For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

A MOMENT SNATCHED

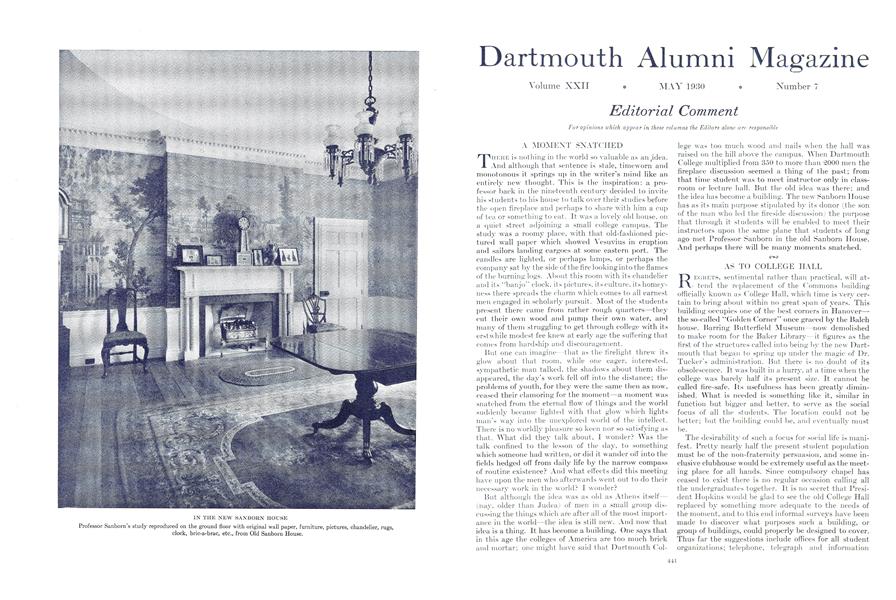

THERE is nothing in the world so valuable as an idea. And although that sentence is stale, timeworn and monotonous it springs up in the writer's mind like an entirely new thought. This is the inspiration: a professor back in the nineteenth century decided to invite his students to his house to talk over their studies before the open fireplace and perhaps to share with him a cup of tea or something to eat. It was a lovely old house, on a quiet street adjoining a small college campus. The study was a roomy place, with that old-fashioned pictured wall paper which showed Vesuvius in eruption and sailors landing cargoes at some eastern port. The candles are lighted, or perhaps lamps, or perhaps the company sat by the side of the fire looking into the flames of the burning logs. About this room with its chandelier and its "banjo" clock, its pictures, its culture, its homeyness there spreads the charm which comes to all earnest men engaged in scholarly pursuit. Most of the students present there came from rather rough quarters they cut their own wood and pump their own water, and many of them struggling to get through college with its erstwhile modest fee knew at early age the suffering that comes from hardship and discouragement.

But one can imagine that as the firelight threw its glow about that room, while one eager, interested, sympathetic man talked., the shadows about them disappeared, the day's work fell off into the distance, the problems of youth, for they were the same then as now, ceased their clamoring for the moment a moment was snatched from the eternal flow of things and the world suddenly became lighted with that glow which lights man's way into the unexplored world of the intellect. There is no worldly pleasure so keen nor so satisfying as that. What did they talk about, I wonder? Was the talk confined to the lesson of the day, to something which someone had written, or did it wander off into the fields hedged off from daily life by the narrow compass of routine existence? And what effects did this meeting have upon the men who afterwards went out to do their necessary work in the world? I wonder?

But although the idea was as old as Athens itself (nay, older than Judea) of men in a small group discussing the things which are after all of the most importance in the world—the idea is still new. And now that idea is a thing. It has become a building. One says that in this age the colleges of America are too much brick and mortar; one might have said that Dartmouth Col lege was too much wood and nails when the hall was raised on the hill above the campus. When Dartmouth College multiplied from 35O to more than 2000 men the fireplace discussion seemed a thing of the past; from that time student was to meet instructor only in classroom or lecture hall. But the old idea was there; and the idea has become a building. The new Sanborn House has as its main purpose stipulated by its donor (the son of the man who led the fireside discussion) the purpose that through it students will be enabled to meet their instructors upon the same plane that students of long ago met Professor Sanborn in the old Sanborn House. And perhaps there will be many moments snatched.

AS TO COLLEGE HALL

REGRETS, sentimental rather than practical, will attend the replacement of the Commons building officially known as College Hall, which time is very certain to bring about within no great span of years. This building occupies one of the best corners in Hanover the so-called "Golden Corner" once graced by the Balch house. Barring Butterfield Museum now demolished to make room for the Baker Library it figures as the first of the structures called into being by the new Dartmouth that began to spring up under the magic of Dr. Tucker's administration. But there is no doubt of its obsolescence. It was built in a hurry, at a time when the college was barely half its present size. It cannot be called fire-safe. Its usefulness has been greatly diminished. What is needed is something like it, similar in function but bigger and better, to serve as the social focus of all the students. The location could not be better; but the building could be, and eventually must be.

The desirability of such a focus for social life is manifest. Pretty nearly half the present student population must be of the non-fraternity persuasion, and some inclusive clubhouse would be extremely useful as the meeting place for all hands. Since compulsory chapel has ceased to exist there is no regular occasion calling all the undergraduates together. It is no secret that President Hopkins would be glad to see the old College Hall replaced by something more adequate to the needs of the moment, and to this end informal surveys have beer made to discover what purposes such a building, or group of buildings, could properly be designed to cover Thus far the suggestions include offices for all student organizations; telephone, telegraph and information service headquarters; central ticket offices; adequately furnished assembly and lounging rooms, such as a clubhouse would supply; facilities for billiards, bowling and other games; a general dining hall with numerous smaller dining-rooms adjacent; quarters for the Graduates' Club; and also, though probably as an annex, a theatre for the dramatic productions by The Players. It has even been suggested that there might be use for "a small chapel, or sanctuary," though of this one may be pardoned for feeling a doubt.

Since our college architecture has crystallized in the New England-Georgian style, it is a safe prediction that the new College Hall will take that general form when it comes pace those few who insist that there can be too much of this type of building and that we are running the risk of architectural monotony. "Unity in variety" however isn't an impossible watchword, and the outstanding character of this location clearly demands something distinctively handsome as well as useful to perpetuate the fame of the Golden Corner.

Whence the means for erecting such a building will come no one can say but at Dartmouth such things have acquired the welcome habit of arriving when least expected. For the moment it is merely the idea to be ready with a well-matured plan to put into execution when the time shall be ripe.

MOVING THE TUCK SCHOOL

THERE is room for a variety of opinions concerning the segregation of collegiate activities in general, but virtual concurrence appears to be commanded by the project to locate the Tuck school in a spot by itself, well down the Tuck Drive. To isolate a graduate department is always much easier to defend than to isolate a single class of undergraduates. Harvard's segregation of freshmen, while generally approved at the time it was first done, seems destined to give way before the growth of the Harkness plan; and at Hanover it has been suggested that if any such isolating were to be done, it would in our case be better applied to the seniors, who had had three years on the campus and who might the better spend their closing year away from it at least with less detriment than would be the case with newcomers to the scene.

When it comes to the associated schools devoted to postgraduate work, it is easy to find good reasons for separating them from the heart of the undergraduate activity. Such will function better by themselves. It is easily possible also to suppose that the College will be the better for confining campus activities entirely to those who are still of undergraduate status. In any case it will be advantageous to the Tuck school to be away from the distractions of campus life and to feel an added sense of its own distinct unity exceeding what has been possible hitherto. The same considerations apply to any postgraduate department the Medical school, the Thayer school and so forth in almost equal degree. Dartmouth is not a university, but it does have certain associated schools devoted to highly specialized work of a serious sort, whereof the Tuck School of Business Administration and Finance is the most prominent at present. The steady growth of this feature of the College has justified its acquisition of a site and habitation all its own, and that in turn should greatly enhance its usefulness.

EDUCATION AMONG ALUMNI

CONSIDERING the vast multitudes of college graduates already abroad in the land and the annual augmentation of their numbers, it seems entirely reasonable to suppose that the proportion of them capable of being reached by any system of post-graduate education, conducted under college auspices, will be small. Nevertheless the desirability of affording the opportunity to such as would welcome it and make use of it has been given increasing attention by leaders of collegiate thought and has lately brought into being an introductory survey of the field by Wilfred B. Shaw, representing the American Association for Adult Education and acting in this matter in co-operation with the American Alumni Council.

One of the earliest suggestions of this new form of activity, if not the very earliest, is to be found in an address made by President Hopkins in 1916, which Mr. Shaw cites appropriately in the opening pages of his survey. At that time Dr. Hopkins drew attention to the idea that the contribution of the college to its graduates ought to be continued in some more tangible way than at present exists, and pointed out that busy professional men tend to have less and less contact with what are broadly classified as "arts and sciences" so that interest in, or enthusiasm for, such things is likely to languish or even die, for lack of sustenance. He added:

If the college, then, has conviction that its influence is worth seeking at the expense of four vital years in the formative period of life, is it not logically compelled to search for some method of giving access to this influence to its graduates in their subsequent years! The growing practice of retiring men from active work at ages from sixty-five to seventy, and the not infrequent tragedy of the man who has no resources for interesting himself outside the routine of which he has been relieved make it seem that the college has no less an opportunity to be of service to its men in their old age than in their youth, if only it can establish the procedure by which it can periodically throughout their lives give them opportunity to replenish their intellectual reserves. It is possible that something in the way of courses of lectures by certain recognized leaders of the world's thought, made available for alumni and friends of the college during a brief period immediately following the Commencement season, would be a step in this direction. Or it may be that some other device would more completely realize the possibilities. It at least seems clear that the formal educational contacts between the college and its graduates should not stop at the end of four years, never in any form to be renewed.

Since this suggestion was first thrown out it has been exhaustively examined by numerous educators, whose thought Mr. Shaw summarizes in his present pamphlet. It may be stated that all hands were in cordial agreement that there is a responsibility resting on the colleges to afford the opportunity for continuing education after graduating, but a natural diversity of opinions as to the most useful ways of meeting that responsibility.

Perhaps the very first thing to discover is the extent to which alumni stand in readiness to avail themselves of such opportunities when offered. As one disputant puts it, "If there is a sufficiently large number of alumni who want this service from our educational institutions it is up to the alumni organizations to prove it," by revealing just how many would voice the demand, "Don't just educate us keep us educated!"

It is entirely probable that the average graduate of a college comes to recognize in his later years that he did not make the fullest use of his opportunities while a student; the question then arises how many among the vast aggregate of college graduates would take the trouble and time to repair this defect in adult years, if the opportunity were afforded. It appears to be the consensus that while the proportion would not be great, it is likely to be found great enough to warrant the trial. One commentator who is quoted intimates that, if the number is small, part of the trouble must be in the colleges themselves, in that they did not better inspire in the graduate a hunger and thirst for further cultivation while they had him under tutelage. This we find further and quite candidly recognized where the author of the survey himself states that "the fact must be faced that only a certain proportion of our degree-holders really obtained a college education. The others might be considered equivalent to the English university 'pass men.' When it comes to guessing at what actual percentage of the alumni would make use of a serious attempt to enable them to keep abreast of intellectual matters, the conjectures appear to vary wildly from 5 per cent to a flattering 20. Such experiments as have actually been made would seem to support the idea that 5 per cent is, to say the least, the more probable figure at the outset, although hopefully as the experiments proceeded the proportion might grow.

Suggested methods of meeting the situation vary from the not unfamiliar system of providing at stated intervals lists of books to be read which deal with various forms of intellectual activity, to the maintenance of actual courses—either in conveniently scattered groups located in cities where a college has considerable numbers of alumni and overseen by college representatives, or through the medium of correspondence courses and the provision of an authoritative alumni information service available at need on request of individuals. In at least one case there has been established a brief actual session of the college itself, for alumni temporarily in residence for a single week, or possibly two, at some convenient period of the year.

Financial support, we gather, is not to be asked at least at first—from alumni making use of the facilities offered, on any basis resembling an ordinary tuition charge. Reliance is placed on the probability that the little money required at the outset could well be appropriated by the colleges; and that, with a manifestation of success, ample funds for the support of this work would be provided by generous friends of education, as always. The idea is at present clearly in its earliest stages of experiment and the Shaw survey wisely advises that whatever is done along this line be modest in scope, allowing the plan to develop from small beginnings rather than seeking to make it conform to what one might say ought to be the situation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

May 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

ArticleSome Memorable Teachers

May 1930 By Professor E. J. Bartlett -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1909

May 1930 By Robert J. Holmes -

Sports

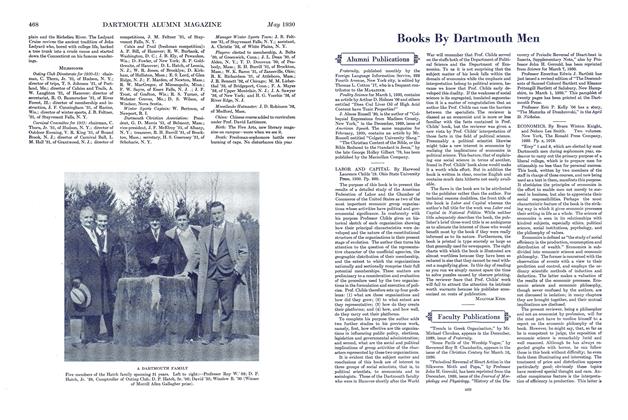

SportsFootball at Dartmouth Since the War

May 1930 By Professor J. P. Richardson -

Books

BooksECONOMICS

May 1930 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1908

May 1930 By Secretary, Arthur B. Rotch

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA LETTER FROM ED STOCKER

January, 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetter From London

May 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorSeptember

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorRuffly Speaking

NOVEMBER 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPostscript

JUNE • 1986 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

April 1945 By H. F. W.