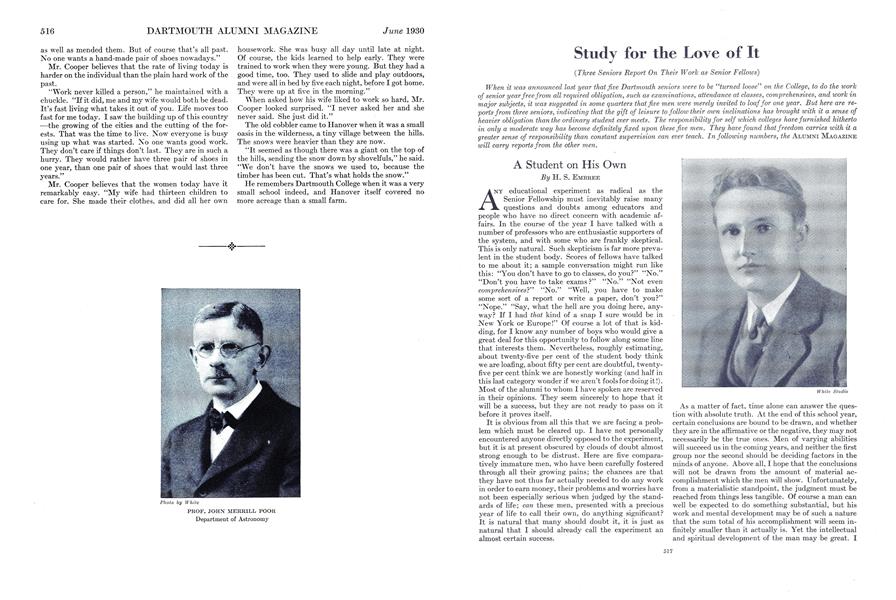

(Three Seniors Report On Their Work as Senior Fellows)

When it was announced last year that five Dartmouth seniors were to be "turned loose" on the College, to do the workof senior year free from all required obligation, such as examinations, attendance at classes, comprehensives, and work inmajor subjects, it was suggested in some quarters that five men were merely invited to loaf for one year. But here are reports from three seniors, indicating that the gift of leisure to follow their own inclinations has brought with it a sense ofheavier obligation than the ordinary student ever meets. The responsibility for self which colleges have furnished hithertoin only a moderate way has become definitely fixed upon these five men. They have found that freedom carries with it agreater sense of responsibility than constant supervision can ever teach. In following numbers, the ALUMNI MAGAZINEwill carry reports from the other men.

ANY educational experiment as radical as the Senior Fellowship must inevitably raise many questions and doubts among educators and people who have no direct concern with academic affairs. In the course of the year I have talked with a number of professors who are enthusiastic supporters of the system, and with some who are frankly skeptical. This is only natural. Such skepticism is far more prevalent in the student body. Scores of fellows have talked to me about it; a sample conversation might run like this: "You don't have to go to classes, do you?" "No." "Don't you have to take exams ?" "No." "Not even comprehensives?" "No." "Well, you have to make some sort of a report or write a paper, don't you?" "Nope." "Say, what the hell are you doing here, anyway? If I had that kind of a snap I sure would be in New York or Europe!" Of course a lot of that is kidding, for I know any number of boys who would give a great deal for this opportunity to follow along some line that interests them. Nevertheless, roughly estimating, about twenty-five per cent of the student body think we are loafing, about fifty per cent are doubtful, twenty- five per cent think we are honestly working (and half in this last category wonder if we aren't fools for doing it!). Most of the alumni to whom I have spoken are reserved in their opinions. They seem sincerely to hope that it will be a success, but they are not ready to pass on it before it proves itself.

It is obvious from all this that we are facing a problem which must be cleared up. I have not personally encountered anyone directly opposed to the experiment, but it is at present obscured by clouds of doubt almost strong enough to be distrust. Here are five comparatively immature men, who have been carefully fostered through all their growing pains; the chances are that they have not thus far actually needed to do any work in order to earn money, their problems and worries have not been especially serious when judged by the standards of life; can these men, presented with a precious year of life to call their own, do anything significant? It is natural that many should doubt it, it is just as natural that I should already call the experiment an almost certain success.

As a matter of fact, time alone can answer the question with absolute truth. At the end of this school year, certain conclusions are bound to be drawn, and whether they are in the affirmative or the negative, they may not necessarily be the true ones. Men of varying abilities will succeed us in the coming years, and neither the first group nor the second should be deciding factors in the minds of anyone. Above all, I hope that the conclusions will not be drawn from the amount of material accomplishment which the men will show. Unfortunately, from a materialistic standpoint, the judgment must be reached from things less tangible. Of course a man can well be expected to do something substantial, but his work and mental development may be of such a nature that the sum total of his accomplishment will seem infinitely smaller than it actually is. Yet the intellectual and spiritual development of the man may be great. I am free to admit without shame that I have done perhaps fewer hours of plugging than many men in college this year, but I am sure that I have discovered many things for myself that they have missed, and I believe that I have derived as much benefit from my senior year as anyone. I have the satisfaction of knowing in my own mind that my year has been anything but wasted.

A HEAVY OBLIGATION

Perhaps it would be beneficial to speak from now on in a more personal vein, and tell of the things which I believe I have discovered and which I have done. First of all, I see two minor and entirely subjective weaknesses in the system. In the first place, just as certain organizations are trying to make America "air-minded," I should like to make Dartmouth, as a whole, "Fellowship-minded." Aside from the skepticism of which I have spoken, there is a degree of wonderment and overemphasis on the fact that we are not required to do anything. The students can't quite assimilate the idea, and many professors have emphasized it to me in order that I shall not forget and begin to feel the weight of a defined obligation on my shoulders. This spirit is slightly infectious, and makes the time required to become acclimated to the situation slightly longer than is necessary. Certainly my first month was more wasteful than any of the succeeding months. In the second place, the fact that this is the initial year of the experiment has given me occasional slight worry. Despite all external efforts to quell the impression, I have felt that I was being rather carefully scrutinized and analyzed. I believe that is a minor conceit, but nevertheless I feel a strong obligation to "prove" something definite and worth while, it is not so much an obligation to the College Administration but to the classes which will succeed us as time goes on; perhaps if I fail the experiment, other classes will lose their opportunities. As I have said, these are both personal feelings, and rather nebulous ones at that; I have no shadow of doubt that they will clear up, because they are both caused by the newness of the experiment.

WORKING FOR ONE'S SELF

To offset these, there are a large number of general advantages. Obviously, a man is allowed to follow his own inclinations. I thought at first that in order to produce any results, I would have to work conscientiously, but I have since found that I went less than half way. It was only natural that I worked along lines in which I was interested. The result has been that my very interest in the subject has been more of a spur than any earthly sense of duty could possibly have been. I am afraid I came to Dartmouth primarily because I took my four years of college work for granted. It was "the tiling to do." Consequently, my first two years spent in fulfilling the requirements were the merest drudgery, I was restive under the discipline, and my work suffered. It was a blessing that I majored in English, it swept me off my feet. I wasn't working because I had to, I was working because I wanted to—I really liked it, and I only studied when my mood impelled me to. Work done under such ideal conditions is inevitably bound to be superior in quality, and it will do the worker infinitely more good. I was no longer working for a professor and the departmental examination, I was working with a professor for my own satisfaction. The Fellowship presents this possibility even more to me, and I am doing those things which I like most to do. I believe I can say certainly that my work is better because of it. Of course, there is the possibility that my particular endeavors may not appear important to everyone, but they are important to me, and I believe that is the purpose of the Fellowship.

The working with professors carries me further. I found the system of teaching during my freshman year was painfully impersonal, contrasted with that in high school. I wanted to know my professors better, but I found it difficult at first. Sophomore year I began to look at these men and say, "Gee, they're good guys, I'd like to talk to them." Junior year, these associations increased. But regard it as you will, there is a subtle stigma cast upon a man who talks too much with his professors: he's currying favor, "sucking around," in our lingo. The Honors System takes care of this somewhat, as does the natural affability of most of the faculty. But this year it has been ideal. I receive no grades, and I am assured my diploma, so I may talk to whom I wish, when I wish. It has been great fun. I have met many more men and have exchanged ideas with them. Do not overlook tobacco, it is a great aid to informality —we have smoked together and have found out interesting things about each other and about this interesting world in which we live. It is the ideal way to learn, for not only have I acquired facts and ideas, but most important, these men have fostered in me an energetic intellectual curiosity. I keep wanting to go on and on, for something unseen and beyond my reach. This is not wasted vitality, it is real living ambition, the kind that doesn't give up easily. There are no chance quizzes, no impending hour exams for which to cram, the work is all clear profit and very enjoyable.

THE FIELD WIDENS

Getting down to the actual facts of my work, I must admit I bit off more than I could easily chew, a healthy sign. In the first place, I have carried along my English Honors work under the able and unbiased guidance of Professor H. E. Joyce. This alone is the equivalent of three three-hour courses, and is a general survey of English literature. I have done the required reading, and more, and have written all the weekly papers excepting one. I have kept a record of my reading for the year, by means of a card file of personal criticism. I have stimulated my interest in the theatre by active participation in Players productions, and was fortunate enough to have the Experimental Theatre produce a one-act play of my own creation (though I refuse to discuss the "success" of my brain-child).

Perhaps the most important thing which has happened to me is my discovery that I know far less than I have given myself credit for knowing. I set out at the beginning of the year to write a dissertation on the work of Charles Dickens, studied from the aspect of the social conditions of his day. My present embarrassment is supreme, because one thing has led to another and the whole study has grown to such Gargantuan proportions that I must be careful not to attempt to write a history of the whole nineteenth century. When I started, it seemed a task with finite boundaries; I have paid dearly for my ignorance, because I must forget a lot of things before I can begin to write. The paper will be the result of a personally imposed task, and it will be finished some time before graduation. I do not as yet know what its dimensions will be, but it will probably be too long for anyone to bother reading. Nevertheless, it will have given me its full benefit.

One thing more, and this in support of a materialistic point of view. I expect to go into a business about which I know nothing more than the most obvious principles at present. Learning it from the ground up will require considerable independent study besides the necessary first-hand experience. I feel honestly that I can learn, independently, a great deal more than I ever could had I been schooled exclusively along the lines set by formal education. This year of looking out for myself has prepared me better for the things in the life which I am to meet. Discipline, I grant, is necessary, but I got that my first two years. I only hope that the seeds of this last ideal opportunity have been sown on fertile ground. If they have, and I have the fortune to succeed in my undertaking, I shall feel indebted to the family that raised me and to the college that trained me and showed me the way. If I fail, I shall not be able in justice to blame either of them; the fault will be entirely mine, and mine the loss.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

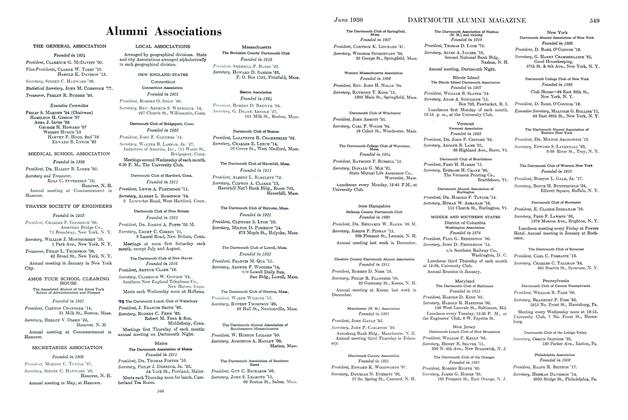

ArticleAlumni Associations

June 1930 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Indians

June 1930 By Leon B. Richardson -

Article

ArticleThe Use of Leisure

June 1930 By Nelson A. Rockefeller -

Article

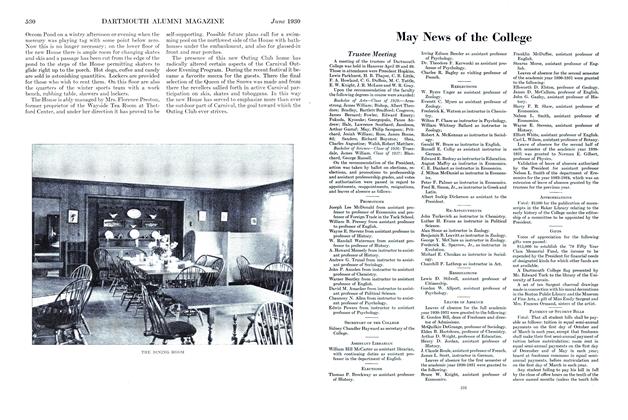

ArticleTrustee Meeting

June 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

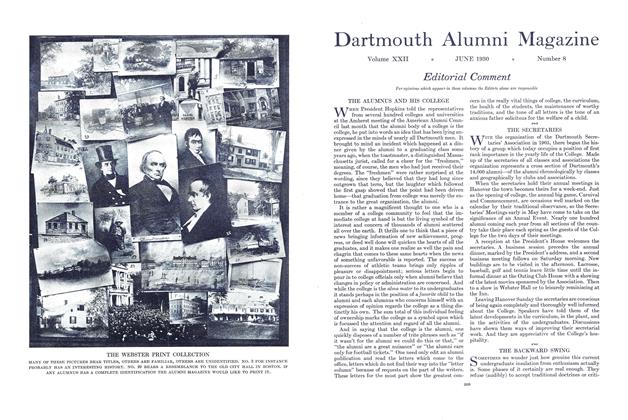

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1930 -

Article

ArticleOpening Windows

June 1930 By John French, Jr.