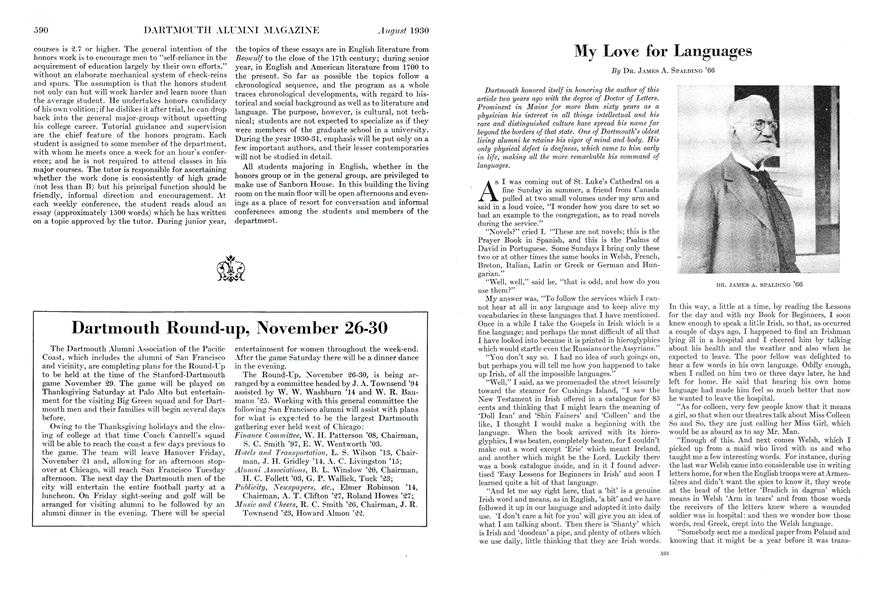

Dartmouth honored itself in honoring the author of thisarticle two years ago with the degree of Doctor of Letters.Prominent in Maine for more than sixty years as aphysician his interest in all things intellectual and hisrare and distinguished culture have spread his name farbeyond the borders of that state. One of Dartmouth's oldestliving alumni he retains his vigor of mind and body. Hisonly physical defect is deafness, which came to him earlyin life, making all the more remarkable his command oflanguages.

As I was coming out of St. Luke's Cathedral on a fine Sunday in summer, a friend from Canada L pulled at two small volumes under my arm and said in a loud voice, "I wonder how you dare to set so bad an example to the congregation, as to read novels during the service."

"Novels?" cried I. "These are not novels; this is the Prayer Book in Spanish, and this is the Psalms of David in Portuguese. Some Sundays I bring only these two or at other times the same books in Welsh, French, Breton, Italian, Latin or Greek or German and Hungarian."

"Well, well," said he, "that is odd, and how do you use them?"

My answer was, "To follow the services which I cannot hear at all in any language and to keep alive my vocabularies in these languages that I have mentioned. Once in a while I take the Gospels in Irish which is a fine language; and perhaps the most difficult of all that I have looked into because it is printed in hieroglyphics which would startle even the Russians or the Assyrians."

"You don't say so. I had no idea of such goings on, but perhaps you will tell me how you happened to take up Irish, of all the impossible languages."

"Well," I said, as we promenaded the street leisurely toward the steamer for Cushings Island, "I saw the New Testament in Irish offered in a catalogue for 85 cents and thinking that I might learn the meaning of 'Doll Iran' and 'Shin Fainers' and 'Colleen' and the like, I thought I would make a beginning with the language. When the book arrived with its hieroglyphics, I was beaten, completely beaten, for I couldn't make out a word except 'Erie' which meant Ireland, and another which might be the Lord. Luckily there was a book catalogue inside, and in it I found advertised 'Easy Lessons for Beginners in Irish' and soon I learned quite a bit of that language.

"And let me say right here, that a 'bit' is a genuine Irish word and means, as in English, 'a bit' and we have followed it. up in our language and adopted it into daily use. 'I don't care a bit for you' will give you an idea of what I am talking about. Then there is 'Shanty' which is Irish and 'doodean' a pipe, and plenty of others which we use daily, little thinking that they are Irish words. In this way, a little at a time, by reading the Lessons for the day and with my Book for Beginners, I soon knew enough to speak a Utile Irish, so that, as occurred a couple of days ago, I happened to find an Irishman lying ill in a hospital and I cheered him by talking about his health and the weather and also when he expected to leave. The poor fellow was delighted to hear a few words in his own language. Oddly enough, when I called on him two or three days later, he had left for home. He said that hearing his own home language had made him feel so much better that now he wanted to leave the hospital.

"As for colleen, very few people know that it means a girl, so that when our theatres talk about Miss Colleen So and So, they are just calling her Miss Girl, which would be as absurd as to say Mr. Man.

"Enough of this. And next comes Welsh, which I picked up from a maid who lived with us and who taught me a few interesting words. For instance, during the last war Welsh came into considerable use in writing letters home, for when the English troops were at Armentieres and didn't want the spies to know it, they wrote at the head of the letter 'Bradich in dagrun' which means in Welsh 'Arm in tears' and from those words the receivers of the letters knew where a wounded soldier was in hospital: and then we wonder how those words, real Greek, crept into the Welsh language.

"Somebody sent me a medical paper from Poland and knowing that it might be a year before it was translate into English, I picked out its meaning with a Polish Grammar and dictionary. Another physician sent me what looked like an interesting paper on Cervantes, the writer of Don Quixote, and another in Portuguese on the treatment of physicians as heretics in Brazil two hundred years ago and those in Spanish and in Portuguese I soon mastered.

"Italian I began when in college with a Berlitz handbook but did not make much progress with it until I travelled in Italy. Today I keep Italian in remembrance by reading the Prayer Book and also in talking with a fruit dealer around the corner. Not only can I speak it fairly well, but I oftentimes write letters in Italian which must be comprehended, for I never fail of an answer. I recall here an old Italian who received a letter from home, but had no one to read it for him, so he called in my services, and I not only told him all that was going on at his home, but I wrote to his friends that he was still sick in the hospital, but was better.

"French, I learned from my mother, who had travelled abroad in her youth and had an excellent knowledge of that language. German, I learned from a monk who had left his monastery in Austria in order to marry a nun who lived in a neighboring convent; they arrived in my native town in my childhood and from the head of the family I not only learned the foundations of German, but he gave proof to me that Latin was still a living language.

"Next came Greek, but in the schoolboy fashion, until I picked up later on in life a few phrases from the Greek fruit sellers of today."

In this way, as we wandered along from church I ran on from-one language to another, until finally he said, "Of what practical use is this study of languages to you as a doctor?"

"There, I can tell you something at once. A man from another state, hearing that I was a good doctor to make blind people see brought to me his blind sister. The story I have told before, but it will bear repeating, as probably unique in the medical history of this world. The man could speak English with great difficulty, his sister not a word, but both understood Russian, of which I was ignorant. I happened to notice from his garb that the man was a priest and I darted out at him this question, in Latin, 'Can you speak Latin?' 'Certainly,' said he in Latin, and we at once began to arrange in my poor Latin that he should learn from me, and then tell his sister, to open or close the eye to be operated on, to look one way or another, right, left, up or down; he was to tell her in Russian just what to do. When the time for the operation arrived, it was done by me in the fashion as suggested and ultimately the patient could see again and went home, with her glasses, rejoicing.

"Then there is my story of the Austrian officer whom we met on the road from Vienna to Venice and who told us in Latin his destination, his rank, his literary pursuits, his uniform, how much it cost him for sixty-two pairs of gloves, a fresh pair every day and thirty of them to go into the wash at the end of every month, and how much dowry a bride was obliged to provide before she could marry a lieutenant or any officer higher in rank; last of all he told me about some hospitals in Milan and Venice and mentioned one or two physicians there who were afterwards of help to me in my studies.

"Here is a curious instance of how French was of value to me medically. I was hunting up a physician who visited my native town a hundred and thirty years ago and who was born, as I heard, in the Island of Guadeloupe. I wrote there in French and was referred to the French Cure in the Province of France where this physician was supposed to have been born, and, to make a long story short, I found his baptismal certificate dated in 1747.

"During the great war, my kind wife and I paid a pension to a child in France and for sixteen years I have written letters in French to this girl and from every letter that I receive from her, I can see how I have contributed to her education by the odd questions which I have asked. This girl also knows the ancient Breton language, and from a New Testament in Breton and French I have learned a good many words which show that in ancient times the people of Breton and Wales across the Channel must have become acquainted with one another and left in each language words which are still living today.

"I like to read the Book of Psalms in different languages because I know that the translations of a good many phrases in the English translation are absurd. Now, by being able to read the same Psalms in a good many other languages I can correct curious translations in our Prayer Book and Psalms. For instance, we read of the 'wickedness of my heels surrounding me,' which is ridiculous, and which ought to be 'the wicked surround me from behind.'

" 'From the rising of the sun even unto the going down of the same' is often seen in the Psalms, but there is no such word as 'the same' in the original. All other languages say, 'From the rising of the sun unto its going down.' Of course it is the same sun, always, because we have only one, so why call it the same? The Hebrews did not!

"Again we read 'His clouds removed hailstones and balls of fire' when the real meaning is 'His clouds let fall hailstones.' Elsewhere it says, 'He shall prevent him with blessings' which is unreasonable, for nobody can understand why he should be prevented from having blessings if he should want to; but the real meaning is 'He shall come before him with blessings' and the like.

"It is pleasant also to hear of the 'strange children' for they are the gypsies of our day travelling no longer on the road with horses and wagons with a big branch of tree behind, but in the swift motor car. We like to know also that there were Irish who helped to translate the Psalms, for in one place we see that the 'ungodly is away' and again 'when lamin my health'; both phrases being borrowed from Irish.

"I was long puzzled by wondering what King David meant in saying, 'Make my enemies like unto a wheel'; until I discovered it was a treadwheel, which goes round and round until one dies of exhaustion. That is a savage way to have revenge on one's enemies.

"Here is another sentence which needs punctuation, and that you learn from comparing with the translation in other languages; 'Before I was troubled I went wrong' which should read 'Before: I was troubled; I went wrong' which makes sense.

"In one of the last of the Psalms you read of 'ten thousand of sheep brought forth in our streets' when streets should be fields, for sheep do not congregate in the public streets in great numbers.

"At the end of one Psalm you will read 'All my fresh springs shall be in me'; there those words hang on to the end of the Psalm without any explanation until, as in my old Dutch version, we see the explanation; 'this is the opening phrase of an anthem to be sung at the end of this Psalm.'

"Not to weary you with any more remarks concerning the Psalms I will finish by saying that any man, woman or child who does not read the Psalms cannot be called handsomely educated."

Here my companion interrupted me and said, "What do you think is the best way to learn languages?" and I went on to say that if you could find books in French, German, Italian or other languages, with not a single word of English and you had a teacher who could tell you what the words meant without first looking them up in a dictionary, you could get along pretty fast. An old friend of mine, after travelling in Arabia, settled in Bologna and started to teach Italians how to speak English. He would teach them thirty words at a lesson and in twenty lessons they had obtained a working knowledge of six hundred English words; with those his scholars could act as waiters at the hotels, looking out for the needs of English-speaking people who love to pass a Sunday in order to hear the service read in English. Our friend, the teacher, liked the Italians because they took off their hats to strangers; they did not spit on the streets nor walk with their hands in their pockets; he used to hire actors and actresses from the theatre to come to his apartment to read to him the newspapers of the day in order for him to catch the genuine Italian accent. This, I suggest, is a very good way nowadays, to ask the foreign fruit sellers to read you a little from their newspapers.

Talking of Bologna, I am reminded of once travelling to that city and meeting on the railroad train an officer on a furlough bound a little farther along on the road. He told us that he would soon meet some friends at a junction and that we must look out and see them. When the train stopped, we saw outside on the platform three charming Italian girls whom this gentleman kissed very courteously on each cheek. They talked a while and then the engine whistled and he kissed the three girls again on each cheek and we envied him. Soon he was aboard again with us and told us about the young ladies, and then we parted from him at Bologna.

By this time my friend from Canada and I had reached the wharf. He hoped to hear me talk some more languages again. I saw him aboard the boat for Cushings and as I trolleyed home again, I meditated more and more on languages as follows:

I like the Berlitz methods all in one language; there may be others more modern, but none more valuable for memorizing foreign words. "Jung Deutschland" is highly recommended, everything is in German; it has a useful vocabulary, German and English, but if students make up their minds not to look up the definitions they get along faster, for let it be remembered that language-study is a test of permanent perseverance; keep at it all the time if you would get your reward. Remys "First Spanish Reader" is a most agreeable book and its few Spanish musical selections are very attractive, for let it be remembered that Spanish music is delightful even in comparison with that of the German or Italian schools. The most wonderful book on Spanish is a "Short Cut" by Terry, but with its 500 pages, it is a long road to travel; it is something great for those who want to perfect themselves in that language, but right here I say, that although Spanish is good to know, for its literature, it is practically of small value, unless you plan to travel, or to live in Spanish speaking countries.

As for Latin and Greek they ought to be taught forever. I am ashamed of people when I hear them talk of "pre" and "ante" and then write pre-war and prenatal when it should be ante-war and ante-natal. When you "anted" up in the old days of poker it meant that you put up your money before the cards were dealt. That is time, and ante means before, in time: He came before I did—ante. Pre, means before in position: He came before I did—ante; and then he stood before the king—pre—and bowed. The difference between pre and ante is plain but requires thought; yet there are a good many things that are easy if you think'

Latin is invaluable to the students of French for the gender of every noun in French depends upon the gender of the noun in Latin from which it was derived.

"Nouns in er, or, o with eo, io, do and go, with dens and pons and mons and fons, are to be counted masculine."

That jingle I learned seventy-five years ago, and have never forgotten it, but where it can be found today is beyond me. There is also another rule for feminine nouns, but not so graciously poetical, and therefore less quoted.

Talking about the uses of languages, anyway, I saw the other day a Report of a congress on diseases of the eye in five languages, yes, seven, for the title of it was in Latin, and the preface of it was in Dutch and the papers were printed in French, German, English, Italian and Spanish. Members of different languages could thus understand what was going on when a paper was read in a language different from their own, and instead of sitting around as mere deaf old members "in whose mouth there is no reproach" as King David has wisely said, they could follow the speaker and be ready to stand on their feet and say something in their own language when he had finished.

Latin and Greek are still learned by the old grammatical fashion and they are worth studying. A great many people forget this and here was a distinguished man running down Latin the other day and said, as he ended, "Avoid Latin derivatives, use terse, idiomatic, virile, incisive English." At a reception later on a friend of his speaking to him in an aside, said, "Well, Bi'l, "in that remarkable sentence of yours, one word might have been Anglo-Saxon and one Greek and the other seven were Latin derivatives."

I do love to think of the man who is "affluent" because it means that no matter what he does money keeps running right into his pockets; and there is "arable" land, which means land that is not full of stones, but is easy to plow and cultivate: from the Sanskrit "Ar," a plough.

I have found Greek quite useful in asking for fruit and provisions. It is really amusing to think that "clam" is a word of four letters with us, and thirteen letters in Greek, for the same old shell-fish. The Greeks like to have you use their language. If you ask an Italian for his very lowest price it makes him smile for he is used to chaffering and bargaining while we Americans rarely condescend to beat down anybody. We pay what is asked, and then say hard words afterwards. Then, again, in the Greek there is a melody that is most charming to the ear and just as our old friend in Bologna learned Italian by listening to actors and actresses so we can learn Greek and Italian by having their newspapers read to us.

I have forgotten so far to say that plays are of much service in learning languages because they contain a great many conversational idioms which you have to learn when you meet people. Plays in Latin and Greek are rare and difficult, but those in modern-languages are rich in instruction.

Can we learn to speak languages in this country? I say it is well nigh impossible because we do not hear the words often enough. When I was the Spanish Consul I found only two Spanish speaking people in Maine. People say, "We met abroad hotel porters who could speak seven or eight different languages." And I say they should be ashamed of themselves if they couldn't, for they have every day questions put to them over and over again in the same languages until they really cannot help learning them by heart; but if you should asthose same porters to read you a book, in those seven languages you would find them wonderfully deficient.

In the midst of your study of foreign languages, keep your mind fixed on your own. Keep it as pure as you can. Use as little slang as possible. Never print it, for it offends the eye as well as the mind. There are three words that I detest, one is "auto," the second is "automobile" and the third is "outstanding" and why? Auto means self. How is your auto? In other words, How is yourself? Automobile means self-moving. Did you buy a new self-moving yesterday or are you going to buy a self-moving tomorrow? Why is it, that people will shatter their teeth and dislocate their tongue in pronouncing auto and automobile, when a motorcar means something? Why is it that a boat with a motor is a motorboat, and a truck with a motor is a motor truck, but a car is a self-mover.

Next we arrive at the word "outstanding" as if it meant something superior, and better than anything that ever was. But Roget's famous "Thesaurus of the English Language," tells us that outstanding means: Now listen! "Outstanding refers to remainders, remnants, relics, leavings, heel-taps, odds and ends, cheese parings, candle ends, off-scourings, dregs, scum, ashes, surplus, overplus, balance, revivals, and survivings." You don't find much superiority in "outstanding," according to Roget, do you?

Neither do I like "Thru." This comes from through and that comes from thorough. Now if you have done anything so well as to get through with it, it means that you have done a job thoroughly; if you are to say "thru" as a sound for imitation, in using other words of the same sound what becomes of thrust, must, bust, lust, rust, and trust; are they to be pronounced throost, moost, boost, loost, roost and troost? I tell you that bad spelling of any words is a confession of ignorance; it means that you are lazy and indifferent and "don't care" and I was brought up to say that Don't Care is a hireling who runs off and leaves the sheep fold open to thieves and wolves.

The learned professors of today, in their ignorance, say in regard to simplified spelling, "Oh, well, it makes it easier for children and foreigners to learn our language," but why should we make things easier, when we have brains to work with? It did not hurt my generation to learn words that were hard, and it would not hurt the present generation to learn the same words. If we have children who are backward in spelling, then let the words which they stumble over be chalked out large and white on a blackboard and those children tested in them day by day.

It is sad that the women of today should poke fun at our language talking of their clubs with odd names like "Chatchuso" and the "Yfere," as if they had anything to be afraid of, and that terrible name "Mardinuit," as if they planned to spend the night with their hostess; forgetting that "soir" is the proper word for evening, whilst "nuit" means the whole thing. Why poke fun at good words, why degrade our living language, why deface a good-looking word?

Every morning at school for five years we were made to listen to a choice of words from a page of the dictionary which we had learned the day before and from which the teacher read out twenty words in ordinary use. These words we had to write on a piece of paper, define, accent and hand to a monitor to be marked, I tell you, that there were few bad spellers in our school; I am one of the few remaining and I can still spell pretty well at the beginning of my eighty-fourth year.

Keep your foreign languages alive by talking daily with yourself. "I am well." "I had a good breakfast." "I hope that I shall make some money today." And so on, with ordinary conversation, in the lack of natives; talk this way to yourself, and so enrich your memory and keep your words alive.

Old Sam Johnson said that you must keep your friendships in constant repair, if you wish to live happily, and I go him one better and say that if you wish to hold on to your languages, once started, repair them daily by thinking them over and speaking to yourself with your wide open lips.

DR. JAMES A. SPALDING '66

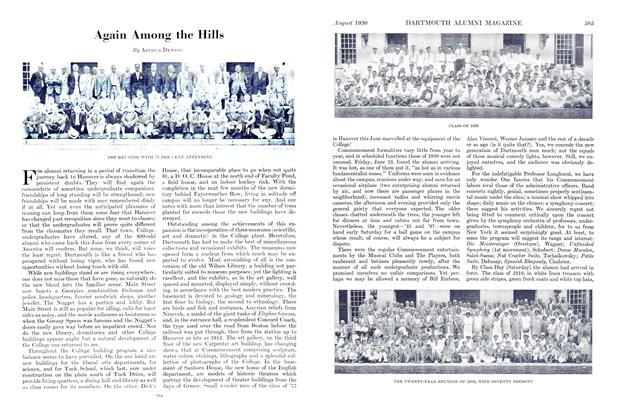

CLASS OF '67

MAIN STREET LOOKING SOUTH SHOWING THE TONTINE: ABOUT 1870

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

August 1930 By Frederick W. Andres -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

August 1930 -

Article

ArticleMidsummer Musings

August 1930 By Phil Sherman -

Article

ArticleDebating at Dartmouth

August 1930 By E. V. Simrell, Faculty Advisor -

Article

ArticleAgain Among the Hills

August 1930 By Arthur Dewing -

Article

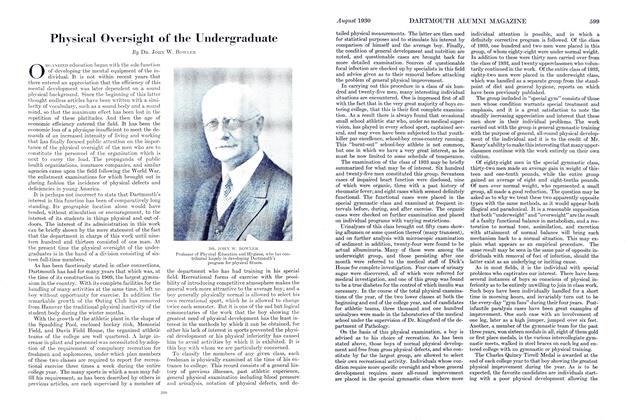

ArticlePhysical Oversight of the Undergraduate

August 1930 By Dr. John W. Bowler

Article

-

Article

ArticleNAVY-HANOVER RELATIONS CORDIAL, SURVEY DISCLOSES

January 1943 -

Article

ArticleValedictory to the College

August 1946 -

Article

ArticleThird Century Professorship Established

JULY 1969 -

Article

ArticleThe Alumni Council for 1973-74

October 1973 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

April 1945 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleLibrary Report

March 1952 By R. L. Allen '45