ONLY children carry bouquets to teacher. And they cease from this beautiful custom when they are no longer "dear little things" and when teacher has stopped kissing the bright morning faces. From the time when the little ones arrive at years of criticism eight or ten onward—it is the teacher's fate to be regarded as a necessary evil during business hours, and, now that the period of comic valentines has passed, his good fortune to be forgotten out of school. Teachers expect too much and they should be discouraged. Teachers are professional critics and invite retaliation. My teachers are all beyond bouquets, discouragement or retaliation; but they were a remarkable group, or rather, series, and I can now write of them mixing sketchily the notions of a child with the judgment of later years.

First of the teachers, an object of horror and execration which I am now sure was unjust, was a young person who in modern times would be called a kindergartner. She kept a little dame school where instead of making mats of colored straws for mamma we learned to sing "Lightly row." "Lightly row; lightly row; o'er the" and it was years before I knew whether it was "o'er the 'glassy' ways" or "o'er the 'grassy' waves we row." I finished with her before I was seven, but she deeply impressed and I think injured my youthful sympathies by her penal system; and that is why I remember and mention her. Whenever one of those little tots was over-wicked this monster caused the pink infantile tongue to be stuck out, tied a string around it and drew the string tight in the sight of all. What torture! How awful! I was careful to be good enough not to be caught in any crime; but the impression, the shock, has remained with me these seventy years. Of course I am sure now that this discipline was only what the moderns call a gesture and never hurt any one. But it was real enough at the time.

One of those little buds whom I never saw again grew to be a charming young woman, married, died; and her bereaved husband gave Dartmouth one of its most beautiful buildings. The threads of life get strangely intertwined; but this benefaction is unrelated to any lingual misdemeanor.

MRS. ELLA FLAGG YOUNG

Five years and a thousand miles away found me in a great public school in a room suitable to my age, and dominated by another miss, of nineteen years. Of course this information relative to age is not guaranteed but is based on information which I consider reliable. As I remember her she was dark, sallow and always wore a black dress and a severe expression. She had a habit of puckering her lips in an osculatory manner; but with her it meant displeasure and conveyed a threat of discipline. She did not win my young affections, but I suppose that is to my discredit for some of the girls in the higher rooms of the school found her very companionable. I think that she was consciously maintaining the dignity of a young teacher not yet assured of her position. She never had to call upon the principal to keep her young insurgents in order; she attended to them herself. Her name was N. Ella Flagg. Was it Nancy or Nellie or Norah? I never knew. Years later I was again in her room, but a different one; for she went rapidly to the top. From it I went to the high school, and that year one of her pupils received the highest marks of any in the city, thus bringing distinction to the young teacher. This teacher was better known as Mrs. Ella Flagg Young, for a time superintendent of Chicago schools, professor in the University of Chicago and president of the National Teachers Association.

REV. W. A. AND MRS. NICHOLS

Bad air, exciting examinations and attempts to grow caused me to droop and my parents transferred me for a time to a, home school for boys at Cleaverille in the country not far from the present site of the University of Chicago. It was kept by Rev. and Mrs. W. A. Nichols, good old souls, the very best, but perhaps not so old as I thought. Small boys were there of names well-known in the history of Chicago Armour, Bradley, Caton, Flint, Singer, Thompson, Williams, and two sons of Mother Bickerdyke as famous for good works in the Civil War as was Florence Nightingale in the Crimea. She came to see her sons, Hiram and James, and told us sad stories of the suffering soldiers in the poorly-equipped hospitals. Imagine army hospitals in which there was no antiseptic treatment and in which the older surgeons had learned their trade without anesthetics! Mother Bickerdyke was no bashful violet but was built to receive attention when she demanded it. I am sure that being good was a strong point with the Rev. Nichols and wife; and I do not make that claim because we had to read the Bible in regular course not skipping the genealogies and to say a verse every morning at breakfast, but because much more important to us then—we were abundantly fed, well and kindly cared for and compelled to give large time to those healthy running games which were full of zest for boys, and girls too, before ever baseball, tennis or golf were known to small people. Neighbors' children joined in our sports and it was then that I learned that girls could run like deer if only they had a chance. It was a real home school, and it did me no harm that I learned musa,musae and all that before I knew there was such a thing as English grammar. The Rev. Nichols lived many years after his boys had grown up and he kept track of them; so I think that in my time he was not so very old after all. He had one famous sermon from the text "Go, run, speak to that young man." "That young man" was speeding down the macadamized way, and perhaps your speech would start him back up the grade. Do you see? Another of the good dominie's texts, "His driving is as the driving of Jehu the son of Nimshi," might well be given to the theolog of today as an exercise in sermon building.

This connecting link between teachers for here is no autobiography came back invigorated from the country, and in due season moved on to the high school where as usual the incoming multitude were distributed through several rooms. Happily I was assigned to the care of a quiet self-possessed young man in whose room, to the best of my recollection, the question of order or discipline never arose to any importance. I can remember smooth uneventful school routine.

One memorable occasion there was, with a sequel. The annoying custom of speaking pieces was still with us "When my turn came around the ever pressing question arose, "What shall I speak?" My father to whom I applied in desperation suggested Hamlets speech to the players, "Speak the speech I pray you as I pronounced it to you, trippingly on the tongue; but if you mouth it as many of your players do, I had as lief the town crier spoke my lines." Now just before my turn to deliver, an extremely dramatic youth, a howler in fact, spouted "The Polish Boy." To the best of my understanding a young man somewhere in Poland was going to be shot for political reasons and his mother interceded for him in vain. This truly sad affair caused the speaker to shriek, writhe, cry to high heaven and shed tears. Perhaps it was not an accident that 1 followed, self-conscious and discouraged after such magniloquence, and recited my little piece without much animation. My readers of course know what I said, "Nor do not saw the air with your hand thus; but use all gently" . . . "Oh, it offends me to the soul to see a robustious periwigpated fellow tear a passion to tatters to very rags to split the ears of the groundlings "Oh! there be players that I have seen play and heard others praise and that highly that have so strutted and bellowed that I have thought some of nature's journeymen had made men and not made them well they imitated humanity so abominably." I sat down sad and humble at the contrast between my own insufficiency and the stormy tragedy of my predecessor; and it did not help me to see my teacher trying to hide a smile. As the years went by I came to understand what fun Selim H. Peabody, later for twelve years president of the University of Illinois, must have had from the contrast pointed by Shakespeare's own words. More than twenty-five years after this I had occasion to write to him about an appointment for one of our graduates and learned from his reply that he remembered the incident with joy. Anyway my candidate got the position though I never knew whether it was because of my recommendation or merely because he was the best man for the place.

LAKE FOREST ACADEMY

At the time to which I refer, soon after the Civil War, Lake Forest Academy had acquired little reputation as a seat of learning; but my father discovered that it would put me into college a year earlier than the less concentrated curriculum of the Chicago high school. The suburb was raw enough compared with its later refinement. It was very presbyterian, but it was getting rich and the school, though young, was on its way. The day scholars whose homes were in the village were a fine set of lads, but the morale of the school was notably lowered by the presence, in the boarding group, of boys who could not be managed at home. "Watch and pray was the maxim for the teacher, and on that basis Jonesy was the boy. He was young, but he concealed that fact from some by growing straw-colored chin whiskers. He was a veteran of the War. He had been a disciple of Professor Hitchcock at Amherst and thoroughly believed in running parallel "the march of the muscle and the march of the mind." So he was leader and example in our daily gymnasium drill. To this we wore uniforms —white shirts and long blue trousers with a white stripe —and, arranged in order of height we presented a glorious spectacle especially on exhibition nights when the gymnasium, a perfect specimen of kennel architecture, was brilliantly lighted with several kerosene lamps and the

cream of Lake Forest society was gathered. This was more than sixty years ago, and in the time and under the circumstances it was sometimes necessary for a teacher to assert himself and put audacious small boys in their proper place. When it had to be done it was worth while to see Jonesy pick up the offender, invert him, wave him in the air two or three times and set him on his feet unhurt but impressed with the idea that it was not well to fool with buzz saws. And he had to teach that is he had to make us learn Latin and Mathematics. And he did. From one end of the Latin grammar to the other, through the rules and exceptions of prosody we had to learn every word by heart and recite them in class. I do not claim that this was the best way to teach Latin; but I am thankful that he made us do one thing that could not be done more thoroughly. Some of those lists of Latin words occasionally rise to haunt me now. And when it came to the text every word was the basis of all the questions he could find time for,—construction, derivation, synonyms, history, geography, myth. He would have delighted the heart of "Uncle Sam" Taylor of Andover. For the time he was a great teacher, and we liked him. After a brief term of service as principal of the academy he became professor in Otterbein University, Westerville, Ohio and important in the educational affairs of the state. He lived to a ripe old age, most beloved by the students I am told by the president of the university. You see beneath his strict attention to business he kept a poorly hidden sense of humor.

In the last term of 1866-7, a temporary teacher arrived at Lake Forest who was to become later the first missionary of the American Board to Japan. His name was Daniel Crosby Greene, Dartmouth, 1864. He was twenty-three years old and inexperienced, and the experience he got in the academy was not good for him. The boys worried him and he was too kind to them. He appealed to their better natures and their better natures were not working at that time. If he had taken lessons from friend Jones and shaken up a few he would have found cut what nice little gentlemen they could be. Just forty-three years later I had the honor of presenting him, a man of great distinction, for the degree of Doctor of Laws from his alma mater, and the pleasure in a visit at my house of cautiously talking over our former acquaintance. In conferring the degree his old friend, President Tucker, spoke of Greene's forty years of leadership in the movement to establish the Christian religion in Japan and his constructive statesmanship in cementing the bonds between Japan and other peoples.

CHARLES A. YOUNG THE ASTRONOMER

It is not strange that among the college teachers whom I remember with respect Charles A. Young is preeminent. He was a distinguished man, and happily I came to know him best. I had only the slight classroom relation to begin with, but years later when I was lecturing in New York he remembered me and invited me to the hospitality of his charming home in Princeton; and after his retirement from active work I was often at his house in Hanover for the evening of whist which he enjoyed so much. In the classroom he was a man of one idea—the business of the hour and everyone knew it. He was exempt from the small trials of a teacher, except mental insufficiency on the benches. Everyone liked and respected him, though we had the frank reservation, not invariable towards teachers, that his mental processes were too quick and keen for us. horseplay was unthought of. At a time much later, in that same room, every man would rise at a quiet signal, take off his coat, hang it over the back of the bench and gravely sit down; soon everyone would soberly rise, recover his garment and again be seated. Unimaginable in Charley Young's classes. No one wanted to make any disturbance; and if he had I think the lightning would have struck him. I remember one occasion when by the sheer power of his personality he stopped an impending fight between two classes in the Old Chapel and marched the aggressing class out of chapel by the wrong door. It took quite a man to do that.

Our irritated milliner said to her discontented customer, "You know you have your face to contend with." Professor Young had our slow intellects to contend with. Undoubtedly most of us would have learned more from a less brilliant man, but I am glad we did not have to. He would explain with a piece of chalk and the blackboard, and the conspicuous victim hated to ask whether his figures referred to the function of x, the digamma, or the Morse alphabet. Then the professor would say, "You see the point?" to which the only answer was "Yes sir." But he was not deceived. One day he said, "Well, you may explain it." While the unhappy lad was getting his breath the clock struck. Professor Young laughed and said, "We'll have that explanation tomorrow." But he had not remembered that tomorrow was a holiday.

In our junior year 1871 the applications of electricity were rather crude, and once in a while the Holz machine would "go back on him much to his distress. I remember that he said to the class that it was doubtful whether the electric current could ever be subdivided so that it would be available for house lighting. Even then he was using the arc light for projection. Prediction of the impossible has always been difficult.

There had been many eclipses and much water had run down to the sea from student days until those memorable games of whist in his Hanover home. He played a good game; but in case of misadventure he was quick to take the blame with "mea culpa" or "peccavi" and if he thought himself very blameworthy he had a special invention, "confiteor me jaclcasse." I never knew him to find fault with his partner. Although I am glad to help the world to sobriety now, I look back without contrition upon the intervals between the rounds of duplicate whist when we sat at his hospitable table alongside of a bottle of 3% product of malt and exchanged ideas on tin apparent equality. With all his keenness he had a streak of simplicity which was the source of joyrui anecdotes wherever he taught or lectured—at Dartmouth, Princeton, Bradford, South Hadley. He told me himself of his funny lapse of memory on one of his astronomical expeditions. He went to call on a friend in Chicago. After he had ascended the steps and had rung the bell it occurred to him that he would want to give his name, and he could not remember what it was. He had no cards with him, so his only way out was to escape before anyone came to the door.

KNOWN AS TWINKLE

At Princeton lie was known as "Twinkle," a name doubly appropriate; for his eye twinkled and so did the stars. At the Princeton celebration in 1896 it naturally fell to Professor Young to introduce the distinguished men of science for honorary degrees. As he came forward on the platform the many undergraduates in the gallery greeted him with loud applause. He attributed this to the occasion rather than to himself and modestly waited for it to subside. It died down and a clear voice came from the gallery, "Twinkle doesn't hear us; give it to him again." The great audience was much amused, and Twinkle heard.

His last years were clouded with affliction; but to outward appearance he went with cheerful courage to the end.

HAINES OF RUSH MEDICAL

I never knew anyone who better combined the qualities admirable in a great teacher than did Walter Stanley Haines who for nearly forty-seven years failed the chair of Chemistry in Rush Medical College, which is now a department of the University of Chicago. He began his teaching at a time when Chemistry was only an annoyance to a medical student to be passed with the least possible trouble, and he gradually raised his department to develop needs of the highest chemical knowledge to supervise the coordinating assemblage of chemical wonders in the human body. He was only a year older than I, and I had already passed my chemistry with his predecessor whose assistant I had been, but I attended his lectures regularly for the pleasure of hearing and seeing everything so well done. As a man he was noted for his extreme courtesy and friendliness. As a lecturer he was beautifully lucid, stimulating, even elegant, in speech. In his experiments before an audience he was skillful and sure. His illustrations were simple, but they never failed; and one simple experiment that "goes" is worth any number of more complicated ones that require ten minutes each to explain why they failed. He made permanent contributions to science. In his professional work, forensic toxicology, he was thorough, conscientious and fair, so that he generally convinced and disarmed opponents, or m the exceptional cases of contest he was a match for the keenest lawyer without appearance of controversy. After his death his colleague, Dr. R. W. Webster, said, "We have lost perhaps the greatest teacher that Rush Medical College has known, certainly the most beloved member of the faculty, the man who had the deepest place in the hearts of the undergraduates. And again, "The records of the courts of almost every state in the Union contain some statements which may be directly traceable to his testimony in capital cases. And of him Dr. Norman Bridge said, "I suspect that he had made a higher record of toxicological cases, analyzed and testified about in the courts, than any other man living or dead."

A teacher never knows what he has accomplished. The effects of his work cannot be measured by the noise he has made. It would be a harmless pleasure to tell all these teachers what I think of them now.

EDMUND A. JONES About 1866

Professor Bartlett contributes another of his delightful articles to the Alumni Magazine. Below isa list of some famous teachers with whom he studied.Mrs. Ella Flagg Young.Brown School, Univ. of Chicago, Supt. ofChicago schools, Pres. Nat. Teachers Ass'n.Rev. W. A. Nichols and Mrs. Nichols.Home School for boys.Selim H. Peabody.Chicago High School, Pres. University ofIllinois.Edmund A. Jones.Lake Forest Acad., Professor Otterbein University.Daniel Crosby Greene.Lake Forest Acad., Statesman and Missionaryto Japan.Charles A. Young.Dartmouth Physicist and Astronomer.Later at Princeton.Walter Stanley Haines.Rush Med. Coll., Chemist and Toxicologist.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

May 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

May 1930 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1909

May 1930 By Robert J. Holmes -

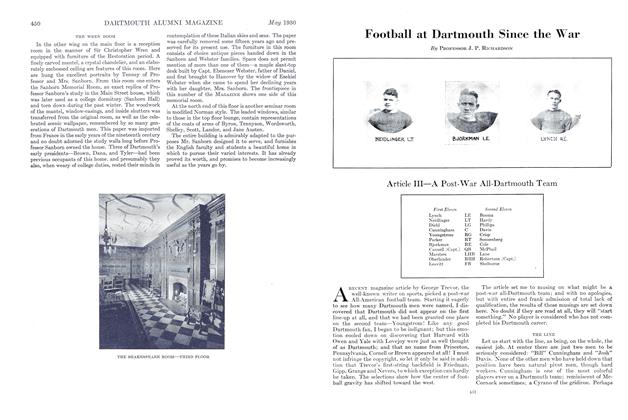

Sports

SportsFootball at Dartmouth Since the War

May 1930 By Professor J. P. Richardson -

Books

BooksECONOMICS

May 1930 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1908

May 1930 By Secretary, Arthur B. Rotch