A LTHOUGH the subject matter is twenty-five years old, this article most emphatically is not remiA. JL niscent. The alumnus several years on the near side of fifty still is certain that he should elect, desperately perhaps, the life's objective courses instead of the seminars on the writing of memoirs. The courses to be discussed are those of the early nineteen hundreds but their application is present so that the discussion may justify itself as something for the reading of the immediate instead of a forgotten generation. Furthermore, when the hope is expressed that the curriculum may still offer the same or similar courses, the future is likewise given proper consi deration.

Dartmouth's contributions to the continued and succeeding generations of Dartmouth men must be, primarily, in the background of men and books, friendships and activities, ideas and principles, that come from somewhere and everywhere around Hanover. Let us call it culture, for that surely is sufficiently general. When, therefore, an undergraduate course becomes so immediately helpful that an alumnus of a quarter of a century finds himself, consciously or unconsciously, almost daily applying its principles, the practical as well as the cultural must be served. One who feels a sincere appreciation for the benefits from a course of twenty-five years ago cannot refrain from the wish that the curriculum may not have been so assiduously modernized as to send these courses into the discard. The articles in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE on the present courses at Dartmouth and especially that on the courses in English recalled to at least one alumnus a certain course in English whose practical instruction has been applied almost daily since graduation, and to which, therefore, he feels deeply indebted. He is hereby obeying the urge to give expression to this appreciation.

In old Culver, Craven Laycock presided. The days of speaking in the grand manner were passing, although an occasionally koo-kah-koo specialist orated in vigorous and rounded periods. Upon such who shouted merely loudly and noisily the Laycock scorn fell in withering fashion. The course was for those who sought the simple but essential principles for the presentation of ideas in clear, definite, and convincing English. The catalogue classified it as English 3 and 4. The course was known as Argumentation and Debate. In truth, however, it was a course to free the student mind of cob-webs, to clear student ideas of their muddled uncertainty, to make the student English concise and definite, and to strip the student public speaking and writing of its bombast. It did this by precept, but it did this even more effectually by student effort, and by preceptorial comment of a kind that was never forgot. Culver is down and years have passed, but there is a generation of Dartmouth men that associates Craven Laycock with a course in clear thinking and accurate expression and that gives credit to him today for teaching practical principles of effective public expression. Few of that generation—may we be thankful therefor—are orators. However, a man who heard and learned and was criticized and perhaps lampooned in those days is not bewildered today when he is called upon to make a public presentation of a current subject either in speech or in print. He is convinced that he must know his subject thoroughly, that he must analyze his matter logically, that he must think accurately, and that he must speak or write clearly, or have his efforts suffer from the public the same scorn that beat down upon him from the desk in Culver.

If the men of the Laycock Argumentation Period of Dartmouth Civilization do not write or speak accurately or clearly it is not Craven Laycock's fault!

If the men of the Laycock Argumentation Period of Dartmouth Civilization do think, write, and speak accurately and effectively, let them not vainly take all of the credit unto themselves! The mid-forties make a man's thinking hopelessly out of date. The man of such maturity scarcely dares express himself on the essentials of education. Though there is peril in the venture, one of that generation offers a formula that would still satisfy him that a youth of today who would benefit from all that it offers would have the essentials upon which education is established. A youth who could hear John K. Lord read the odes of Horace, who could listen to Clothes-Pins Richardson reveal the beauties of English literature, who could have the wonders of the physical laws made plain in the experiments of Ernest Fox Nichols, who could experience the awakening of thought in philosophy under the guidance of Dr. Herman Harrell Home, who could learn thoroughly the fundamental principles of economics and remember them as taught by George Ray Wicker, who would absorb from Craven Laycock the truth that he who knows but knows not how to tell what he knows is still lost in ignorance, and who might be touched by the personality and feel the thrill of the vesper hour preaching of Dr. Willam Jewett Tuckerthat youth, I challenge any one, would have upon his mind and character the marks of an educated man!

This article is not reminiscent. The Dartmouth of today, assuredly may not have the same, but it must have that which is just as good.

What Course in DartmouthPleased You Most? In the past two years the ALUMNI MAGAZINE has asked members of the faculty to present material dealing with their departments and courses. Now, the MAGAZINE turns to the alumni and asks former students to describe courses which had the most vital effects upon them. One such article is here presented. The editors hope that alumni will answer this request, but reserve the right to select those letters for publication which cover as a whole the greatest number of fields. For example, —if letters duplicating experiences in one single course are sent in, only one letter from such a set will be published. However, as this series is experimental, the editors are anxious to have as many letters as possible. Mr. Eichenauer is the first contributor to the series.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe College as a Cooperative Enterprise

October 1931 By Ernest Martub Hopkins -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Outing Club of Boston

October 1931 By Hans Paschen, Tuck School '28 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

October 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1910

October 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1930

October 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1911

October 1931 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh

Article

-

Article

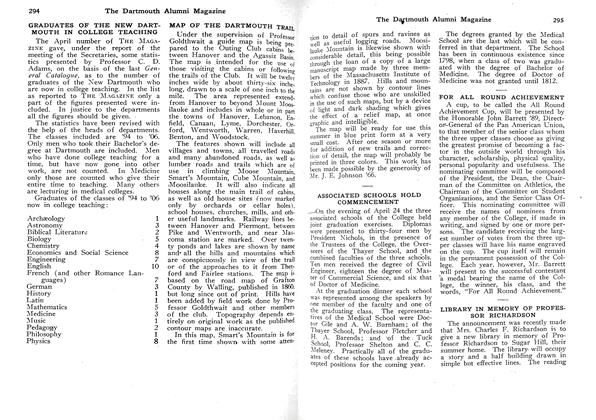

ArticleGRADUATES OF THE NEW DARTMOUTH IN COLLEGE TEACHING

June, 1914 -

Article

ArticleNewcomers Among Our Contributors

JUNE 1930 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

April 1934 -

Article

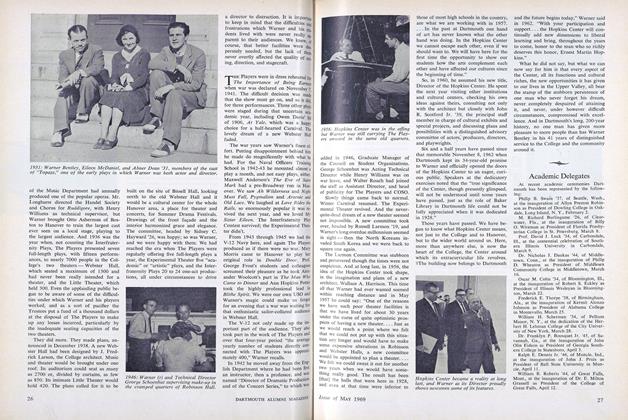

ArticleAcademic Delegates

MAY 1969 -

Article

ArticleCONSTRUCTIVE TENDENCY NOTED

March 1938 By Ben Ames Williams Jr. '38 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

February 1952 By William P. Kimball '29