By Bruce Winton Knight, and Nelson Lee Smith. Two volumes. New York, The Ronald Press Company, 1929. Pp. x, 1019.

"Eccy" 1 and 2, which are elected by most Dartmouth men during sophomore year, endeavor to carry out the primary purpose of a liberal college, which is to prepare men for citizenship no less than for personal success. This book, written by two members of the staff in charge of these courses, and now being used as a text in them, manifests this purpose. It elucidates the principles of economics in the effort to enable men not merely to succeed in business, but also to appreciate their social responsibilities. Perhaps the most characteristic feature of the book is the striking way in which it gives economic processes their setting in life as a whole. The science of economics is seen in its relationships with kindred subjects, especially ethics, political science, social institutions, psychology, and the philosophy of values.

Economics is defined as "the study of social efficiency in the production, consumption and distribution of wealth." Economics is subdivided into economic science and economic philosophy. The former is concerned with the observation of events with a view to their prediction and control, and employs the ordinary scientific methods of induction and deduction. The latter makes a valuation of the results of the economic processes. Economic science and economic philosophy, though never confused by the authors, are not discussed in isolation; in many chapters they are brought together, and their mutual implications are disclosed.

The present reviewer, being a philosopher and not an economist by profession, will for the most part have to confine himself to a report on the economic philosophy of the book. However, he might say, that, so far as he is competent to judge, the exposition of economic science is remarkably lucid and well reasoned. Although he has always regarded graphs with horror, he can follow those in this book without difficulty; he even finds them illuminating and interesting. The treatment of price and distribution appears particularly good; obviously these topics have received special thought and care. Another conspicuous feature is the interpretation of efficiency in production. This latter is determined by the volume of resources available for use; by the apportionment of these resources among possible employments; and by technological efficiency within each employment. An attempt is accordingly made to put problems of economic science in relation to these determinants of productive efficiency, as well as to consider their effects upon distribution. The exercises at the ends of the chapters are concrete and stimulating; probably most of them were tried out with classes while the book was in preparation.

In the second chapter, the place of our present economic order is indicated in a classification of those forms of economic organization that have at times been thought to be speculatively possible. (The authors do not assert that all of them Jre really possible, and could be made to work.) An economic organization might assume the form of authority, either that of a minority group (autocracy) or of the people as a whole (democracy); the latter might govern by majority rule in political matters only (as in a New England town meeting), or in both political matters and in functions of production (state socialism), or in all the functions of production, distribution and consumption (communism). On the contrary, economic organization might be free from the authoritarian control of a central governing body (freedom); on this supposition there might be no socially organized control at all (anarchism), or little or no central control of diverse economic groups (syndicalism). Under the heading of Compromise (between the extremes of Authority and Freedom) the possibilities listed are guild socialism and our present economic order, for which latter the authors prefer the terms "competition" and "the competitive process" to "capitalism" or "individualism." Competition recognizes the rights of property, contract, and free competition, and government intervenes in the economic order only when it is impracticable to rely upon individual initiative for guidance of production, consumption, and distribution, as in the case of monopoly. In estimating the desirability of the competitive system in comparison with the various imagined alternatives, it is necessary to be clear what we are comparing. Under no practical alternative could certain economic laws and conditions become different: there could be no escape from the laws of "diminishing unit desire" and "diminishing returns," nor from the machine process, nor from specialization, nor from some medium of exchange in terms of which social costs might be reckoned.

It is also necessary to understand what we mean by a valuation of the present system in comparison with possible alternatives. Here the philosophy of values comes in. Indeed, the relation of economics to the philosophy of values and to ethics is becoming most important in view of the increasing possibility of measuring values on a pecuniary basis. To do this sharpens and clarifies values, without in the least debasing them, or obscuring their significance in the attainment of life on its higher levels. In their philosophy of values our authors are instrumentalists, influenced chiefly by John Dewey and H. W. Stuart, and in a more general way by William James and other pragmatists. Any process of valuation implies a situation containing one or more persons, objects (not necessarily physical), and purposes (of the persons with reference to the objects). Men relate objects to the discharge of purposes. In doing this, they may make comparison of ends, or of means, or of both. If ends are compared qualitatively ethical judgments are called for; but once choice of ends has been made with reference to available means, the situation demands quantitative or economic judgments. A process of valuation is likely to begin with ethical judgments and to end with economic judgments.

Values, both ethical and economic, are constantly changing with individual preferences. A type of consumption may vary in its physiological, cultural and prestige values. Nor are all values restricted to consumption. Production, too, is of positive value; on this our authors insist; work is, or ought to be, of intrinsic value for its own sake, whether viewed hedonistically as a form of pleasure, or eudaemonistically as a mode of self-realization. In general, the ethical position of our authors seems to be that of self-realizationism or eudaemonism; however, little or nothing that they say would not be equally acceptable to a utilitarian.

Since values are constantly changing, and no absolute frame or scale of values can be established, value standards at the present, or at any other given time, must be based upon the agreement of those most competent to judge. Ethical values are intuitively discerned and are qualitative, being either creative or appreciative; while economic values are rational, in the sense of a quantitative comparison of means after ends have already been determined.

With the methods of valuation thus established, the cases for and against competition (our present economic order) are considered. The case against competition is in many ways a serious one, especially from the standpoint of consumption. The present inequalities in distribution tend to reduce the total amount of satisfaction in the world (i.e., the reviewer supposes, they tend to make people less good and less happy). Inequalities are out of all proportion to the distribution of merit and natural ability.

On the other hand, the competitive system has many substantial advantages, especially on the side of production. Its tendency is to fix prices at the figure expressing both marginal demand and marginal cost. It thus causes the goods to be produced that society wants. It stimulates persons to produce according to their ability (except in the case of inheritors of wealth, on whose ethical and economic justification the authors are hesitant). It favors increase in the volume of capital, which is a social good.

Oil the whole our authors are inclined to counsel us to adhere to our present economic system, provided we keep mindful of its faults and endeavor to correct them whenever possible. We should particularly be on our guard against monopoly, and wherever it tends to arise, either restore free competition or assume governmental control. The authors do not consider that attempts to regulate the railways have thus far proved satisfactory, and they are inclined to ask whether governmental ownership and operation may not become desirable. In the chapter on Population, in the course of a careful estimate of the elements of truth in Malthusianism, they courageously point out the economic advantages of birth control. They are firm believers in the natural equality of mankind, and think that, so far as possible, social and economic arrangements ought to give every one the opportunity to live in accordance with his ability, efforts, and achievements.

The reviewer finds himself almost entirely in agreement with the authors, and has little to say by way of criticism. The evils of advertising are justly and emphatically pointed out in the book; some but perhaps not adequate recognition is given to the necessity of advertising in a competitive system; more attention might have been given to the considerable reforms that have been effected in recent years, largely on the initiative of advertisers themselves. The position of the anthropological school which affirms that there are no differences in native ability between races and few between individuals is almost uncritically accepted; the opposite position, for which there is some evidence {e.g. intelligence tests) has not enough been taken into account. However, these criticisms refer to passages that occupy only a slight portion of the book, and it was obviously impossible to discuss all sides of every problem in an introductory text.

The book is carefully written, is clear, logical, interesting, up-to-date, and in short, everything that a text ought to be. A smaller format and more compact volumes, easier to slip into brief cases and overcoat pockets, would in some ways have been preferable; however, that would have meant thinner paper and smaller type. The volumes are excellently made, and the typography is almost perfect. WILLIAM KELLEY WRIGHT

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

May 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

ArticleSome Memorable Teachers

May 1930 By Professor E. J. Bartlett -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

May 1930 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1909

May 1930 By Robert J. Holmes -

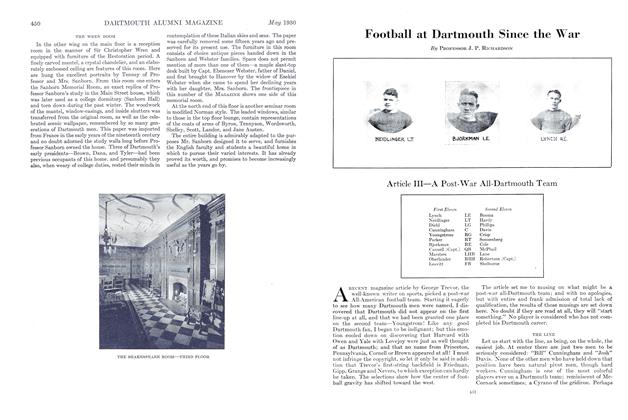

Sports

SportsFootball at Dartmouth Since the War

May 1930 By Professor J. P. Richardson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1908

May 1930 By Secretary, Arthur B. Rotch

Books

-

Books

BooksIDENTIFICATION OF FIREARMS FROM AMMUNITION FIRED THEREIN—WITH AN ANALYSIS OF LEGAL AUTHORITIES

March 1935 By C. J. Campbell '17 -

Books

BooksA SHORT FRENCH GRAMMAR FOR COLLEGE STUDENTS

May 1940 By Charles R. Barley -

Books

BooksSWITZERLAND ON FIFTY DOLLARS

May 1934 By Frederic P. Lord -

Books

BooksTHE RECOVERY OF CULTURE

February 1949 By Herbert F. West '22. -

Books

BooksTRAIT-NAMES: A PSYCHO-LEXICAL STUDY

May 1936 By Irving E. Bender -

Books

BooksMASSACHUSETTS PROCEDURAL FORMS, ANNOTATED,

October 1949 By W. Langdon Powers '34