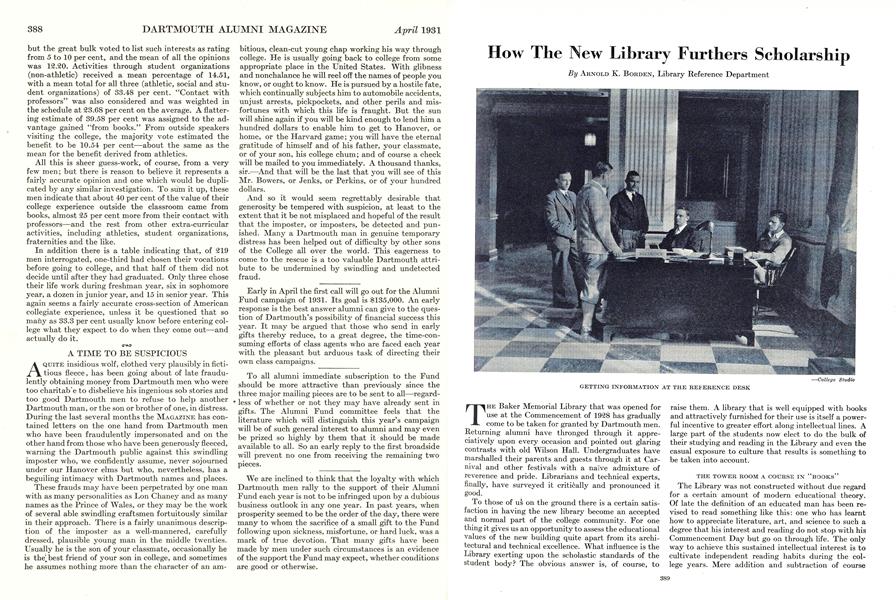

THE Baker Memorial Library that was opened for use at the Commencement of 1928 has gradually come to be taken for granted by Dartmouth men. Returning alumni have thronged through it appreciatively upon every occasion and pointed out glaring contrasts with old Wilson Hall. Undergraduates have marshalled their parents and guests through it at Carnival and other festivals with a naive admixture of reverence and pride. Librarians and technical experts, finally, have surveyed it critically and pronounced it good.

To those of us on the ground there is a certain satisfaction in having the new library become an accepted and normal part of the college community. For one thing it gives us an opportunity to assess the educational values of the new building quite apart from its architectural and technical excellence. What influence is the Library exerting upon the scholastic standards of the student body? The obvious answer is, of course, to raise them. A library that is well equipped with books and attractively furnished for their use is itself a powerful incentive to greater effort along intellectual lines. A large part of the students now elect to do the bulk of their studying and reading in the Library and even the casual exposure to culture that results is something to be taken into account.

THE TOWER ROOM A COURSE IV "BOOKS"

The Library was not constructed without due regard for a certain amount of modern educational theory. Of late the definition of an educated man has been revised to read something like this: one who has learnt how to appreciate literature, art, and science to such a degree that his interest and reading do not stop with his Commencement Day but go on through life. The only way to achieve this sustained intellectual interest is to cultivate independent reading habits during the college years. Mere addition and subtraction of course credits are no longer looked upon as worthy mathematical exercises. In the full glare of these newer educational conceptions library buildings and policies have had to be profoundly modified and changed. The first answer to the challenge at Dartmouth is the Tower Room. Here every inducement has been offered for making reading a pleasure and by making it pleasurable to make it an ingrained habit. The inducements are comfort and beauty in the furnishings and books that are carefully selected for universality of appeal or permanent significance in the history of culture. Now and then of late we hear of projects for extending the scope of adult education to include college alumni. Some institutions have inaugurated summer courses to this end. The need for such a move implies a confession of weakness. If the educative process to which a college has subjected a student for four years has produced a really educated gentleman, it need have no fear that he will desert the realm of books. The lack of books has the same effect upon him as the lack of air—suffocation. Days devoted to quiet reading in the Tower Room should help to cultivate a taste for literature that time will not unlearn.

Another old theory that education consisted largely of unpleasant discipline of the several faculties into which the mind was supposed to be resolvable has given place to the idea that mental discipline comes only from progressive immersion in that subject which is of consuming interest to the individual student. From the point of view of college administration this has meant the establishment of the honors system and comprehensive examinations. This new educational psychology has also been of fundamental importance to libraries.

It should be obvious to a careful discriminator that the Tower Room is designed to be an invitation to the general reader and literary nomad rather than to the specialist—its contents range rather widely over the field of knowledge without seeking to be profound in any. Of course it must be admitted that where the general reader leaves off and the specialist begins in the case of undergraduates is a difficult line to demarcate. At any rate the Library and College are answering the problems of specialization in other ways. The Carpenter Art building, Sanborn English House, the Ferguson Room (on the top floor of the Library recently made available to honors students in the social sciences, a large and inclusive group) have become centers of study and work for students pursuing special interests. These various centers are intimately associated with the Library and in the case of Sanborn and the Ferguson Room most of the books found there are duplicates. On the top floor of the Library, in addition, is a large number of seminar rooms, where, in accordance with the best educational procedure, teachers and students are afforded the opportunity to meet in small groups and come in close personal contact with each other. All these things taken together—the Tower Room, the special centers for study, and the seminar rooms—form a valuable integration in the way of library facilities of the college's intellectual activities.

USING ONE'S INITIATIVE

In addition to providing an environment conducive to study, the Library also seeks to place a certain amount of reliance upon the individual student. There are those, of course, who claim that the modern college tends to pamper the undergraduate too much and by exercising too much parental supervision over him to delay his intellectual maturity and independence. The Library counteracts any tendency in this direction in several ways. In the first place it was not constructed in such a way as to make a system of policing and rigid checkup feasible. The burden of proof for the proper use of the freedom granted rests squarely on the shoulders of the undergraduates. The stacks are open to all comers and students are expected to learn how to locate their own books. This ability in itself presupposes an understanding of the catalogue of the Library. The arrangement of the reference room is such that its volumes press upon the attention of the passer-by and with the instruction available make for a certain training in the use of books as tools and the finding of information. To the end that facility in this direction will be acquired early in the college course the reference department, of which the writer is a member, undertakes at the beginning of the college year to educate the freshmen in the use of the Library. The day before college opens is reserved by the Dean as Library Day and the freshmen come in reasonably small groups throughout the day to receive instruction. Then in the course of the next month the instructors in the freshmen English courses cooperate with us by distributing library problems which are designed to illustrate the practical significance of the preceding lectures. In this and other ways the Library seeks to develop a certain amount of self-help among the students.

In the last analysis the Library has taken upon itself in recent years more and more of the educative function. Formerly libraries were regarded mere'y as store-houses for books, the circulation of which must be jealously guarded. Today libraries spend increasingly larger portions of their income on agencies which seek to elucidate the contents of their collections. Indeed this is altogether necessary—the number of books has attained such bewildering dimensions that the amateur cannot thread his own way with profit. It is one thing to store books; it is quite another to make them available.

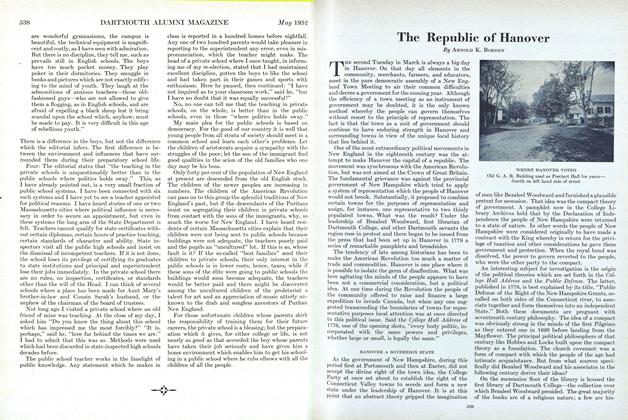

The first agency that was created to give the needed counsel and guidance is the reference department. In seeking to be a general clearing house of knowledge this department has its obvious limitations, but from the days when the writer was the only member to the present when three members answer fifty or more questions a day the work of interpreting the Library has continuously expanded. About three-fourths of the questions emanate from undergraduates who are naturally perplexed as to what to read, how to find specific facts and sources of information for theses, and how to judge critically the mass of material available. It is a long way from suggesting a good book on the social background of Piers the Plowman to finding the number of potatoes exported from the United States in 1950; but one question follows hard on another in the reference work routine. In a similar way, although more from the point of view of the improvement of leisure, the attendants in the Tower Room seek to give direction to reading.

FUNCTIONS OF OFFICERS

One further significant addition was made a year ago to the library staff when the post of "bibliographer" was created. The object of this appointment was the facilitation of research, particularly among members of the faculty. It is a fact that most scholars have an inadequate understanding of the bibliographical resources at their disposal. Perhaps there is no particular reason why they should be expected to be acquainted with them. Bibliography is in a sense machinery which facilitates the approach to knowledge, but which requires special training to handle it most effectively. This is a point, in other words, where the scholar generally erally obtains the best results by making contact with a research librarian. Accordingly, those doing scholarly research in the community are finding that the new bibliographical agencies at their command promote and expedite work.

What is the justification for this widening range of library service? It is the fuller recognition that the Library is fundamentally significant from an educational point of view. Books are the beginning and end of all learning, and therefore it is within the bailiwick of the librarian to stimulate their correct use and appreciation and to make them yield the maximum of knowledge and culture. A recent letter to the writer from a prominent scientist strikes the nub of the matter: "If we could spend one-tenth of the vigor in making efficient use of our fine collections that we expend in collecting them and talking about them, I think that the progress of learning might be better assured." In other words, if the Library is able to contribute anything to the development of permanent habits of reading and thought or to the advancement of scholarship and research, it is only the part of wisdom to exert itself to these ends.

The work of the class room and of the Library necessarily overlaps. When reading assignments are specific, the Library merely provides the books and a quiet place to study except as it may be called upon to illuminate a difficult text by suggesting further reading. When an instructor assigns a subject for investigation rather than a particular text the Library plays a more prominent part by helping the student to unearth and select material—always, of course, stopping short of doing too much of the work for him and destroying his self-reliance. But while there is this overlapping on the part of the Library, there is no usurpation of the teaching function. The Library has merely become an integral part of the educative process which today includes something beyond the recitation room—all of which suggests that it is a long journey from the days when the Dartmouth Librarian was reported to have looked out upon undergraduates from an iron cage with great distrust and suspicion.

GETTING INFORMATION AT THE REFERENCE DESK

REFERENCE ROOM

MAGAZINE ROOM

Library Reference Department

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

April 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

April 1931 -

Article

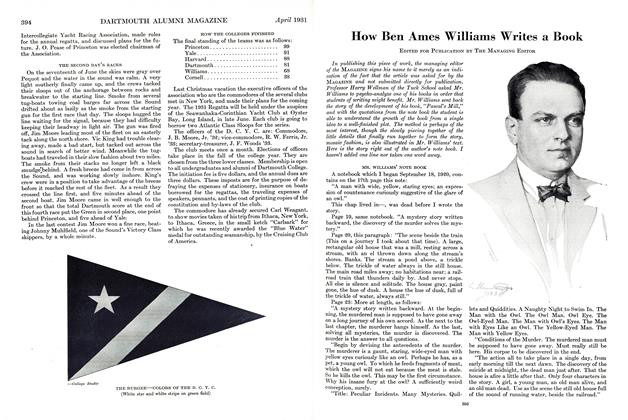

ArticleHow Ben Ames Williams Writes a Book

April 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

April 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

April 1931 -

Article

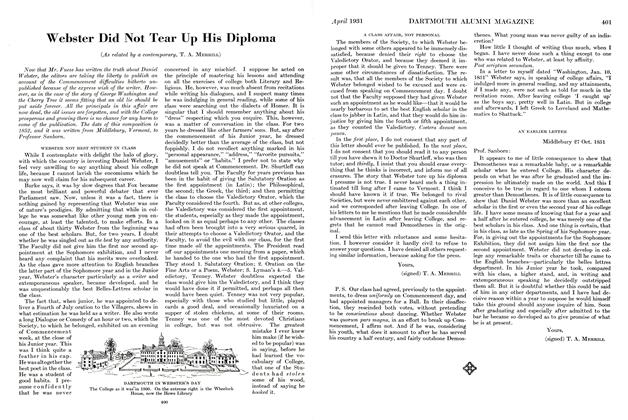

ArticleWebster Did Not Tear Up His Diploma

April 1931 By T. A. Merrill

Arnold K. Borden

Article

-

Article

ArticleBUST OF WEBSTER IN HALL OF FAME

DECEMBER 1927 -

Article

ArticleIN THE NEW SANBORN HOUSE

MAY 1930 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

Nov/Dec 2007 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Indians

JUNE 1930 By Leon B. Richardson -

Article

ArticleLet Them Eat Spinach?

August 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleDoctor Howland Retires

April 1943 By Stanley E. Johnson.