By LEIGHTON ROGERS '16. Knopf, N. Y.

Wine of Fury is one of the very few Russian stories written by non-Russians that carry well defined plots through historical incidents in such fashion as to make the reader feel that the incidents are true and not coined for the occasion. Francois Villon might have been King of France for a day, such act being the result of a jestful mood on the King's part, or he might not have been,—the play "If I were King" however, does- not need absolute convincing proof of Villon's Kingship to make it a good play. In Wine of Fury, however, one does need to feel that the historical background is true. And one does so- feel.

Mr. Rogers has written a story that has a rather commonplace, business-type American as its hero, a young man placed in Russia to build up business for an American Commercial house. When the Revolution comes, the hero lives through some lively periods, all of which are arranged in such order that the reader gets a continuous picture of just what happened in Russia, a rather unusual thing for an American writer to bring about. The young American is at length summoned before the Cheka, the secret tribunal, and is asked to take charge of a great work of relief in Russia in behalf of the Soviet government. But blinded by the narrowness of his provincialism, he declines the task because it means the abandonment of financial interests for a humanitarian cause,—perhaps because the cause was that of Bolsheviks,—and in the last chapter he sails for home having made a tremendous failure of his own life. He is deserted even by the Russiah woman whom he loved,— who loved him and would have married him had he chosen to do a man's job.

It is a rather remarkable book in that it has done such definite things. It has presented the Revolution in a clear, vivid, and yet unbiased description. It has taken small corners of the areas of battling and discoursing and has made those corners very typical of the whole revolution. It has shown the reaction of the average American, or perhaps the reactions of the majority of Americans since it was by them that Mr. Wilson's League was declined,—and has shown successfully that the provincial American was blind to the great American opportunity at the time that he voted to be blind.

And there is another virtue about this book, despite the fact that its plot is exceedingly light in places, and that is that the events of the Russian Revolution are presented in a fashion that make them seem Russian and yet understandable in America. The delightful incoherent logic of the Russian peasant finds no place in the book, and it would have been there had a Russian written it, but the writer suggests suggestion as the Russian writers do and yet he clothes all the pictures in AngloSaxon trimmings, thought-trimmings perhaps, so that if the book were to be translated back into Russian, the native would find more of Boston and New York in the pictures than he would of Petrograd or Moscow.

Mr. Rogers is well on his way to a real Russian point of view.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSOME ATTRIBUTES OF UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION

November 1924 By President Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

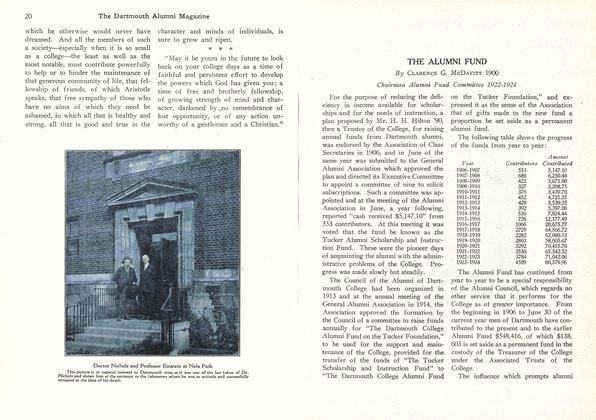

ArticleTHE ALUMNI FUND

November 1924 By Clarence G. McDavitt 1900 -

Article

ArticleHaving but recently welcomed to the ranks

November 1924 -

Sports

SportsATHLETICS

November 1924 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1924 -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1928

November 1924 By E. Gordon Bill

Eric P. Kelly

Books

-

Books

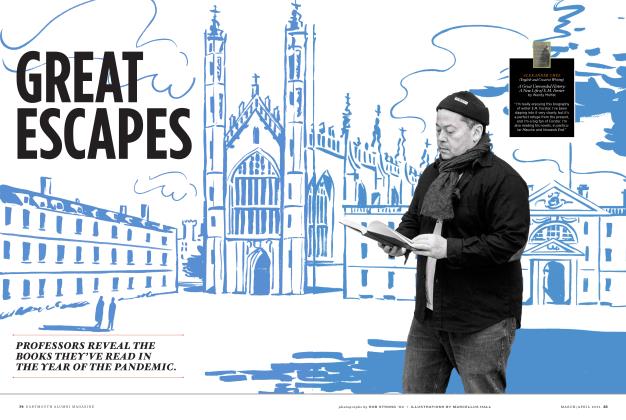

BooksGreat Escapes

MARCH | APRIL 2021 -

Books

BooksROBERT FULTON AND THE STEAMBOAT BOAT

February 1955 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Books

BooksOCEANS, POLES, AND AIRMEN.

JUNE 1971 By DESMOND E. CANAVAN -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

April, 1923 By F. E. BROWN. -

Books

BooksSPINDRIFT

November 1951 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksAN ASTRONOMER'S LIFE

December 1933 By L. B. R.