chieflythose of Benezet and Pender. Professor Richardson, amember of the athletic council in the "troublesome times"of the early Post-war period, here carries on the storyof the football teams and in his first article covers theclosing years of the Spears regime and the trial period ofthe advisory-board experiment with Cannell as fielddirector.

NOW that the season has arrived when football in these latitudes can be played only in prospect or retrospect, it is possible that the Dartmouth "'hot-stove league" will not object to a little additional fuel. i

The perfect "fan" present at every Dartmouth football game since the war, would have seen 94 contests; 71 times he would have been able to exult in a Dartmouth victory; 20 defeats would have saddened him; and three ties would have left him unsatisfied. These ties were the memorable 7-7 game against a great Colgate eleven in 1919, when "Swede" Youngstrom averted defeat by one of his kick-blocking specialties, and the kick after touch-down hit an upright and bounded the right way; an unsatisfactory 14-14 game with Pennsylvania in 1921; and an even more unsatisfactory 14-14 result in the Yale Bowl in 1924—the start of the still present Yale "hoodoo."

Of course a great many of the victories came against the smaller colleges, and it is to be noted that Dartmouth has been upset during this period only once by a college supposedly in a lower football class; this was that extraordinary game in 1922, against a remarkable Vermont team, which won a 6-3 verdict, all the scoring being by field goals. One who is really interested to know whether Dartmouth teams have had their fair measure of success must look for the record against our major and constant rivals. These, taken in the order of frequency of games played, are Cornell, Brown, Harvard, and Yale.

Against them, the 1919-1929 record is as follows: Opponent Games Played Won Tied Lost Cornell 11 7 4 Brown 10 7 3 Harvard 8 5 3 Yale 5 0 1 4 Totals 34 19 1 14

So it will be seen that in an eleven-year stretch Dartmouth has won close to sixty per cent of her contests against four doughty rivals. Why should even the most rabid victory-hound ask or expect anything better? It must be admitted, though, that the Yale figures are all wrong, and that "something ought to be done about it."

During this period there have been three head coaches: Spears 1919-20, Cannell 1921-22, Hawley, 1923-28, and Cannell again in 1929.

In the same time there have been three really great Dartmouth teams. Of course the unbeaten, so-called "championship" team of 1925 comes first to the mind, and that was a great outfit; but the unbeaten team of 1924, tied only by Yale, was about as good; and the team of 1919 which lost only to Brown and that by a single point, shared with Colgate the top -ranking in the East, and would have given either of the others a tremendous battle. The "inside" story of the loss of that game to Brown (the score was 7-6), may not be known to everyone. Dartmouth was leading 6-0. With only a few minutes to play, substitutes went into the game. A punt was called; one substitute forgot his primary duty, and rushed down the field; the Brown man came through the gap, blocked the punt squarely, caught it as it rebounded from his chest, and made an easy touchdown.

The record of the fine team of 1927 was marred only by an off-day against Yale, resulting in a 19-0 defeat; and the failure of the 1929 team to make as good a record as any was probably due solely to the unfortu- nate injury to Marsters, and is fresh in the mind of everyone.

POST-WAR SCHEDULES

In the post-war seasons, college football schedules were completely rearranged. Relations were built up between Cornell and Dartmouth which still continue as very pleasant and very vital. Columbia, Pennsylvania, Penn. State, Syracuse, and Colgate furnished much of the interest to the schedules of this period, but as time went on these colleges entered into other schedule grouping. The exception was Columbia which returned to the Dartmouth schedule after a few years of absence, and the Columbia game in New York is now taking on increased interest to both Dartmouth and Columbia alumni and students. Home and home arrangements with colleges have always been rather difficult because of Hanover's isolated position which guarantees crowds of by no means the size that can be guaranteed at Philadelphia, New York or Syracuse.

But the early post-war schedules were "roving." There was no definite assurance of home and home arrangements with any team from one year to another. In those days a schedule for a season was not made up until the conclusion of the one next preceding; this was the universal practice and the conduct of intercollegiate relations resembled the pre-war diplomacy of Europe. At least so far as Dartmouth is concerned, a great change has taken place, and with the development of more or less steady schedule with opponents from colleges of student bodies of about the same size as Dartmouth has come a growth in the broadest sense of athletic standards. While all the credit for this does not belong to any one man, it is yet true that the sagacity, patience and foresight of Joseph T. Gilman, member of the Council from 1920 to 1925, stand out most conspicuously in this movement. It is doubtful if his contributions to the college have ever been widely enough known or properly appreciated.

The chief criticism of the teams coached by Spears (1917, 1919, 1920) was that they lacked the "scoringpunch." Though numbering many powerful and brilliant players such as Youngstrom, Robertson, Shelburne, Jordan, Cannell, Sonnenberg, Neidlinger and others, a great deal of their efforts seemed to be wasted. A glance at the scores of those three years will show that in only one game against a major opponent did Dartmouth "run up a score." This was against Pennsylvania in 1920, when "Chick" Burke had the most brilliant day of his career, and Sonnenberg showed the Philadelphians something about punting. The score of that game was 44-7.

Spears was a great defensive coach, however. The largest number of points made against Dartmouth in 1919-20 was 19 by Pennsylvania in 1919, in the game won by Dartmouth at the Polo Grounds, 20-19.

Spears was a drill-master. He was not one of those ■coaches who could instil the element of fun into practice. He took every game with tremendous seriousness, and for about forty-eight hours in advance of each he was like a caged animal. The weather in Seattle, after the arrival of the team there on their Washington stadiumdedicating trip in 1920, was, as it sometimes is in that city, rainy and windy. The new field had no turf on it, only a kind of mealy sand, and on the day before the game was about three inches under water. On the evening preceding the game the coach, whose temperature had been rising steadily as the continent was crossed, inquired mildly of the writer if he proposed to hire diving suits and play at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. Curiously enough, it did not rain on the day of the game, but another and more serious explosion was narrowly averted when during the first half, with Dartmouth on the offensive for the first time, after the Westerners had scored a touchdown, Dartmouth was penalized something like sixty yards in four or five successive plays. The Dartmouth team, following Eastern interpretation of the rules, had been using their hands in such a way as to offend the Western officials. However, trouble was averted and the Dartmouth team began to show its unquestioned superiority, under any rules. The final score was 27-7, and after that, no more cherubic individual than the Doctor could be imagined.

INTERSECTIONAL GAMES

Mention of this game brings up the whole subject of intersectional and postseason games. During this period Dartmouth has played four intersectional games, as follows: 1920 Seattle—Dartmouth 27, Washington 7 1921 Atlanta—Dartmouth 7, Georgia 0 1925 Chicago—Dartmouth 33, Chicago 7 1928 Chicago—Northwestern 27, Dartmouth 6

From personal observation of three of these four trips, the writer is prepared to subscribe himself as a thorough believer in an occasional game of this sort; the more intersectional the better. Such a trip as that to Seattle can be made a positive benefit to everybody concerned, provided it is carefully planned beforehand and properly managed, as that one was. Not one of the undergraduates on the trip had ever been to the Pacific coast; nor the next year, had any of them ever been in the heart of the South. If such games and trips are properly scheduled and arranged, they do not involve nearly so much loss of class time as might be thought, and it is perfectly possible to arrange successfully for "study hours" en route. One of the interesting and valuable by-products of the Seattle trip was the formation of the "Green Key," a society copied from "The Knights of the Hook," which exerted itself with great success for the entertainment of the Dartmouth visitors at the University of Washington. That the alumni in districts far away like to have the flavor of the college brought to them occasionally goes without saying. Such journeys should never be undertaken when the chief inducement is financial. It is to be hoped that Dartmouth will never be tempted to indulge in any Tournament of Roses hippodroming.

The game with the University of Georgia at Atlanta in 1921 came too soon after the long trip to Seattle to be theoretically justifiable. It was arranged partly to piece out a rather short schedule, and partly because the invitation from our Southern friends came so warmly that it could hardly be declined without discourtesy.

In the event, this game, won by Dartmouth 7-0, proved to be the saving grace of an otherwise rather disastrous season; and was successful from every standpoint. If the writer were asked to name the most spectacular play he ever saw in a football game it would unquestionably be the fifty-yard forward pass from Robertson to Lynch at the end of the first half on which Lynch made the only score of the game. It was "the perfect play," and for years it was talked about in the South. After the game, Burleigh, the timekeeper, said that the time of the first half expired while the ball was in the air.

The success of the Dartmouth teams in 1919 and 1920 under the coaching of Spears led to his receiving other salary offers beyond anything that the Athletic Council could meet, and so Dartmouth and Coach Spears parted company, with sincere regret, at least so far as the Dartmouth athletic authorities were concerned. His later successes at West Virginia and Minnesota have been hailed with satisfaction by Dartmouth men everywhere.

NEW CONDITIONS IN FOOTBALL

Spears warmly recommended Cannell who had been his assistant in 1920, as his successor. And with Cannell began the new era in Dartmouth football. The young coach, just out of college, faced in 1921 the remaking of a whole system. Some half-dozen men had returned to college who had been members of the varsity squad of the year before. The rules against the shift-plays which had added much to the color of the game in the late 'teens were just being formulated and it was a much changed game that football lovers saw that fall. Cannell whipped into shape a team of mostly green men, not "Big" green men either, for there was always the question of "who was going to play which position" both in that season and the following season. Robertson, captain for the second year, was suffering from injuries which kept him from rounding into his best form.

But the team of 1921, and the team of 1922 a year later, both played with incredible spirit. In 1921 it bowled over Tennessee and Columbia and Georgia, fought to a tie with Pennsylvania, and lost to a good Syracuse team, 7-14. The season would have seemed a success, and a success much greater than critics had ever given it credit for, had the team not lined up against Cornell, which in that season and the next possessed one of the strongest teams in the history of American football. Those 1921 and 1922 Cornell teams (and with- out forgetting the 1923 team either), simply swept over Dartmouth as they did all their opponents. The backfield combination of Kaw, Pfann, Ramsey and Cassidy, was functioning for Cornell and those four would contest with Notre Dame's "Four Horsemen" the right to an all-time Ail-American backfield unit title.

The next year an advisory board took charge of the football situation at Hanover consisting of Cannell, Jess Hawley, Clark Tobin, and Larry Bankart. In the Harvard game of that year Dartmouth put up one of the finest and most spectacular games in its football history. Halsey Mills, seemingly recruited out of the Dartmouth Players for the football field, performed antics in the Stadium that made the spectators wonder what would have happened had he come out for football at an earlier period. His running back of kicks, and his dodging in and out, kept the Dartmouth stands enthusiastic through much of the game. The score, Harvard 6-Dartmouth 3, was not a decisive one, until the fourth quarter when a Harvard man intercepted a forward pass and ran for a touchdown, making the final score Harvard 12-Dartmouth 3. Vermont came to Hanover that year with one of the strongest teams in her history and won from Dartmouth in a well-played game, all the scoring coming from field goals. The final score was Vermont 6-Dartmouth 3, and the time was up while Dartmouth was making a terrific drive on the Vermont goal.

A PERFECT GET-AWAY MARRED BY A FUMBLE

CORNELL AT POLO GROUNDS, 1920

"JESS" HAWLET

DARTMOUTH-PENN STATE, 1919

PROFESSOR

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1909

March 1930 By Robert J. Holmes -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

March 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

ArticleTa-Te-Tung

March 1930 By Charles E. Butler -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

March 1930 -

Article

ArticleHow Carnival is Run

March 1930 By Craig Thorn -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Intellectual Life

March 1930 By Erville Bartlett Woods

James P. Richardson

-

Books

BooksTrade Associations

August 1921 By James P. Richardson -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JUNE, 1928 By James P. Richardson -

Article

ArticleCampus Competitions End

JUNE, 1928 By James P. Richardson -

Article

Article"Unknowns" Win Prizes

JUNE, 1928 By James P. Richardson -

Article

Article63 Students Have Cars

JUNE, 1928 By James P. Richardson -

Books

BooksEDWARD COKE, ORACLE OF THE LAW.

FEBRUARY 1930 By James P. Richardson

Sports

-

Sports

SportsMICHAEL WINS TITLE IN FANCY DIVING EVENT

MAY 1927 -

Sports

SportsGoals

November 1980 -

Sports

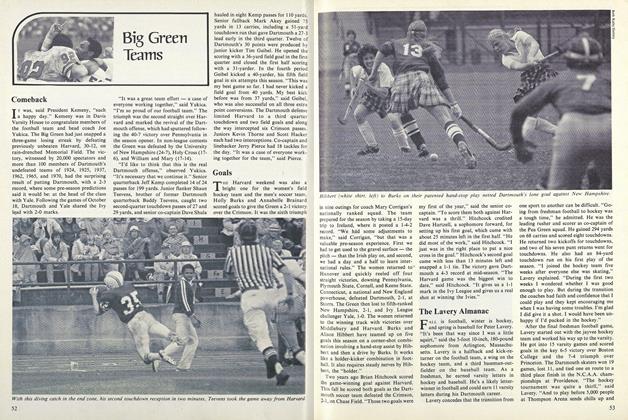

SportsWomen Hoopsters Share Title

MAY • 1988 By Charles Young '88 -

Sports

SportsOH, SWEET VICTORY!

December 1988 By Chuck Young '88 -

Sports

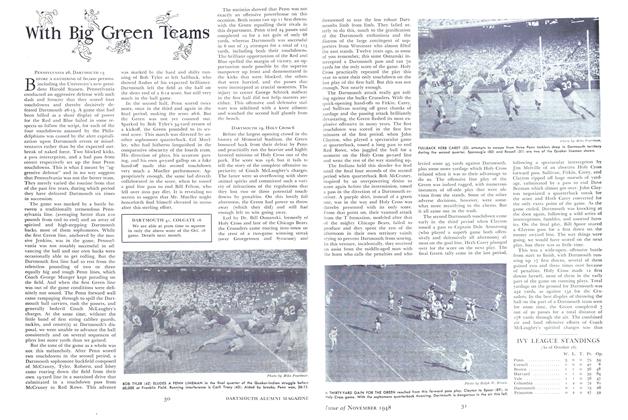

SportsDARTMOUTH 19, HOLY CROSS 6

November 1948 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsMISCELLANY

November 1948 By Francis E. Merrill '26