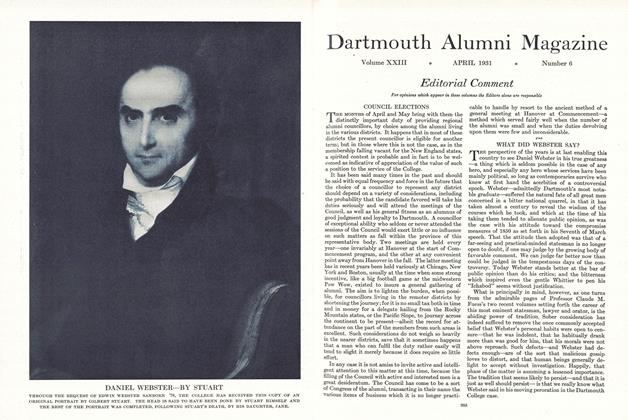

Now that Mr. Fuess has written the truth about DanielWebster, the editors are taking the liberty to publish anaccount of the Commencement difficulties hitherto unpublished because of the express wish of the writer. However, as in the case of the story of George Washington andthe Cherry Tree it seems fitting that an old lie should beput aside forever. All the principals in this affair arenow dead, the old issues are forgotten, and with the Collegeprosperous and growing there is no chance for any harm tocome of the publication. The date of this composition is1852, and it was written from Middlebury, Vermont, toProfessor Sanborn.

WEBSTER NOT BEST STUDENT IN CLASS

While I contemplate with delight the halo of glory, with which the country is investing Daniel Webster, I feel very unwilling to say anything about his college life, because I cannot lavish the encomiums which he may now well claim for his subsequent career.

Burke says, it was by slow degrees that Fox became the most brilliant and powerful debater that ever Parliament saw. Now, unless it was a fact, there is nothing gained by representing that Webster was one of nature's prodigies. By admitting that while in college he was somewhat like other young men you encourage, at least the talented, to make efforts. In a class of about thirty Webster from the beginning was one of the best scholars. But, for two years, I doubt whether he was singled out as the best by any authority. The Faculty did not give him the first nor second appointment at the Sophomore exhibition, and I never heard any complaint that his merits were overlooked. As the class gave more attention to English branches the latter part of the Sophomore year and in the Junior year, Webster's character particularly as a writer and extemporaneous speaker, became developed, and he was unquestionably the best Belles-Lettres scholar in the class.

The fact that, when junior, he was appointed to deliver a Fourth of July oration to the Villagers, shews in what estimation he was held as a writer. He also wrote a long Dialogue or Comedy of an hour or two, which the Society, to which he belonged, exhibited on an evening of Commencement week, at the close of his Junior year. This was I think quite a feather in his cap. He was altogether the best poet in the class. He was a student of good habits. I presume confidently that he was never concerned in any mischief. I suppose he acted on the principle of mastering his lessons and attending on all the exercises of college both Literary and Religious. He, however, was much absent from recitations while writing his dialogues, and I suspect many times he was indulging in general reading, while some of his class were searching out the dialects of Homer. It is singular that I should remember anything about his "dress" respecting which you enquire. This, however, was a matter of conversation in the class. For two years he dressed like other farmers' sons. But, say after the commencement of his Junior year, he dressed decidedly better than the average of the class, but not foppishly. I do not recollect anything marked in his "personal appearance," "address," "favorite pursuits," "amusements" or "habits." I prefer not to state why he did not speak at Commencement. Dr. Shurtleff can doubtless tell you. The Faculty for years previous has been in the habit of giving the Salutatory Oration as the first appointment (in Latin); the Philosophical, the second; the Greek, the third; and then permitting the class to choose the Valedictory Orator, which the Faculty considered the fourth. But as, at other colleges, the Valedictory was considered the first appointment, the students, especially as they made the appointment, looked on it as equal perhaps to any other. The classes had often been brought into a very serious quarrel, in their attempts to choose a Valedictory Orator, and the Faculty, to avoid the evil with our class, for the first time made all the appointments. The President read off our appointments one morning from a paper, which he handed to the one who had the first appointment. They stood 1. Salutatory Oration; 2. Oration on the Fine Arts or a Poem, Webster; 3. Lyman's 4.—5. Valedictory, Tenney. Webster doubtless expected the class would give him the Valedictory, and I think they would have done it if permitted, and perhaps all then would have been quiet. Tenney was not very popular, especially with those who studied but little, played cards a good deal, and occasionally luxuriated on a supper of stolen chickens, at some of their rooms. Tenney was one of the most devoted Christians in college, but was not obtrusive. The greatest mistake I ever knew him make (if he wished to be popular) was in saying, before he had learned the vocabulary of College, that one of the Students had stolen some of his wood, instead of saying he hooked it.

A CLASS AFFAIR, NOT PERSONAL

The members of the Society, to which Webster belonged with some others appeared to be immensely dissatisfied, because denied their right to choose the Valedictory Orator, and because they deemed it improper that it should be given to Tenney. There were some other circumstances of dissatisfaction. The result was, that all the members of the Society to which Webster belonged wished to be excused and were excused from speaking on Commencement day. I doubt not that the Faculty supposed they had given Webster such an appointment as he would like—that it would be nearly barbarous to set the best English scholar in the class to jabber in Latin, and that they would do him injustice by giving him the fourth or fifth appointment, as they counted the Valedictory. Coetera desunt nonpauca.

In the first place, I do not consent that any part of this letter should ever be published. In the next place, I do not consent that you should read it to any person till you have shewn it to Doctor Shurtleff, who was then tutor; and thirdly, I insist that you should erase everything that he thinks is incorrect, and inform me of all erasures. The story that Webster tore up his diploma I presume is not true. I never heard such a thing intimated till long after I came to Vermont. I think I should have known it if true. We belonged to rival Societies, but were never embittered against each other, and we corresponded after leaving College. In one of his letters to me he mentions that he made considerable advancement in Latin after leaving College, and regrets that he cannot read Demosthenes in the original.

I send this letter with reluctance and some hesitation. I however consider it hardly civil to refuse to answer your questions. I have denied all others requesting similar information, because asking for the press.

Yours, (signed) T. A. MERRILL

P. S. Our class had agreed, previously to the appointments, to dress uniformly on Commencement day, and had appointed managers for a Ball. In their disaffection, they rescinded both votes, without pretending to be conscientious about dancing. Whether Webster was quorum pars magna, in an effort to break up Commencement, I affirm not. And if he was, considering his youth, what does it amount to after he has served his country a half century, and fairly outshone Demosthenes. What young man was never guilty of an indiscretion?

How little I thought of writing thus much, when I began. I have never done such a thing except to one who was related to Webster, at least by affinity. Post scriptum secundum.

In a letter to myself dated "Washington, Jan. 10, 1851" Webster says, in speaking of college affairs, "I indulged more in general reading, and my attainments, if I made any, were not such as told for much in the recitation room. After leaving college 'I caught up' as the boys say, pretty well in Latin. But in college and afterwards, I left Greek to Loveland and Mathe- matics to Shattuck."

AN EARLIER LETTER

Middlebury 27 Oct. 1851

Prof. Sanborn: It appears to me of little consequence to shew that Demosthenes was a remarkable baby, or a remarkable scholar when he entered College. His character depends on what he was after he graduated and the impression he ultimately made on the world. And this I conceive to be true in regard to one whom I esteem greater than Demosthenes. It is of little consequence to shew that Daniel Webster was more than an excellent scholar in the first or even the second year of his college life. I have some means of knowing that for a year and a half after he entered college, he was merely one of the best scholars in his class. And one thing is certain, that in his class, as late as the Spring of his Sophomore year. For, in giving out the appointments for the Sophomore Exhibition, they did not assign him the first nor the second appointment. Webster did not develop in college any remarkable traits or character till he came to the English branches—particularly the belles lettres department. In his Junior year he took, compared with his class, a higher stand, and, in writing and extemporaneous speaking he decidedly outstripped them all. But it is doubtful whether this could be said of him in any other departments, and I have had decisive reason within a year to suppose he would himself take this ground should anyone inquire of him. Soon after graduating and especially after admitted to the bar he became so developed as to give promise of what he is at present.

Yours, (signed) T. A. MERRILL

DARTMOUTH IN WEBSTER'S DAY The College as it was in 1800. On the extreme right is the Wheelock House, now the Howe Library

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

April 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

April 1931 -

Article

ArticleHow Ben Ames Williams Writes a Book

April 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

April 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

April 1931 -

Article

ArticleHow The New Library Furthers Scholarship

April 1931 By Arnold K. Borden