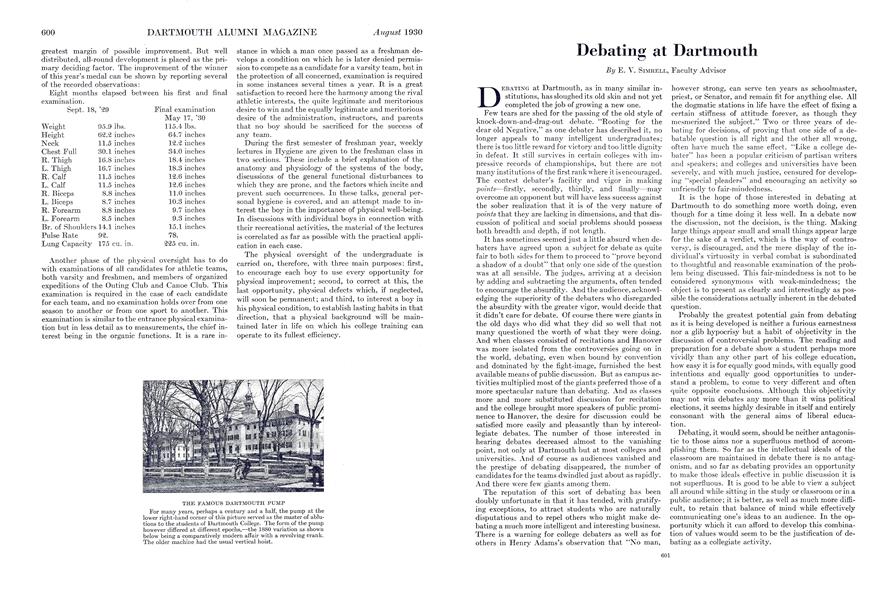

DEBATING at Dartmouth, as in many similar institutions, has sloughed its old skin and not yet completed the job of growing a new one.

Few tears are shed for the passing of the old style of knock-down-and-drag-out debate. "Rooting for the dear old Negative," as one debater has described it, no longer appeals to many intelligent undergraduates; there is too little reward for victory and too little dignity in defeat. It still survives in certain colleges with impressive records of championships, but there are not many institutions of the first rank where it is encouraged. The contest debater's facility and vigor in making -points—firstly, secondly, thirdly, and finally may overcome an opponent but will have less success against the sober realization that it is of the very nature of points that they are lacking in dimensions, and that discussion of political and social problems should possess both breadth and depth, if not length.

It has sometimes seemed just a little absurd when debaters have agreed upon a subject for debate as quite fair to both sides for them to proceed to "prove beyond a shadow of a doubt" that only one side of the question was at all sensible. The judges, arriving at a decision by adding and subtracting the arguments, often tended to encourage the absurdity. And the audience, acknowledging the superiority of the debaters who disregarded the absurdity with the greater vigor, would decide that it didn't care for debate. Of course there were giants in the old days who did what they did so well that not many questioned the worth of what they were doing. And when classes consisted of recitations and Hanover was more isolated from the controversies going on in the world, debating, even when bound by convention and dominated by the fight-image, furnished the best available means of public discussion. But as campus activities multiplied most of the giants preferred those of a more spectacular nature than debating. And as classes more and more substituted discussion for recitation and the college brought more speakers of public prominence to Hanover, the desire for discussion could be satisfied more easily and pleasantly than by intercollegiate debates. The number of those interested in hearing debates decreased almost to the vanishing point, not only at Dartmouth but at most colleges and universities. And of course as audiences vanished and the prestige of debating disappeared, the number of candidates for the teams dwindled just about as rapidly. And there were few giants among them.

The reputation of this sort of debating has been doubly unfortunate in that it has tended, with gratifying exceptions, to attract students who are naturally disputatious and to repel others who might make debating a much more intelligent and interesting business. There is a warning for college debaters as well as for others in Henry Adams's observation that "No man, however strong, can serve ten years as schoolmaster, priest, or Senator, and remain fit for anything else. All the dogmatic stations in life have the effect of fixing a certain stiffness of attitude forever, as though they mesmerized the subject." Two or three years of debating for decisions, of proving that one side of a debatable question is all right and the other all wrong, often have much the same effect. "Like a college debater" has been a popular criticism of partisan writers and speakers; and colleges and universities have been severely, and with much justice, censured for developing "special pleaders" and encouraging an activity so unfriendly to fair-mindedness.

It is the hope of those interested in debating at Dartmouth to do something more worth doing, even though for a time doing it less well. In a debate now the discussion, not the decision, is the thing. Making large things appear small and small things appear large for the sake of a verdict, which is the way of controversy, is discouraged, and the mere display of the individual's virtuosity in verbal combat is subordinated to thoughtful and reasonable examination of the problem being discussed. This fair-mindedness is not to be considered synonymous with weak-mindedness; the object is to present as clearly and interestingly as possible the considerations actually inherent in the debated question.

Probably the greatest potential gain from debating as it is being developed is neither a furious earnestness nor a glib hypocrisy but a habit of objectivity in the discussion of controversial problems. The reading and preparation for a debate show a student perhaps more vividly than any other part of his college education, how easy it is for equally good minds, with equally good intentions and equally good opportunities to understand a problem, to come to very different and often quite opposite conclusions. Although this objectivity may not win debates any more than it wins political elections, it seems highly desirable in itself and entirely consonant with the general aims of liberal education.

Debating, it would seem, should be neither antagonistic to those aims nor a superfluous method of accomplishing them. So far as the intellectual ideals of the classroom are maintained in debate there is no antagonism, and so far as debating provides an opportunity to make those ideals effective in public discussion it is not superfluous. It is good to be able to view a subject all around while sitting in the study or classroom or in a public audience; it is better, as well as much more difficult, to retain that balance of mind while effectively communicating one's ideas to an audience. In the opportunity which it can afford to develop this combination of values would seem to be the justification of debating as a collegiate activity.

The change in the purpose of debating from that of competitive exhibition to that of free discussion has prompted two mutually complementary innovations in Dartmouth's forensic program, one a new form of debate and the other a new kind of audience.

CROSS-EXAMFNATION DEBATE

It has been said that modern weapons of warfare have eliminated the virtue of primitive combat, which could be depended upon usually to give the victory to the better side. The cross-examination debate is intended to restore this virtue to debating, so far as debating remains combative, by substituting hand-tohand combat for long-range gas attacks. It is a modification of what is known as the Oregon plan of debate, a combination of a Socratic dialogue and a court trial, except that both sides are expected to seek truth and justice.

This is how the plan works: The debate is opened by an affirmative speaker who presents in a speech of about fifteen minutes the entire constructive argument of his side. Then a speaker for the negative is allowed the same time to discuss the subject as he sees it. By that time everybody is fairly well oriented in the considerations involved in the question. Then for twenty minutes or so a second man on the negative side crossexamines the affirmative speaker, and is followed by a second man on the affirmative side who cross-examines the negative speaker. Then the cross-examiners are given about five minutes each to summarize, not their own assertions, but what their witnesses have actually given them in answer to questions.

The time-allowances are varied on occasion but the proportions are maintained. The cross-examination, as the plan is used at Dartmouth, is made the dominant part of the debate and is intended not only to expose any weaknesses in the witness's direct argument but also to gather from him new or neglected evidence against his own side. This locates the element of controversy where it belongs, in the subject debated instead of in the opposition of the debaters. If the witness balks or evades there is a judge to call him to order; if he attempts to obscure issues, inflate arguments, or suppress facts, the cross-examiner makes him expose himself. On the other hand, if the cross-examiner tries to be tricky the witness acts as a check upon his ingenuity. The witnesses do not have to take an oath; the situation puts a premium upon soundness and straight thinking instead of upon bombast and distortion. It is rather gratifying to observe how difficult it is for a great deal of apparent eloquence to survive a good cross-examination.

The first cross-examination debate in Hanover was held this spring, when Harvard and Dartmouth debated the subject of censorship before an audience of nearly two hundred. The debates with Oxford and Cambridge and with Smith will presumably continue indefinitely to consist of speeches only, but the popularity of the cross-examination method where it has been used will probably lead to its use in an increasing portion of our debates. Last year it was very successful in debate with Harvard and Columbia, away from Hanover, and in a number of off-campus debates.

OFF-CAMPUS DEBATES

These off-campus debates are the other important innovation in Dartmouth's program of debating. Their object is to take debates to other than campus audiences, to audiences that are less interested in the result of the debate than in hearing a lively and well-informed discussion. Largely through the assistance of alumni in making arrangements, these debates are held before Rotary and Iviwanis clubs, women's clubs, Chambers of Commerce, schools, and various other organizations interested in current problems.

Subjects are chosen for their timeliness or for their perennial importance or for both. An effort is made to determine the subjects that the audiences will really want to hear discussed, and a list of these subjects is submitted to each organization so that they may choose the one they prefer. This year's list, for example, includes censorship, trial by jury, religious organizations in politics, and the limitation of higher education to those of special capacity. A new list is to be prepared for each year's program, and suggestions for new subjects are always welcomed.

The debates themselves are informal and are usually followed by open-forum discussions. The variety and maturity of the audiences, the greater interest in the subjects of the debates, and the general character of the occasions make this experience on the whole much more valuable to the debaters than ordinary intercollegiate competition. At the same time, the organizations that have sponsored debates have reported that they found them excellent entertainment.

Last year, the first in which any serious effort was made to promote this program, debates were held before off-campus audiences in Montpelier, Lebanon, White River Junction, Newport, Claremont, Woodstock, and Philadelphia, Pa. So far this year debates have been either held or scheduled to be held in Lebanon, Windsor, Woodstock, Bellows Falls, Brattleboro, Franklin, White River Junction, Littleton, New York, and Philadelphia; by the time this is published several more will likely have been added to the list, and about twenty students will have participated in the debates. These off-campus debates will probably continue to grow in number and importance as compared with intercollegiate debates.

As I began by saying, debate at Dartmouth has not yet by any means completed its process of renovation. It is open to all of the criticisms that are applicable to most activities in a state of transition. But the conditions which once nourished debating have given way to conditions which require new purposes and new methods. It is realized that the past glories of debating are impossible to recover in the present, and it is hoped that debating may be made a more reasonable activity if a less aggressive one, and in the long run more profitable to both debaters and audiences.

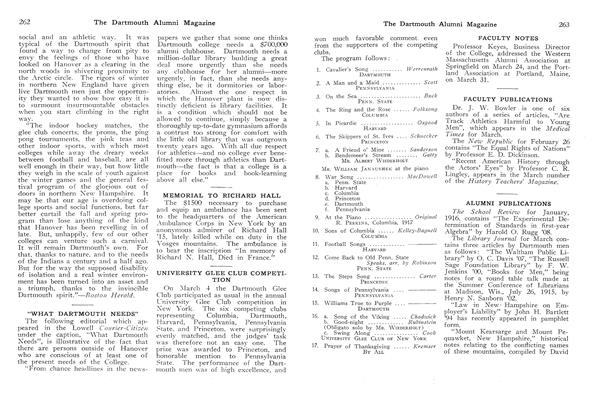

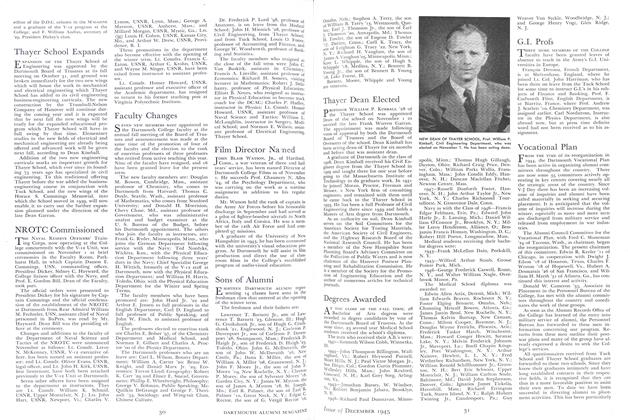

FINAL REPORT OF THE ALUMNI FUND—FOR THE YEAR ENDING JUNE 30, 1930

No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1112 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64

Class 1879 1868 1872 1881 1873 1900 1874 1867 1887 1911 1898 1884 1871 1913 1919 1889 1885 1892 1897 1910 1896 1915 1866 1878 1880 1886 1901 1902 1903 1905 1907 1916 1920 1894 1908 1912 1923 1924 1870 1914 1921 1922 1926 1876 1909 1890 1917 1899 1875 1927 1904 1928 1891 1877 1895 1925 1918 1888 1883 1882 1893 1906 1929 1869 1861 1863 1864 1865 Medical School Tuck School Honorary Miscellaneous

Living Graduates 20 3 19 32 22 92 19 1 47 221 61 37 14 203 214 39 32 42 78 235 41 256 7 28 22 38 104 120 118 129 178 240 222 75 168 213 409 363 5 244 255 243 403 23 189 47 252 91 19 364 118 414 44 20 55 382 258 43 37 31 55 152 466 7 8,379

Contributors 28 4 14 15 23 89 15 2 45 164 61 33 16 200 154 23 18 46 53 163 29 187 5 19 16 24 89 91 82 95 86 150 197 64 102 160 257 234 7 164 179 130 238 11 95 30 118 58 6 204 88 233 21 9 25 179 138 20 14 20 32 74 201 1 1 4 1 55 4 3 1 5,417

% of Contributors 140 133 74 47 105 97 79 200 96 74 100 89 114 99 72 59 56 110 68 69 71 73 71 68 73 63 86 76 69 74 48 63 89 85 61 75 63 64 140 67 70 53 59 48 50 64 47 64 32 56 75 56 48 45 45 47 53 47 38 65 58 49 43 65%

Quota $359.00 34.00 224.00 684.00 247.00 2,920.00 247.00 11.00 1,452.00 4,461.00 1,945.00 975.00 168.00 3,660.00 2,701.00 1,222.00 925.00 1,351.00 2,477.00 5,005.00 1,317.00 4,091.00 78.00 504.00 454.00 1,166.00 3,296.00 3,632.00 3,441.00 3,470.00 4,416.00 3,632.00 2,612.00 2,388.00 3,957.00 4,058.00 3,772.00 3,043.00 67.00 4,103.00 2,786.00 2,449.00 2,942.00 308.00 4,237.00 1,474.00 3,587.00 2,858.00 224.00 2,449.00 3,307.00 2,539.00 1,412.00 336.00 1,760.00 2,987.00 3,470.00 1,379.00 964.00 712.00 1,760.00 3,895.00 2,522.00 78.00 $135,000.00

Contributions $4,207.00 125.00 580.00 1,540.00 451.00 5,300.00 391.00 16.00 1,869.25 5,518.50 2,249.00 1,126.00 187.00 4,026.64 2,970.00 1,320.00 991.65 1,372.00 2,526.00 5.107.70 1,333.35 4,131.00 78.00 504.00 455.01 1,166.00 3,296.00 3,642.00 3,450.00 3,470.00 4,416.00 3,645.00 2,532.00 2,240.00 3,250.00 3,255.50 2.905.71 2,326.00 50.00 3,084.50 1,919.75 1,700.46 2,028.66 208.00 2,835.00 959.00 2,150.00 1,683.00 130.00 1,426.50 1,895.00 1,436.00 794.00 185.00 950.00 1,625.85 1,768.00 695.00 439.00 318.00 791.00 1,738.00 1,039.81 5.00 15.00 45.00 25.00 525.00 35.00 545.00 116.85* $121,130.69

% of Quota 1172 368 259 225 183 182 158 145 129 124 116 115 111 110 110 108 107 102 102 102 101 101 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 97 94 82 80 77 76 75 75 69 69 69 68 67 65 60 59 58 58 57 57 56 55 54 54 51 50 46 45 45 45 41 90%

Includes income from sale of Dartmouth College Maps. (Classes are arranged according to percentage of quota.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMy Love for Languages

August 1930 By Dr. James A.Spalding '66 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

August 1930 By Frederick W. Andres -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

August 1930 -

Article

ArticleMidsummer Musings

August 1930 By Phil Sherman -

Article

ArticleAgain Among the Hills

August 1930 By Arthur Dewing -

Article

ArticlePhysical Oversight of the Undergraduate

August 1930 By Dr. John W. Bowler