For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

COLLEGE ENROLMENT GROWING

DESPITE the hard times, the enrolment of students in the colleges and universities for 1930-31 appears to have increased slightly over the figures of the year before. Dean Walters of Swarthmore has recently filed an exhaustive report, which reveals the enrolment of full-time students in recognized colleges and universities to be 31/4 per cent greater than in the previous year. What are called "grand totals," covering part-time students and summer schools, reveal only a 1 per cent increase—but even that is not a loss. About half the colleges that have 500 students or less report an increase this year, and 71 per cent of the institutions which boast 3000 or more show a similar increment. The exception appears to be only in the case of some women's colleges and coeducational institutions, in which there has been a decline in the registration of women and girls. It would seem to indicate that the country feels it can worry along, even if not so many of the young women go to college, but that the importance of higher education for young men suffices to keep the figures of total enrolment steadily mounting in spite of everything.

Positive figures may be interesting. The University of California (Berkeley and Los Angeles) leads the field with a total full-time registration of 17,322; Columbia comes next with 14,956; Harvard is ninth in the list, and Yale 20th. Taking in the part-time element, Columbia jumps to the front with 23,144—and California falls to fourth place, with two other New York institutions (New York University and the College of the City of New York) coming in between. It is a startling revelation of the facilities which the American metropolis offers for part-time work and of the degree to which they are availed of. Among the women's colleges, Hunter—which is. part of the New York City public school system—stands first with 4614 students, and Smith stands next with 1986.

Dean Walters regards the figures as showing that there is in the American public an abiding faith in the usefulness of the higher education and suspects further that present economic conditions have something to do with it—because it is difficult just now for young people to find jobs, and the families that have savings sufficient to make it feasible conclude that their young might as well be in college as out of work. This may be open to question. It is possible, rather than probable, that families which would otherwise be less likely to send children on to college will do so when times are hard, college expenses being notoriously heavy in these days of high tuition fees, and chances for self-help notoriously lessened in times of economic depression. However, that is all speculative. The certainty is that despite the depression the total full-time enrolment is per cent higher than last year, and the total including part-time and summer schools is 1 per cent higher.

EMOTIONAL REACTION?

IMPULSIVE youth seems to have looked upon the recent episode involving the conflict between Judge Lindsey and Bishop Manning as in some sort a denial of the sacred right of free speech—hence the filing of sundry undergraduate protests favoring the judge as against the bishop. It is rather hard to see how any abridgment of free speech has been attempted, however. No one has prevented Judge Lindsey from preaching his crusade for a new theory of matrimony—not even Bishop Manning. The latter, indeed, intimated that it was inadvisable to listen; but that is a different thing from trying to muzzle the judge. Is there not a corresponding right of freedom to close the ears, as well as a god-given privilege to all and sundry to be free to open the mouth?

Whether or not the colleges get much wholesome publicity from the eager youth who so chivalrously espouse the cause of those whom they esteem to be downtrodden and oppressed by arbitrary authority, is possibly a matter of taste. Some will feel that an overstressed football team does rather more good in the long run than all the shrill protests that arise from the indignant undergraduate societies of the land—but thiwill be denied with appropriate scorn by such as regard with favor the propensity to let the heart rule the head. It remains a bit of a puzzle wherein Judge Lindsey's right of free speech has been interfered with, merely because a palpably over-hasty bishop has said that he felt people ought not to listen, or because somebody prevented the angry social reformer from making immediate reply from a press table in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. The whole business was what Mr. Kipling might call "an unsavoury interlude" at besta nd hardly a thing for crusading students to make an issue of. There was very little credit for anybody in the episode.

THE NATION'S PROBLEM

A FEW days before Christmas the President of Dartmouth College made public, by request, a letter which he had written in response to an invitation to attend a conclave of religious and civic leaders, to consider afresh the undying topic of prohibition by constitutional amendment. It was a perfectly frank and courageous letter, the contents of which need not be dwelt on here because by this time it is probable that every interested reader in the United States knows what was said. The import of it all was that the great experiment, admittedly made with the noblest motives, of prohibition by constitutional amendment seemed to Dr. Hopkins after more than ten years of -trial to be productive of infinitely more deteriments than benefits.

Naturally opinions differ on this matter; and one of the difficulties is always to see that disputants keep their tempers sufficiently to enable a calm and logical argument. The President's letter seems to the present writer by far the most self-contained and broadminded presentation of the case against the experiment that has yet come from any man of similar high standing. There is nothing in it to infuriate a sincere devotee of the Eighteenth Amendment—save as any criticism thereof always does infuriate its more extreme advocates. The unfortunate propensity of the latter is to assume that any one, who does not go the whole distance of demanding that this law shall be enforced whether anything like a majority of the people want it or not, must necessarily be a defender of alcoholic abuses—as if the Amendment were a divinely inspired commandment and constituted the sole bulwark of the country against the evils of intemperance. It is well, therefore, to have opinions from men with the respect and esteem of the public at large, whose earnest desire for the minimizing of the drink evil is unquestioned, laid before the people of the United States—men of high character and unquestioned probity, of whom it cannot be said that their opinions flow from unworthy personal desires.

Now and then a commentator has objected that President Hopkins appears to suggest no detailed alternative plan, as if it were impossible to feel that the Eighteenth Amendment was a failure unless one had some pet panacea of one's own to substitute for it. It does not appear that this necessarily follows—but a hint of the President's beliefs lies, no doubt, in his statement that this is a state, rather than a federal, function.

CERTAIN MAJOR NEEDS

PERFECTION is finality—and finality is death. It might be a very unhealthful sign if Dartmouth College stood in need of nothing more to increase its efficient service. Of that there is no danger, of course. Great as has been our expansion in material plant, there remain numerous things to and least one of them of such arresting magnitude as to warrant the belief that it will have to await the passage of many years for its accomplishment. Still—you never can tell.

This major project, as occasionally sketched by the Administration, relates to the creation at the south side of the Campus of a social centre to balance the intellectual centre now in full flower on the north. In its larger concepts, this envisages the removal of the hotel from its immemorial site and the creation of a group of buildings, extending from corner to corner, to house the manifold social activities of the students, to provide a really adequate auditorium, eating facilities, a graduate club, and so forth. The great cost of such a plan probably makes it dependent on the discovery of some unusually generous donor or a group of donors who will, individually, make provision for various units of the group.

An addition is urgently needed to Wilder Hall, the headquarters of the Physics faculty, which it is estimated would cost in the vicinity of $400,000.

It would also be welcome to append to the gymnasium plant a unit for the accommodation of squash and handball courts, in these days when stress is laid on the necessity for regular and stimulating physical exercise for growing young men. We have thus far no facilities at all for squash-racquets—a sport everywhere recognized as uncommonly useful for bodily developmentand the handball court admits of great expansion over what now is possible. The locker space and shower baths are of insufficient size and are not properly ventilated. Hopefully this plan, long agitated by the un- dergraduate publications, will be taken up seriously by the Athletic Council and steps planned for its realization.

Aside from the College plant proper, there is always the opportunity to increase the endowment for Dick's House, funds for which have already been subscribed in part by various donors to enable an income to defray expenses for students unable to bear the cost of treatment at this magnificent infirmary—to give it a name which seems to be about the only one available, although not exactly descriptive because of its homelike nature. Gifts to this purpose may be of any size, and the opportunity has already been availed of by several givers to make their contributions take the form of memorials.

PRESIDENTIAL PILGRIMAGES

Now come the winter days when there devolves upon the President of the College one of the most arduous of his annual tasks, and at the same time one of the most valuable to the interests of Dartmouth—to wit, the duty of making a pilgrimage through the country to meet various organizations of alumni scattered across the map of the United States. These trips, frequently extending from coast to coast and from Lakes to Gulf, vary in comprehensiveness with circumstances of health and opportunity; but in any case they are thousands of miles long and lay upon the President a burden of work, as well as open to him an avenue of pleasure. One must journey far and make many speeches. To the individual alumnus, who attends a single dinner and hears the President speak, it usually seems like an isolated performance; but it is in realityonly a single item in a long series of similar dinners in cities scattered from Boston to Chicago and possibly to San Francisco, each with its eager group to be met, and above all talked to. That it is a pleasure to the President, as well as to his auditors, is undoubted—but his is the really hard work.

The object in mentioning it here is to emphasize the arduous side of such an undertaking and to make it plainer than it might otherwise be why a college official facing such a pilgrimage program may have to cut it far shorter than he himself would wish, and of course infinitely shorter than multitudes of alumni had hoped for, in response to the dictates of sheer physical fatigue. Listening to President Hopkins as he talks about the College is one of the greatest delights, as we all know; but pray, when thinking of your own alumni dinner, reflect that it is but one of a hundred just like it the country over, from the viewpoint of one whose desire is to attend them all and to bring with him the latest from Hanover. No man can possibly have both the time and the energy to make such a journey all-inclusive —even a man so vigorous and so manifestly in the prime of life as President Hopkins. After all, it is but one part of his job, and the more immediate tasks of administration cannot be neglected in favor of this other activity, vastly important as it is.

The importance is unquestioned. It isn't merely that to hear the head of the College discourse about it and its projects is always of absorbing interest. It is also that such presidential visits enhance the morale of Dartmouth alumni and intensify that loyalty which is the chief of our imponderable assets. Just how comprehensive the itinerary will be this winter is at the moment of writing undetermined—but it is safe to say it will be made as inclusive as considerations of health and the pressure of other duties will allow.

CABINS AND TRAILS

WINTER reigns in Hanover. This is the month of Carnival. The Outing Club and the many outdoor sports and activities associated with its name hold the center of the undergraduate stage. Mid-winter offers an opportune occasion to make recognition of the value of the D. O. C. to the College. Senior classes traditionally vote to award the distinction of "the organization which has done the most for Dartmouth College" to the Outing Club. To graduating seniors, and to all Dartmouth men, it most nearly symbolizes what they want to have typify student life.

To those a part of the Hanover scene the Outing Club appears, by all odds, as the most important extracurricular activity. Through the years since snow was first "discovered" on Hanover Plain the Club has steadily progressed and developed in its growth. Expectations of the highest sort in regard to any program sponsored by the Outing Club are not disappointed. The thousand and one details to be attended to in planning and running the Winter Carnival are all absorbed by this astonishing organization. Individual duties and assignments are taken care of as though apprenticeships of several years had prepared all concerned. Executives who are seniors or juniors in college direct the work of scores of assistants. It all goes smoothly. Always, it seems,the standard of the Outing Club is raised a little higher.

Even snow, that much-desired commodity at Carnival time, is somehow secured. If the eve of festivities is reached and no snow has yet appeared, a student body arising on the day when guests will be met will note the heavy fall of snow during the night and evidence gratification, but little surprise. This accomplishment of the Outing Club is in line with past demonstrations of providing well and fully.

Significant as the D.O.C.'s function at Carnival may be, it is only one figure of the pattern which is woven from all its activities to make the whole picture of a year's work. The building of health, the moulding of character, the development of individual initiative and resourcefulness, executive training, an appreciation of the beauty of Nature—these are the things which days on trails and nights at cabins foster. Boys now preparing for Dartmouth are dreaming of evenings around a fire in a distant mountain cabin, snug and warm from howling winds and drifted snow, surrounded by friends, singing all the good old songs. Then they will swear sacredly to themselves that "This is the best crowd of fellows I've ever been with and the best time I've ever had in my life." Perhaps their fathers have told them of these fires and of that fellowship. Their dreams may be founded on a feeling that Dartmouth can be like that. They won't be disappointed. It is all true.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWhy and What—the Outing Club

February 1931 By Craig Thorn, Jr. '31 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

February 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPresident Hopkins on Prohibition

February 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

February 1931 By Truman T. Metzel -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

February 1931 By "Hap" Hinman -

Books

BooksA SON'S PORTRAIT OF FRANCIS E. CLARK

February 1931 By Charles D. Adams

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorREGARDING CLASS FUNDS

December, 1925 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

January, 1926 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

NOVEMBER 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

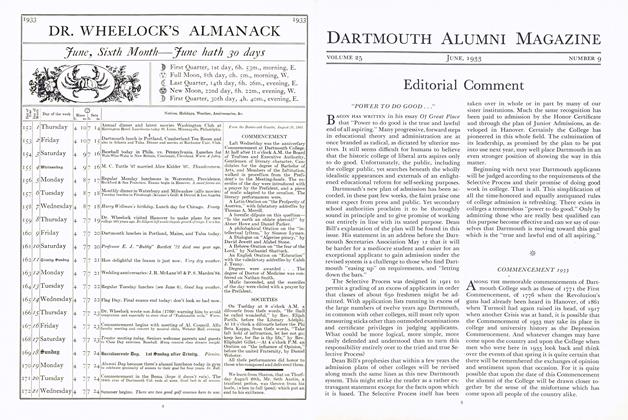

Lettter from the EditorCOMMENCEMENT 1933

June 1933 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorDouble Vision

MARCH • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor"Only Connect..."

MAY 1986 By Douglas Greenwood