EDUCATION begins when the self-starter replaces the crank. In awarding me a Senior Fellowship, which took away the crank, it was assumed that a self-starter, potential or embryonic, already existed. Whether or not one did exist, and whether or not I have used it to go forward, backward, or to find a shady parking place by the side of the road, is what this article will attempt to disclose.

Last June it seemed very simple. I had a concise, clear, and coordinated plan of study that I would follow, should I be fortunate enough to get one of the Fellowships. Having no predominantly strong interest in any one particular field of study, I felt that the major system, which demands concentration in a particular field, was unsuited to my needs. It has been my opinion that the major system would be greatly improved if it allowed a man to major in the work of a department as a whole, the curriculum being now divided into seven such groups, instead of some branch or subdivision of a department. That not being the case at present, I welcomed the opportunity to map out my own curriculum. As in this case criticism had to be more than merely destructive, it was essential for me to have a plan of my own that could be substituted. My plan was to combine the three departments of Philosophy, English Literature, and Comparative Literature in such a way as to effect a synthesis of the three, spreading my time equally between them. This would seem to follow to some extent the idea of the modern "Greats" at Oxford. That I failed to follow it out to any great extent is due more to my changing conception of what I should try to get out of college than to any external factor. I came to the conclusion, viewing it in the light of my immediate future, that the best possible preparation I could get in college would consist in a general widening of interests rather than the more passive acquirement of facts in a limited field. I am not belittling the importance of specialization; but I am convinced of the necessity of a horizontal view of knowledge as well as a vertical, the development to as great an extent as is possible of a catholicity of interests, the cultivation of hobbies in diverse fields. The one thing I am anxious to avoid in later life is the lop-sided type of development that is so common in the present age—the tired business man sort of existence that drives men to Paris and Pinehurst in futile attempts to whip up jaded appetites. It seems to me that the wider and more varied a man's interests, the richer and more colorful his life will be and the greater his ability to adapt himself to any given environment. Rather than dig wells in some remote corner of the field of knowledge, I would prefer to survey it as a whole and at least be aware that some relation exists between the different parts.

A DEFINITE AIM

The largest single factor in this change of attitude was the acceptance of my application for admission to Clare College, Cambridge, for next fall. This came late in October, somewhat as a surprise, as I had almost given up the idea as a result of a six months' unsuccessful campaign. As I intend to concentrate over there in English and History for two years, and after that spend three years at Law School, I expect to get all the specialization I need. The Fellowship fitted perfectly into this scheme by making it possible for me to turn my last year into an enlarged Orientation course. I have therefore made no attempt to master any one subject. (I wonder how many of my classmates think they really do know something about their major). I realize perfectly well that I am opening myself up to all sorts of criticism for being a "smatterer," "Jack of all trades," etc., etc.; and I and not saying that my course is one that would suit everybody; but in view of my own circumstances I feel that it has been the best.

In short, I would like to think that I had spent the year opening windows, instead of filling up the attic with a lot of junk that would soon be buried beneath a thick layer of dust and that I'd forget about anyway. Whether or not I shall continue to see things out of the windows depends entirely on the use I make of future opportunities.

WORKING OUT A SCHEDULE

Any attempted recapitulation of my activities during the year must necessarily be sketchy and general. By way of structural framework I have attended an average of four courses each semester, the courses being in the departments of English, Philosophy, Art (the course I took in this department was more appropriately called Universe 1), and Comparative Literature. These courses have worked together very nicely and have given me a fairly comprehensive background of information to start out with. I found especially helpful P ofessor Stewart's course in the History of English Thought, and Professor Lambuth's course in Twentieth Century Prose. Although I have usually done all the assigned reading in the various courses that I have sat in on, the bulk of my work has been done outside the curriculum. The focus-point of my reading has, perhaps, been the Tower Room, where I have averaged an hour or so a day catching up on books that I have had on my mind for a long time without having the opportunity before to read them. This chance to do considerable reading in various fields has done a lot to break down the artificial distinctions that existed in my mind between the different subjects of the curriculum—the idea that the curriculum is divided into "watertight compartments"— and has helped me to see them as component parts of the same unity.

On the subject of Art, at the beginning of the year, I was practically a blank with Baedeker my only authority. Thanks to the Fellowship, I have had the time and the incentive to make considerable progress towards acquiring an adequate basis for appreciation. The facilities of Carpenter Hall and the series of exhibitions in the gallery have been a very important addition to the College and have made it possible for every undergraduate to acquire a working knowledge and appreciation of this much neglected field. Had it not been for the Fellowship I would probably have neglected the opportunity completely. Listening to such men as C. H. Woodbury and Thomas Benton, whom the Art Department secured for short visits to Hanover, has helped me to bring the subject down out of the clouds and to lay the basework for more rational standards of criticism. Whether or not it will mean anything to me in the future will, as I have said before, depend entirely on my use of future opportunities.

In the field of music the College is relatively undeveloped, but I have tried to make the most of such opportunities as there are, especially the Concert series. As I have always liked Wagner, the Fellowship has given me the chance to do some work on him, supplemented by visits to the Metropolitan during the vacations and an intended two-weeks' stay in Bayreuth next summer.

One of the principal advantages of the Fellowship is that when some matter of unusual interest has developed it has been possible for me to postpone all other work and devote myself to that exclusively, instead of trying to keep up with daily preparation for quizzes and papers at the same time. This is particularly helpful in the case of visiting lecturers. When Lewis Mumford gave a series of four lectures in Hanover last fall, for example, I was able to take time off beforehand to read his books, so that I could listen to him with some degree of intelligence.

MEANS CHANGE OF ATTITUDE

But the most important gain of the Fellowships, for me, has not so much consisted on things learned as it has in change of attitude. In my first paragraph I said that it took away the crank. By that I mean that it took away what for me had been the principal incentive for hard work—the lure of high grades. Education based on this kind of a standard is so much water off a duck's back. The studies of my first three years lacked unity and depth because I was too wrapped up in grades and the filling of requirements to worry about anything else. If it hadn't been for the Fellowship I would probably have kept on this year in much the same fashion. The Fellowship did two important things: it showed me that study and pleasure could be combined to the best advantage of both, and it taught me to judge things in terms of their real significance for me, personally. There is at present a good deal of confusion between means and ends, a course is regarded as a thing by itself, something that has to be passed, while the possibility that it may contain some real contribution to the future wellbeing of the individual is often overlooked.

I am not yet certain as to the part a liberal education should play in a man's vocation. I have not concerned myself with that side of it. It seems to me that in a man's business or profession a liberal education should be a counteracting rather than a directly assisting influence. More than any other age, this is the age of specialization; a man has to specialize in some minute branch of human affairs to find his place in the economic scheme. Out of this necessary specialization is apt to come a one-sided development. This, it seems to me, can best be counteracted be the correct use of leisure time. In art, which treats life as a whole rather than in its myriad fragments, is found the most effective remedy. The development of hobbies or interests in any field of art should therefore by strongly encouraged by the College. The Fellowship has given me a real chance to get started along this line.

Although the year has been an extremely pleasant one, it is one that is more concerned with the future than the present. Fifty years from now, perhaps, I shall be able to give a truer estimation of the value of the Fellowship.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

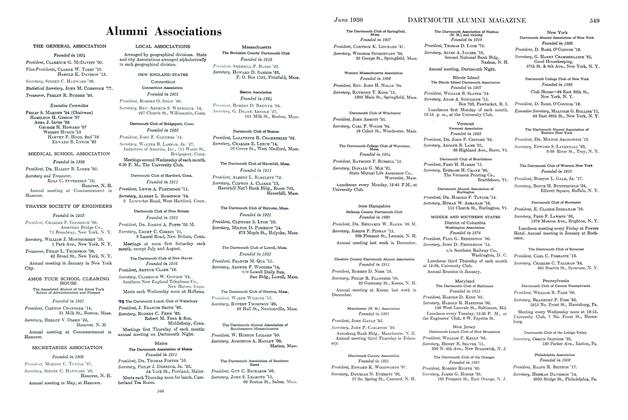

ArticleAlumni Associations

June 1930 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Indians

June 1930 By Leon B. Richardson -

Article

ArticleThe Use of Leisure

June 1930 By Nelson A. Rockefeller -

Article

ArticleA Student on His Own

June 1930 By H. S. Embree -

Article

ArticleTrustee Meeting

June 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1930