The Moscow Art

CAMPED up here in the Polish city of Wilno on the railroad line which comes from the junction at Bialystock, the junction where one train goes on to Moscow and the other proceeds by Wilno to Leningrad, I see by the posters that the Group Stanislawsky is opening for a short run. The word Stanislawsky is magic. There is only one Stanislawsky, the director of the theatrical players who have the world as their admirers. And to think of that company coming here! For this is the city that has suffered the most in the world from Tsarist misrule. Here the Russians forbade the Polish language, here they closed the university and Polish schools, here they attempted to cover everything with a gloss of Tsarist polish, and how futilely.

It is now ten years since the Bolshevik army took this city and plastered it with bullets, tore down buildings, and suppressed Polish nationality. It has come to Poland again, and the university and schools are reopened, Polish is spoken in the streets, and there is no attempt to suppress the White Russians, or other races living here. And to top it all, a Russian company is coming here to give a play! It took temerity; it took courage; I don't know whose idea it was, but it was a splendid experiment.

For on the first night—it was Ostrovski's old melodrama, Biednost nie Porok, Poverty is No Crime—the applause in that Polish theater shook the roof. And when, at the close of the play, Monsieur Pavlov stepped forward as Stanislawsky's representative to greet the crowd, the company was literally snowed under with flowers. Baskets and baskets of them, set pieces, bouq uets, loose flowers and long-stemmed blossoms tied with white ribbons. For in art there is no such thing as war. The artist of one Slav country greets another, and audiences are quick to appreciate. I don't know how Polish companies would be received in Russia, but there is a something in the Russian heart that is quick to app reciate personal spirituality. Even the firing squad ordered out to execute poor Admiral Kolchak in Siberia these ten years ago fired over the admiral's head because he stood easily and proudly and faced them with a smile after having borrowed a cigarette from one of the firing squad. And even when the officer in command was obliged to shoot him himself, the soldiers of the red army never afterward allowed an insult aimed at Kolc hak to pass unchallenged.

THE THEATRE WILL LIVE

But even now, despite the fact that the Soviet Government has used the theater as a ground for propaganda, the magnificent figure of Stanislawsky stands out head and shoulders above his newer competitors in the field of art. The Moscow Art group lives up to its name; it perpetuates all the old classics of the Russian stage and allows no interference with lines. It has come to the point now where the Russian dramatic masterp ieces are played in translation all over the world and the traditions of the Moscow Art theater have gotten into every little and experimental theater in the world. The moving picture machine is a terrific competitor of the stage in these days, but the machine will never crowd out human personality and art. The world through a piece of glass, or the sound of the world through a wax or rubber record, broadcasted through a tin horn, will never down the artistic tradition of the theater. The little theater has become the revolutionist in a world of moving pictures, and it will win out just as the amateur actors of the Elizabethan days won out in a world of bear-baiting and blood-letting. It is quite curious to note that the Dartmouth Players organization in the past few years has turned out a number of real actors who have stepped directly from the boards of Webster Hall to the stages of large and important theaters in New York and even London. The Little Theater is still holding the fort when the rest of theatrical enterprise seems to be running to machine-made film.

This Moscow Art group was in tour. It was carrying out in foreign countries the ideas of the art theater directors and the enthusiasm of Anton Chekov, who was as great a saint to the Russian theater as O'Neil is to ours. Elaborate effects in scenery were lacking. Had Edwin Booth lived in our day and thrown in his lot with one of the little theater groups he would have felt quite at home with the movement. His idea was always that personality is the greatest stage effect. And even Burbage played with a sign indicating a scene. So when the Moscow Art theater suggests a cellar with a curving irregular roof, or night by a black screen, or a cherry orchard by one or two blossom-laden boughs, the scenery never dominates the human interest. I have seen one curiously set flower in the middle of the stage, with an electric light below it, suggest at once the fact that the scene is in the country and that the time of year is summer.

THREE GREAT PLAYS

Of the whole repertory of the Moscow Art theater I like best Poverty is No Crime, the Cherry Orchard of Chekov, and the Lower Depths (Na dnie) of Gorky (Pieshkov). The Tolstoy plays, the Living Corpse and the Power of Darkness, although tremendous for philosophical teaching and sheer dramatic power, do not seem to me the equal of these other plays in absolute stage effect. Both the Living Corpse and the Power ofDarkness impress the observer at the very beginning with the same dark influence that he feels at the end. He knows just what the effect is to be the minute the curtain is up. It's a kind of static tragedy. But the three other plays instead of following a level, rise gradually to a high place and then snap the tension with a climax. Note that in the Cherry Orchard there is a broken violin string in the distance at two critical places in the play. I think that the Greek critic might like the Tolstoy plays which begin with "Woe-Woe-Woe" and end with "Woe-Woe-Woe," all in the same note.

In Poverty is No Crime, the merchant Tortzov is a truly fit character for tragedy—a merchant of the proud old school. Professor Clarence A. Manning of Columbia says of him, "He realizes his power perfectly, and compared to him Babbitt is a cultured gentleman of the highest rank." He is about to marry his daughter-to the most repellant, most loathsome, most hideous neighbor, who happens to be wealthy; he drives from his home a brother who happens to be poor; he makes life miserable for everybody and drives all his relatives constantly to religion as the only peace on earth. The whole play has a very tragic effect. And yet at the last moment when the poverty-stricken brother makes his desperate plea and shows up the wealthy lover as an actual scoundrel, then the proud merchant forgives his brother and breaks off the marriage which would have been terrible. And in his rage he decides to throw his daughter at the cheapest clerk on the place. ..Oh ye gods—the daughter had long been in love with that very clerk! One is ready for tragedy, when suddenly the skies break, and in the Words of Mr. Boffin, "Up we go."

STAGE CRAFT IS SUPERB

The stagecraft of this play is wonderful. People keep doing the most surprising things. When the room is in darkness a servant enters and lights from a candle a hanging string. Presto, the room is lighted, for the string is soaked in oil and flashes up to a chandelier, much to the surprise and delight of the audience who had never seen such a thing before. The way the flame travels leisurely from candle to candle is a good part of the play. And then the Christmas mumming, and the folk songs and the masquerading, it's all part of the show. As in the one-act play of Chekov, the MarriageProposal, the suitor faints, and is restored by being sprinkled with water—the sprinkler, Pavlov, fills his mouth with water at a nearby tank and shoots the water high into the air over the fainting man. It must have taken hours of practice to attain the fountainlike perfection of that trick. Likewise in the Living Corpse, when the seduction of an intellectual man is shown, the players spend half an hour or more in the gypsy house to actually put on the stage the method of intellectual seduction; the music of guitars, singing, reciting. When the Moscow Art people are staging a play one is constantly caught by little surprises just like this. And as to lines, well, lines are simply taken for granted; anyone can learn lines. It's the action that counts. Note the long soliloquies, or perhaps one-man speeches in Chekov which make his plays rather dull reading; well, on the stage the words accompany continual action. I can see very well how any but a most astute stage manager would turn down Chekov's plays in manuscript (as actually happened). It takes a theater company of just the Moscow Art's ability to create good plays. An example is that little Chekov play The Doctor, in which two actors simply enact a patient with a bad tooth and a surgeon-dentist who tries to take out the tooth. There is an half hour of the most exquisite dramatic sensation in it, in which one goes through agonized torture, humor, pity, fear, and exaltation.

The Cherry Orchard and the Lower Depths are too well known for much comment, but one feels that the highest crisis of dramatic feeling is reached at the point in the former where the prosperous son of a former serf announces in the midst of a gay evening party that he has purchased the estate and its orchard, the orchard being of course symbolic of the best qualities of the old aristocratic class, now hopelessly out of date in a new world. In this play it is again the opportunity afforded the actors that makes the play great, and of course the opportunity is in itself a product of Chekov's imagination. To read the Cherry Orchard brings but little emotional response. I know of no greater dramatic climax than that of the Cherry Orchard, and the note on which the play creeps out at the end,—the old forgotten servant who is left behind and dies,—the sound of chopping in the cherry orchard, and the broken violin string in the distance announcing again that another earth-melody has come to an end. It is written by a man who visualized his theater as he wrote. The playwright must have these possibilities for action in his head before he puts mere words down on paper.

As to the Lower Depths, which has been called "low," "morbid," "disgusting" and many other names of the sort, there is a much greater word value in it than in the Cherry Orchard, for it reads interestingly, possibly because of the natural tone of the conversation. The intense religious feeling behind it, embodied in the pilgrim Lukas, easily communicates itself, but again it is a play that acts marvelously. And a theater such as the Moscow Art seizes upon the possibility of the symbol, when the woman dies in her bed one sees merely a stiffened hand thrust through the coverlet, or one sees a shadow traveling across the stage and alighting on the bed. One sees Lukas looking for a shrine before which to cross himself and finally using a crosspiece of beam near the stove. The play is literally filled with such touches, and the writer must have had them in mind, but it took a company like the Moscow Art to raise this play out of its sordid self and give it the interpretation that Gorki put into it. The Lower Depths is the most magnificent play of the lot, I think; magnificent in that it creates an emotional response in the observer which seems to justify the word. One feels that humanity in its very lowest phases possesses some glint of absolute glory,—that even the reflection of a remembered good thought lives like a distant sun in the hearts of men. With the proper influences great and noble qualities bloom in the most degraded heart,—even if the realization is one of hopelessness,—the actor fallen from his former estate realizes that he is hopeless, and hangs himself rather than eke out the miserable existence of sponging on friends and enemies. Hardly moral, —yet extremely so.

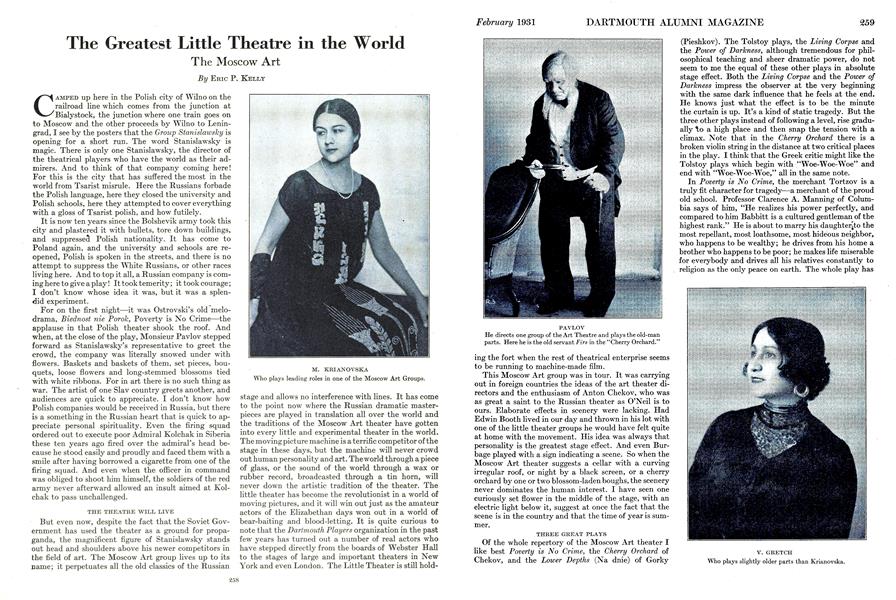

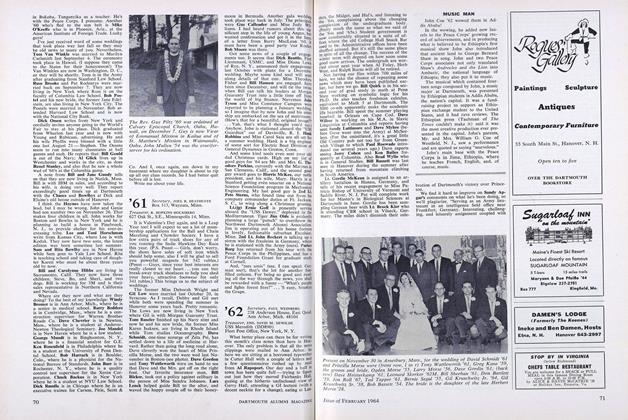

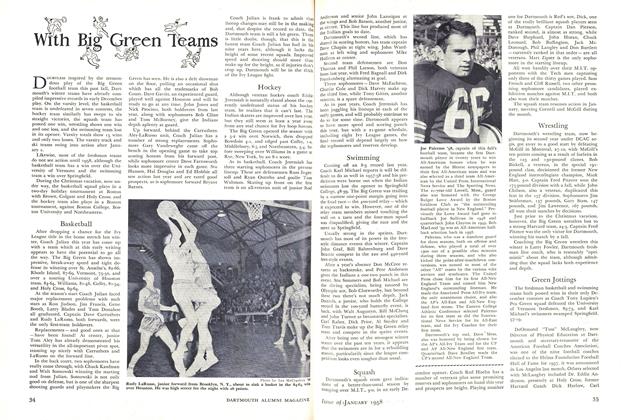

M. KRIANOVSKA Who plays leading roles in one of the Moscow Art Groups,

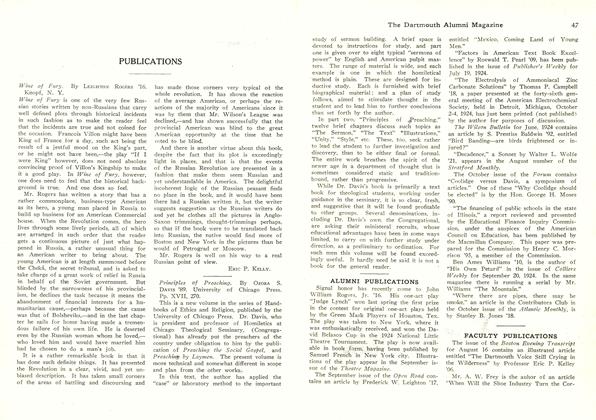

PAVLOV He directs one group of the Art Theatre and plays the old-man parts. Here he is the old servant Firs in the "Cherry Orchard."

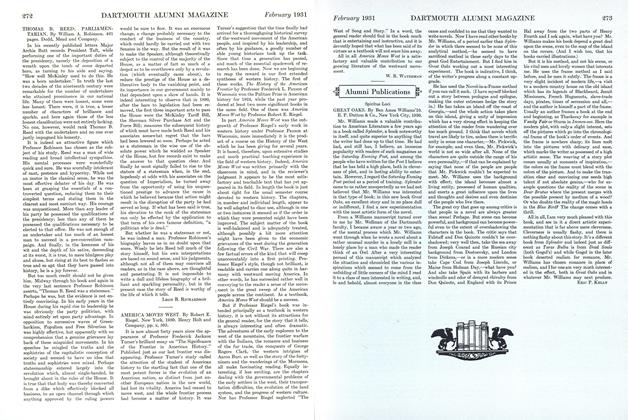

V. GRETCH Who plays slightly older parts than Krianovska,

TORTZOV As the merchant by the same name in Ostrovsky's "Poverty is No Crime."

VYROTJBOV As Gaeff in the "Cherry Orchard."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWhy and What—the Outing Club

February 1931 By Craig Thorn, Jr. '31 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

February 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPresident Hopkins on Prohibition

February 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

February 1931 By Truman T. Metzel -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

February 1931 By "Hap" Hinman

Eric P. Kelly

Article

-

Article

ArticleOFFICERS IN CHARGE OF THE MILITARY WORK AT DARTMOUTH

November 1918 -

Article

ArticleMUSIC MAN

FEBRUARY 1964 -

Article

ArticleBACK TO NORMALCY

January, 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleWrestling

January 1958 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleMagic Touch

NovembeR | decembeR By Gavin Huang ’14 -

Article

ArticleCROSS COUNTRY

DECEMBER 1970 By JACK DEGANGE