For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

COUNCIL ELECTIONS

THE MONTHS of April and May bring with them the distinctly important duty of providing regional alumni councillors, by choice among the alumni living in the various districts. It happens that in most of these districts the present councillor is eligible for another term; but in those where this is not the case, as in the membership falling vacant for the New England states, a spirited contest is probable and in fact is to be welcomed as indicative of appreciation of the value of such a position to the service of the College.

It has been said many times in the past and should be said with equal frequency and force in the future that the choice of a councillor to represent any district should depend on a variety of considerations, including the probability that the candidate favored will take his duties seriously and will attend the meetings of the Council, as well as his general fitness as an alumnus of good judgment and loyalty to Dartmouth. A councillor of exceptional ability who seldom or never attended the sessions of the Council would exert little or no influence on such matters as fall within the province of this representative body. Two meetings are held every year—one invariably at Hanover at the start of Commencement program, and the other at any convenient point away from Hanover in the fall. The latter meeting has in recent years been held variously at Chicago, New York and Boston, usually at the time when some strong incentive, like a big football game ar the midwestern Pow Wow, existed to insure a general gathering of alumni. The aim is to lighten the burden, when possible, for councillors living in the remoter districts by shortening the journey; for it is no small tax both in time and in money for a delegate hailing from the Rocky Mountain states, or the Pacific Slope, to journey across the continent to be present—albeit the record for attendance on the part of the members from such areas is excellent. Such considerations do not weigh so heavily in the nearer districts, save tha't it sometimes happens that a man who can fulfil the duty rather easily will tend to slight it merely because it does require so little effort.

In any case it is not amiss to invite active and intelligent attention to this matter at this time, because the filling of the Council with active and interested men is a great desideratum. The Council has come to be a sort of Congress of the alumni, transacting in their name the various items of business which it is no longer practicable to handle by resort to the ancient method of a general meeting at Hanover at Commencement—a method which served fairly well when the number of the alumni was small and when the duties devolving upon them were few and inconsiderable.

WHAT DID WEBSTER SAY?

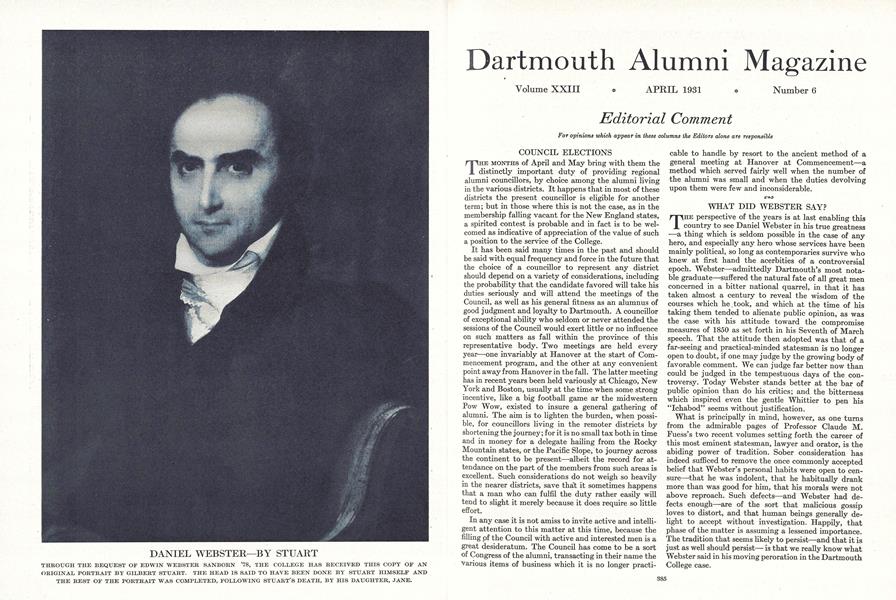

THE perspective of the years is at last enabling this country to see Daniel Webster in his true greatness —a thing which is seldom possible in the case of any hero, and especially any hero whose services have been mainly political, so long as contemporaries survive who knew at first hand the acerbities of a controversial epoch. Webster—admittedly Dartmouth's most notable graduate—suffered the natural fate of all great men concerned in a bitter national quarrel, in that it has taken almost a century to reveal the wisdom of the courses which he.took, and which at the time of his taking them tended to alienate public opinion, as was the case with his attitude toward the compromise measures of 1850 as set forth in his Seventh of March speech. That the attitude then adopted was that of a far-seeing and practical-minded statesman is no longer open to doubt, if one may judge by the growing body of favorable comment. We can judge far better now than could be judged in the tempestuous days of the controversy. Today Webster stands better at the bar of public opinion than do his critics; and the bitterness which inspired even the gentle Whittier to pen his "Ichabod" seems without justification.

What is principally in mind, however, as one turns from the admirable pages of Professor Claude M. Fuess's two recent volumes setting forth the career of this most eminent statesman, lawyer and orator, is the abiding power of tradition. Sober consideration has indeed sufficed to remove the once commonly accepted belief that Webster's personal habits were open to censure—that he was indolent, that he habitually drank more than was good for him, that his morals were not above reproach. Such defects—and Webster had defects enough—are of the sort that malicious gossip loves to distort, and that human beings generally delight to accept without investigation. Happily, that phase of the matter is assuming a lessened importance. The tradition that seems likely to persist—and that it is just as well should persist is that we really know what Webster said in his moving peroration in the Dartmouth College case.

That tie closed his appeal with something particularly emotional is undoubted. The statement is made in a dozen comments by those who wrote as contemporaries. But it is a very curious fact that the exact words said to have been used by the counsel, for the exactitude of which most Dartmouth men would cheerfully go to the stake, were not transcribed at the time and that for them we must turn t.o a private letter, written something like 35 years later by a man who heard them, but who must, after so long a time, have had rather a vague recollection, to say the least. Try yourself to recall the speech of some notable personage that you heard a generation ago, and write out a verbatim report of it!

March was for Webster, as for Caesar, a momentous month. It was on the 7th of March, 1850, that he delivered his famous speech on the compromise. It was on the 10th of March, 1818, that he had argued so effectively for his alma mater. But it was not until 1853, when Webster was in his grave, that Professor Chauncey Goodrich of Yale, who had listened to the arguments in the Dartmouth College case, wrote out his recollection of them in a letter to Rufus Choate—who accepted the quotation as substantially accurate, despite the strong antecedent improbability, and repeated the words in an address in the old College Church.

If Webster never said it, he might well have done. At all events the tone was Websterian, and the tradition has become inalterably fixed. After all, why not? The world has long accepted the oration which Thucydides put in the mouth of Pericles. But it is interesting to know, as Professor Fuess points out, that had it not been for this letter of Goodrich to Choate, written by a man 63 years old and 35 years after the event, the purport of Webster's emotional appeal to the judges might have been utterly lost to a world which would have been the poorer in consequence. Let us quote familiar words, which to the Dartmouth fellowship have something that savors almost of sanctity:

"This, sir, is my case. It is the case, not merely of the humble institution; it is the case of every college in our land. It is more. It is the case of every eleemosynary institution throughout our country, of all those great charities founded by the piety of our ancestors to alleviate human misery, and scatter blessings along the pathway of human life. . . . Sir, you may destroy this little institution; it is weak; it is in your hands! You may put it out—but if you do, you must carry on your work. You must extinguish, one after another, all those great lights of science which for more than a century have thrown their radiance over the land! It is, sir, as I have said, a small college—and yet there are those who love it.". . .

According to Professor Goodrich, Chief Justice Marshall was visibly stirred and many present were openly weeping—but Webster was not done. Pausing with the true orator's instinct and fixing a scornful eye on the advocates of the opposing side, he continued:

"Sir, I know not how others may feel; but, for myself, when I see my alma mater surrounded, like Caesar in the senate-house, by those who are reiterating stab upon stab, I would not, for this right hand, have her turn to me and say—'Et tu quoque, mi fili!'—'and thou, too, my son!' "

As the Italians say, "Se non evero, I ben' itovato." It is Webster, filtered through Goodrich; but it undoubtedly is very like what was said that March day in the Supreme court, and since we have no other source of information it must stand, as it is well worthy to do, for all time as Webster's own. Did emotion, or logic, weigh the more with the justices that day? Who knows—or greatly cares? We won!

WHY WASTE THE TIME?

THAT entertaining writer, Hendrik Willem Van Loon (which we believe is pronounced Van Loan), broadcasts to a listening earth through the Wisconsin AlumniMagazine that he has asked himself whether he will send his two sons to college and has found the answer to be in the negative.

The reasons are not especially novel. They boil down to the statement that as colleges now go it is wasted time to attend them. Does one require information? It is at hand in countless enclycopaedias. Does one require to be trained to think independently, to question intelligently, "to doubt remorselessly every fact that offers itself for our inspection?" The colleges do not teach one to think. "They lack inner cohesion and intellectual discipline," and they leave the average boy and girl "totally unfit for the harsh business of living—and even more unfit for the harsher business of making a living." Ask yourself, he urges, "How many of my professors really gave me something that stuck?"

This seems nothing more than the commonplace outburst of the rebellious Intellectual, who insists that things are as bad as can be in educational circles. Since college professors are such a poor lot, Mr. Van Loon concludes his sons "would better go lobster-fishing with Jack Mulhaley. Jack is not familiar with the split and unsplit infinitive, but he does know lobsters and can talk of them with feeling and enthusiasm." It sounds like a wonderful school in which to learn to "think independently, question intelligently, and doubt remorselessly every fact that presents itself!" A lobsterpot with Jack Mulhaley at one end and a Van Loon at the other seems to be the modern equivalent of Mark Hopkins's log.

Somehow one feels vaguely that there's a middle ground between insisting that the colleges are perfect and condemning them as worthless. Beyond doubt the professors that give one something that can be pointed to as having "stuck" are rather rare; but it by no means follows that there has been no unidentified accretion from the contact with the others. Much showy nonsense is talked by the critics, and one greatly fears that there's a modicum thereof in the caustic reflections of the excellent Van Loon. There have been times when, scanning the lush meadows of Academic Freedom, we have felt that the one thing the student of the present day was being most surely taught to do was to "doubt remorselessly every fact that presented itself for inspection," even when the massed evidence of human experience indicated that to doubt would be rather sillier than to believe. But possibly Mr. Van Loon would say that anyone discovering what seemed a lack of intelligent thought in his own doctrines must charge it to the inadequacy of American educational theory at Cornell, from which conservative university Who's Who says he received his A.B. in 1905.

We cannot bring ourselves to think so meanly of our colleges as all that—certainly not to the point of assuming that there is more stimulus toward constructive independent thought in pursuing a course in practical lobster fishing. However, this is the easy way of being superior in this current day, when everybody's doing it and when it takes rather an extreme statement to attract notice. Besides, these very critics are themselves the product of a system which they aver is incapable of inspiring anybody to think accurately—so doubtless they ought not to be blamed for piling up cumulative proof.

PUBLIC OR PRIVATE SCHOOLS?

IT is the virtually universal testimony of those who have investigated the question that the college students whose preparation was secured in the public schools of the country as a rule stand better, scholastically, than do those whose preparation was obtained in the private schools. It is well, however, to bear in mind that this may be a misleading statement and that it is easily possible it may do a serious injustice to the private schools.

All generalizations are dangerous, but this one is particularly so. One should consider that the young people who go to college from the public schools are ordinarily the picked few—the few possessing unusual powers and distinguished by greater initiative impulses —whereas among those who have sought the private schools for their preparation, going to college is the general rule for all. In other words, the boy who comes to a college from a public school in these days is pretty sure to be one who really craves a college education and who is eager to make the utmost of it; whereas the boy who comes from a private school is coming to college more as a matter of course and may not possess the same incentives, though he may have quite as good capacities, to shine.

The occasional propensity among public school products to outstrip the products of the private schools, then, is not conclusive evidence that the preparation offered by the public schools is better. Indeed it would seem a very unlikely proposition that public school preparation is even so good as that which a similarly minded lad would derive from a private school. The difference, if any, is probably in the boys and their environment in each case. Times have changed a great deal in the past score of years. One recalls the time when if a boy went to a private school, it was often because he could not keep up in the public schoolswhich is certainly not the case at present. The private schools are not recruited from the backward and the lazy to the extent they once were, nor are they altogether composed of the wealthy and indifferent. The teaching in them ought to be, and unquestionably is, better than that in public schools where politics holds sway. If it is still true that the boys from private schools show to less advantage scholastically than those from public schools, the reason is most probably in the boys themselves, rather than in the schools.

THE VALUE OF SIDE ISSUES

A RATHER bewildering but extremely interesting bulletin has lately been issued by Purdue University (Lafayette, Indiana) in the course of which are set forth the summarized opinions of a selected list of successful graduates concerning various forms of extracurricular activities and their value as supplementing the curriculum in the education of the student.

The canvass appears to have covered a field embracing something like 230 men, whose names appear in Who's Who and other standard works, plus some chosen by the university deans and members of the faculty as sufficiently successful in life to warrant their having opinions of weight. The questionnaires sent them seem to have covered various lines, including the general desirability of a college education for such as must count the pennies, and the best course for such to adopt as a means of financing their educational career. But what it is proposed to consider briefly here is the massed opinions on the value of outside activities, into which matter the report goes at considerable length.

Out of 192 men submitting replies on this point, 27 (14%) held that extra-curricular activities of all kinds were of "very great" value; 80 (41.6%), that they were of "great" value; and 67 (35%), of "perceptible" worth to them. As against these, 16 reported that they felt the extra-curricular interests were of negligible effect for good; and only two stated that they regarded them as positively detrimental.

Particularizing, the various sorts of activities have afforded material for differentiation. A total of 223 replies came from men who had been athletes or nonathletes during their own course; and their feeling with respect to the value of athletic activities in education is interesting. Naturally those who had been in sports rated the value higher than did those who had not been. Still five out of 55 ex-athletes admitted that they regarded their athletic experiences as of practically no value at all, as against one enthusiast who rated it as worth to him as much as 35 per cent. The mean of the values set by the ex-athletes was 13.46, as against a value of 9.32 set by graduates who had no athletic experiences in college. The mean of the means is given as 10.34.

"Social" activities are also considered in the table. One enthusiast for these went on record as believing that such had been worth from 70 to 75 per cent to him but the great bulk voted to list such interests as rating from 5 to 10 per cent, and the mean of all the opinions was 12.20. Activities through student organizations (non-athletic) received a mean percentage of 14.51, with a mean total for all three (athletic, social and student organizations) of 33.48 per cent. "Contact with professors" was also considered and was weighted in the schedule at 23.68 per cent on the average. A flattering estimate of 39.58 per cent was assigned to the advantage gained "from books." From outside speakers visiting the college, the majority vote estimated the benefit to be 10.54 per cent—about the same as the mean for the benefit derived from athletics.

All this is sheer guess-work, of course, from a veryfew men; but there is reason to believe it represents a fairly accurate opinion and one which would be duplicated by any similar investigation. To sum it up, these men indicate that about 40 per cent of the value of their college experience outside the classroom came from books, almost 25 per cent more from their contact with professors—and the rest from other extra-curricular activities, including athletics, student organizations, fraternities and the like.

In addition there is a table indicating that, of 219 men interrogated, one-third had chosen their vocations before going to college, and that half of them did not decide until after they had graduated. Only three chose their life work during freshman year, six in sophomore year, a dozen in junior year, and 15 in senior year. This again seems a fairly accurate cross-section of American collegiate experience, unless it be questioned that so many as 33.3 per cent usually know before entering college what they expect to do when they come out—and actually do it.

A TIME TO BE SUSPICIOUS

A QUITE insidious wolf, clothed very plausibly in fictitious fleece, has been going about of late fraudulently obtaining money from Dartmouth men who were too charitab'e to disbelieve his ingenious sob stories and too good Dartmouth men to refuse to help another Dartmouth man, or the son or brother of one, in distress. During the last several months the MAGAZINE has contained letters on the one hand from Dartmouth men who have been fraudulently impersonated and on the other hand from those who have been generously fleeced, warning the Dartmouth public against this swindling imposter who, we confidently assume, never sojourned under our Hanover elms but who, nevertheless, has a beguiling intimacy with Dartmouth names and places.

These frauds may have been perpetrated by one man with as many personalities as Lon Chaney and as many names as the Prince of Wales, or they may be the work of several able swindling craftsmen fortuitously similar in their approach. There is a fairly unanimous description of the imposter as a well-mannered, carefully dressed, plausible young man in the middle twenties. Usually he is the son of your classmate, occasionally he is friend of your son in college, and sometimes he assumes nothing more than the character of an ambitious, clean-cut young chap working his way through college. He is usually going back to college from some appropriate place in the United States. With glibness and nonchalance he will reel off the names of people you know, or ought to know. He is pursued by a hostile fate, which continually subjects him to automobile accidents, unjust arrests, pickpockets, and other perils and misfortunes with which this life is fraught. But the sun will shine again if you will be kind enough to lend him a hundred dollars to enable him to get to Hanover, or home, or the Harvard game; you will have the eternal gratitude of himself and of his father, your classmate, or of your son, his college chum; and of course a check will be mailed to you immediately. A thousand thanks, sir.—And that will be the last that you will see of this Mr. Bowers, or Jenks, or Perkins, or of your hundred dollars.

And so it would seem regrettably desirable that generosity be tempered with suspicion, at least to the extent that it be not misplaced and hopeful of the result that the imposter, or imposters, be detected and punished. Many a Dartmouth man in genuine temporary distress has been helped out of difficulty by other sons of the College all over the world. This eagerness to come to the rescue is a too valuable Dartmouth attribute to be undermined by swindling and undetected fraud.

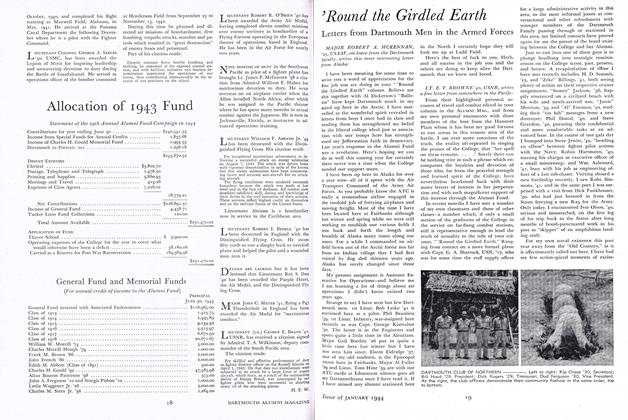

Early in April the first call will go out for the Alumni Fund campaign of 1931. Its goal is $135,000. An early response is the best answer alumni can give to the question of Dartmouth's possibility of financial success this year. It may be argued that those who send in early gifts thereby reduce, to a great degree, the time-consuming efforts of class agents who are faced each year with the pleasant but arduous task of directing their own class campaigns.

To all alumni immediate subscription to the Fund should be more attractive than previously since the three major mailing pieces are to be sent to all—regardless of whether or not they may have already sent in gifts. The Alumni Fund committee feels that the literature which will distinguish this year's campaign will be of such general interest to alumni and may even be prized so highly by them that it should be made available to all. So an early reply to the first broadside will prevent no one from receiving the remaining two pieces.

We are inclined to think that the loyalty with which Dartmouth men rally to the support of their Alumni Fund each year is not to be infringed upon by a dubious business outlook in any one year. In past years, when prosperity seemed to be the order of the day, there were many to whom the sacrifice of a small gift to the Fund following upon sickness, misfortune, or hard luck, was a mark of true devotion. That many gifts have been made by men under such circumstances is an evidence of the support the Fund may expect, whether conditions are good or otherwise.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

April 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleHow Ben Ames Williams Writes a Book

April 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

April 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

April 1931 -

Article

ArticleHow The New Library Furthers Scholarship

April 1931 By Arnold K. Borden -

Article

ArticleWebster Did Not Tear Up His Diploma

April 1931 By T. A. Merrill

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MARCH 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

January 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorRound the Girdled Earth

October 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWinter and Rough Weather

DECEMBER 1983 By Doug Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Giridled Earth

August 1944 By H. F. W. -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorYou could say a woman started it all.

MARCH 1997 By Karen Endicott