For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

ONE MORE COMMENCEMENT

DARTMOUTH has closed one more year of collegiate activity and has sent forth one more class into the world of gainful activity not her largest class, but a close second thereto in point of numbers after a year not marked by any very sensational event to differentiate it from other years. It was, however, a most gratifying year, in every way save one the deplorable incident being the untimely death of Eugene F. Clark, long-time secretary of the College and of the various subsidiary organizations incident to its administration. Apart from that one loss, it has been a year to bring rejoicing to the heart of those who delight to see Dartmouth realizing more fully with the lapse of time the opportunities which lie open before her.

Among the notable incidents of the past few months may be cited the gift of a million dollars by Mr. George F. Baker to finance the upkeep and operation of the Baker Library; the completion and opening of the Sanborn House as headquarters for the English department; the completion of the enclosed hockey-rink, which is relied upon to make for a greater excellence of winter sports; the decision to move the College church—as it is usually but somewhat misleadingly called—from its ancient site to the spot so long occupied by the Rollins Chapel; the virtual finishing of the new Tuck School plant on the Tuck drive; and the completion of work on various other buildings, not forgetting the demolition of Culver Hall.

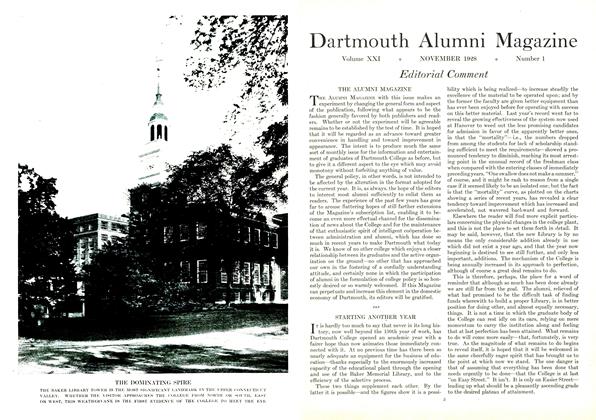

The plan to move the old "white church" which suggestion, rather surprisingly, came from the church to the College rather than vice versa is bound to be variously received, but with the process of time will probably be accepted by all concerned as an improvement. It will cause regret in many breasts to see Rollins Chapel disappear, as disappear it must in the march of progress, because to those of us who were reared in the days of compulsory chapel attendance it was a spot associated with many precious memories. But architecturally and in many other ways the change will be all for the good. The chapel was at no time in harmony with the other buildings of the original row; and the removed church, when placed to balance Reed Hall as it is proposed it shall be, is certain to be more in keeping. In a year or two it will probably be forgotten by every- body that it was ever elsewhere, and the opening of the vista to Sanborn House is unquestionably destined to make a great improvement in the general appearance in the north side of the campus. The new site will enable the creation of a Parish House, to which the church has long aspired, but which had no room for its realization while the church stood on the old corner.

To such as feel a distinct qualm over this radical change in Hanover's topography it is perhaps in order to recommend a suspension of judgment until the changes have been completed and have fitted themselves into the new picture as permanencies. This particular change has come hard, and it is certain to reach well in among the heart-strings of many generations of Dartmouth and Hanover people; but it has come to be the conclusion of all most directly concerned that only thus can the interests of all be adequately reconciled. Those of us to whom the matter is merely of sentimental moment may well defer to those more intimately concerned, whether as the active members of the Church of Christ at Hanover, or as present members of the College community.

Another interesting feature of the year has been the experiment initiated in 1929-30 of selecting five outstanding seniors to be "guests of the College" throughout the year, paying no fees and owing no fixed duties, but privileged to pursue education according to their own inclinations with whatever assistance from the College they might choose to seek. This experiment is likely to spread among the colleges of the country if it appears to justify itself; and it is fair to say that the year just closed has given every indication that it will do so. The extent to which it can be applied is necessarily limited. Half a dozen young men of peculiarly exalted capacities may well be as many as can be expected to justify such a measure of confidence in any class of rising four hundred boys. But insofar as such prove capable of self-improvement unhampered by the slower pace of the mass of their fellows it is beyond doubt desirable to relieve them of restrictions and give them a free field, provided this produces no unfavorable reaction among such as must still compose the rank and file. It is no small test of personality and character.

ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY-ONE YEARS

ENORMOUS changes have affected the world since the first Dartmouth Commencement, one hundred and sixty-one years ago. Specialization has become the order of the day. In many educational processes as in other phases of human activity the trend has been for some time toward specialization. The great vocational schools, the universities having as their principal motive training for the professions, occupy a large place in the educational life of the country.

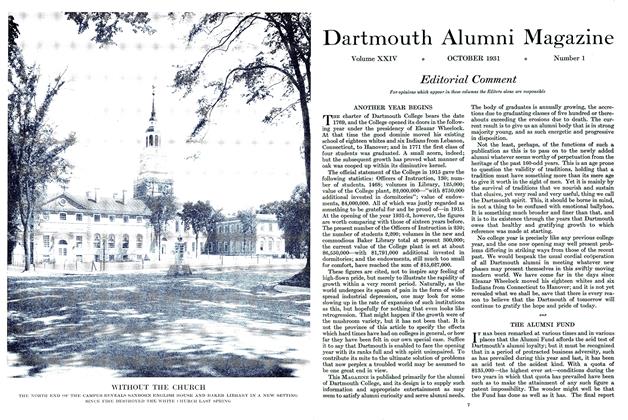

Dr. Wheelock founded Dartmouth in 1769 as a Liberal Arts college. Its position as such has not changed in more than a century and a half of revolutionary progress in the mechanical arts. It still stands as a powerful influence in the old Liberal Arts tradition. Older than the nation itself, Dartmouth has given to youth of the land opportunities for laying broad cultural foundations for their later careers. Isolated in its New Hampshire village, Dartmouth will carry on this tradition for centuries to come.

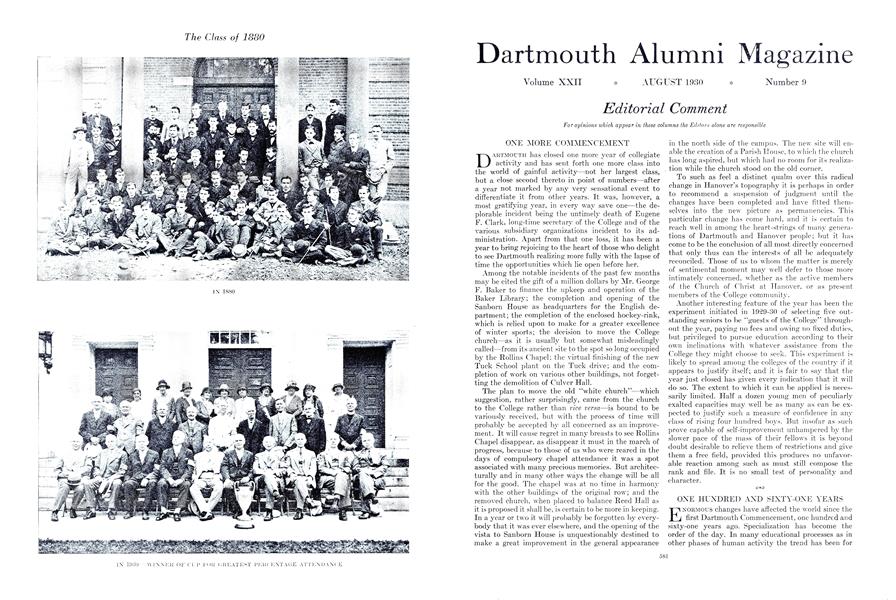

One hundred and sixty-one years ago a company of gentlemen, headed by John Wentworth, Royal Governor, made their way from Portsmouth through trackless forests to the first Commencement. Four young men were graduated in that first class. Hundreds of Dartmouth alumni yearly speed to Hanover by train, automobile, and airplane. They join with parents and friends, with trustees and faculty, to give more than four hundred graduating seniors their congratulations for a task accomplished, to welcome them into the Dartmouth Fellowship, and to rejoice that these youngest sons are equipped, as were those four first sons in 1771, with a foundation for good living and useful citizenship in the society to which they go.

THE PHI BETA KEY

AN item of collegiate news during the early spring prompted the following good humoredly sarcastic comment from the erudite Springfield Republican:

The Rutgers University senior class has voted by 132 to 38 a preference for a Phi Beta Kappa key over a 'varsity "R." Haven't the teams been doing well lately?

Notoriously the success or failure of the teams has nothing to do with such votes as this. It may be that here and there some senior class has had the temerity to speak right out in meeting and vote, 132 to 38, that a 'varsity letter is greatly to be preferred to a Phi Beta Kappa key; but after a profound search of our recollections we fail to recall such an instance and doubt that any exists. Presumably if it ever did happen it would not pass unnoticed, however.

The fact is, of course, that a Phi Beta key really is a much more desirable possession in the long run than a 'varsity letter; and college seniors have far too much sense to go on record publicly in favor of so dubious a proposition as that the value lies the other way about. It sometimes appears that while this righteous judgment is overwhelmingly supported as an academic matter, the same voters turn around and choose to the most coveted positions in the Commencement exercises men whose celebrity rests on athletic achievements rather than on scholastic prowess; but that in no way affects the validity of the previous vote and in a way it squares the yards. The conspicuous scholars have their reward. They figure as valedictorians, salutatorians and Commencement orators; and the incidental functions of Class Day rather appropriately fall to the men whose eminence and popularity arise from other activities. No one underestimates the 'varsity letter, and probably many a Phi Beta member secretly wishes he had one if he hasn't, which is not necessarily the fact. But when we are voting on the comparative worth of such baubles we usually have in mind something more extensive than the brief season of athletic glory and are looking at the problem in the large.

TO ROW OR NOT TO ROW

IT has been interesting to note the reaction of alumni to the recent suggestion that Dartmouth enter or rather re-enter the ranks of the rowing colleges. As is the case with every other new thing, or thing about which no one has thought very much, this project has evoked the inevitable amount of criticism ranging from skepticism to downright hostility, perhaps best typified by the detailed consideration embodied in a recent report of the Dartmouth Club of New York. The arguments there advanced against the idea of a Dartmouth crew appear to base themselves chiefly on the fact that rowing as a sport involves all expense and no revenue.

It may be doubted that this alone is conclusive, however. The same thing is true of other sports, which the College already does countenance but which probably cannot be rated as useful as rowing would be in bringing the institution into favorable public notice. The fact is that almost none of the other organized sports even begin to pay their own way and must be financed from the receipts of football in the autumn. One may accept as a postulate the certainty that rowing wouldn't pay its own keep—probably wouldn't bring in offsetting revenue of any amount worth considering—and would be a rather expensive activity to embark upon. The question then arises whether or not it is still worth the doing, for other reasons than the financial just as so many other college sports have been decided to be. It should not be forgotten that the decision in the other rowing colleges, where the same conditions obtain, has been favorable and that about the last thing any of them would dream of abandoning is the crew.

Dartmouth used to row, but that was so far back in history that comparatively few now living recall the days of the sport's greatness. There would be no talk of reviving it now, we suspect, if it were not for the fact that motors have suddenly brought within easy reaching distance the waters of Lake Mascoma. Rowing on the Connecticut river involved too many problems, chiefly because of the strong current and the variable volume of the stream. So long as Lake Mascoma was an hour or more away, its suitability as a training and racing place was unsuspected. Now that it is possible to reach that sheet of water in something like twenty minutes from Hanover, the aspect of the case is different.

It is not the present purpose to defend the idea of our having a crew, so much as to protest against the too hasty dismissal of the plan as impracticable or even absurd. The latter it certainly is not. It is no more ridiculous for Dartmouth to enter upon this internationally famous sport than for Harvard, or Yale, or Cornell, or M. I. T. It is easy enough to wax humorous or cynical over any new proposition like this, but really the possibilities seem to us sufficiently great to make it inadvisable to dismiss the notion with an airy wave of the hand. It will be well to have the proposal seriously discussed, and above all it is desirable that the suggestion be received with at least an open mind.

WHY NOT A YEAR OFF?

PRESIDENT Hopkins has had no vacation of real magnitude in the past 14 years practically no time away from the anxieties of his job, save such as was demanded by recuperation from illness. He has labored early and late in a multitude of different fields to further the interests and growth of Dartmouth, with what success we all know. Meantime it is the rule for professors everywhere to have one year off in seven, and experience proves it to be a wise provision, promoting efficiency and contentment all around.

There's no virtue in working a superlatively valuable man to death. The College would miss President Hopkins sorely if he were given a full year's leave, of course; but it would miss him far more sorely if, by driving him too steadily and too long, it forced his untimely relinquishment of the helm. It is understood that for some time the Trustees have been anxious to arrange for a real vacation, involving complete freedom from the detailed cares of administration of the College, for the President; and the apparent well-being of the institution at the moment seems to make this a time when such absence can best be afforded. The building program is in such shape now that it can be left to one side for at least a year, as has been indicated elsewhere. The College as a whole is under such gratifying momentum that it can be trusted to run itself for a twelve month far more securely than at any other recent period. If the President is ever to have a year off, could there be a better time?

THE "SHORTS" INTERLUDE

IT is unprofitable, no doubt, to get much steamed up over student ideas as to the best fashion for clothing the male leg. This topic has been brought to the fore within recent weeks by the sudden advent of a passion at Hanover for donning "shorts" brief trouserings, such as in Great Britain are affected chiefly by Boy Scouts, but are occasionally worn by older men on hiking trips. That the custom of wearing such gear with more formal dress has made headway elsewhere than in America chiefly in Hanover is open to doubt; but as always it is futile to dispute over matters of taste. In fact disputing over this particular one would presumably have the usual effect of making the exponents of the new fashion all the more determined to exploit it.

The male trouser is at best an ugly garment. Custom decrees that men go about with their legs encased in long tubes of cloth, which bag at the knee and require the frequent attention of the pressers. Thus far the ordinary trousers defy the sculptor who attempts to make a famous statesman immortal by depicting him in deathless stone, clad in the garb which fashion decrees man shall wear. Possibly a statue of Cicero in his toga looked similarly queer to contemporary eyes as would a statue of a senator from Massachusetts if portrayed in marble trousers, neatly creased down front and back. But togas went out of style years ago, and romance began to exalt that voluminous garment. Hence the tendency to clothe the effigies of Idaho statesmen in clothes they do not actually wear in life in Roman robes, or in flowing gowns of academic cut rather than crystallize them for all time in the sort of things custom demands they use in appearing on the street. Now and again some peculiarly venerated figure such as that of Lincoln is chiseled wearing a full suit of clothing such as obtained in 1861, the trousers having the appearance of having lately journeyed across the continent in a loosely packed trunk. But there's no blinking the fact that what a less elegant day called "pants" are ugly garments, and the temptation toward variants is always strong. Hence the growth in popularity of the plus fours, and the more recent ebullition of a passion for shorts which leave a considerable amount of bare leg exposed to public view.

Each to his taste—but it may be said in passing that the male leg is not usually a thing of great beauty. One recalls that the possession of admirable ones figured as among the major attractions of Sir Willoughby Patterne.

Unkind comments have been prompted by the Dartmouth fashion of last spring—one professor in a rather inconsiderable institution of learning being heard to remark that Dartmouth was "rural-minded." Just how the wearing of shorts connotes the bucolic is not clear, unless it be that shorts are not commonly seen along Broadway and Park Avenue; but neither are they reported to be of frequent occurrence in Coos and Aroostook. On the whole it may be set down as a passing fancy of boys who rather enjoy doing something of startling novelty now and then, en masse, and who might be much more harmfully engaged than in seeking to invent a new kind of covering, or uncovering rather,, for the nether limb.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMy Love for Languages

August 1930 By Dr. James A.Spalding '66 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

August 1930 By Frederick W. Andres -

Article

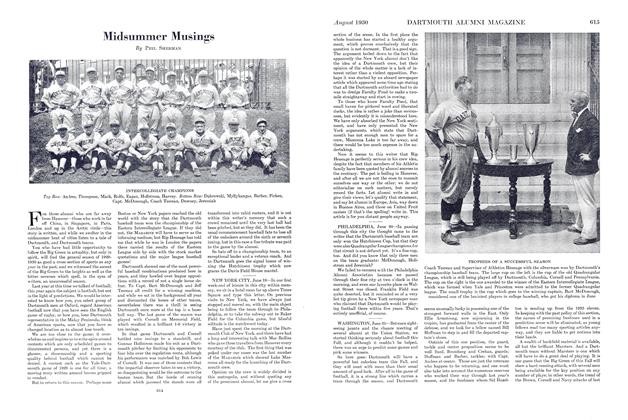

ArticleMidsummer Musings

August 1930 By Phil Sherman -

Article

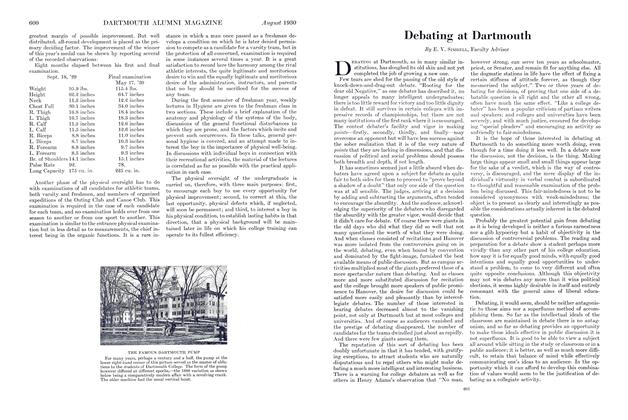

ArticleDebating at Dartmouth

August 1930 By E. V. Simrell, Faculty Advisor -

Article

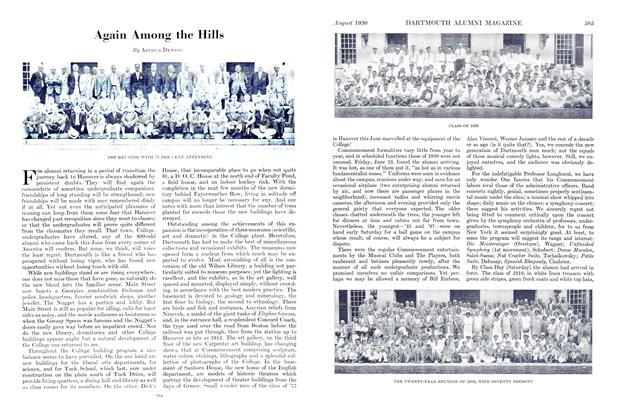

ArticleAgain Among the Hills

August 1930 By Arthur Dewing -

Article

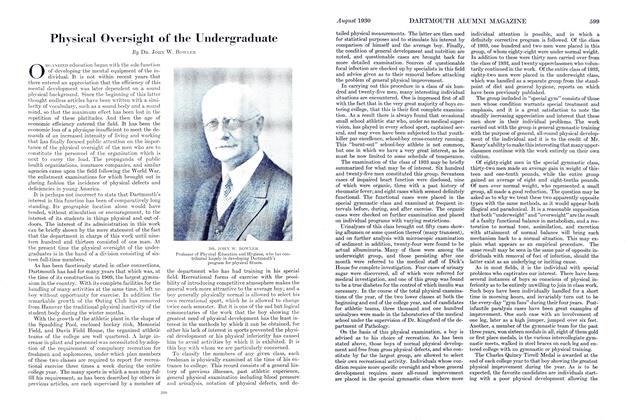

ArticlePhysical Oversight of the Undergraduate

August 1930 By Dr. John W. Bowler

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1928 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

JUNE 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

OCTOBER 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPress

December 1945 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editorthe magazine has received a great many calls from alumni asking for an interpretation of the Cole affair.

APRIL 1988