a play of American folklore in three acts with a prologue, by Henry Bailey Stevens, 1912. Walter H. Baker Cos. Mr. Stevens has had the happy idea of bringing together in a play two of the raciest of America's legendary characters as rivals in love. Appleseed, visionary and poet, a fanatic with the mission of creating value and beauty for the future by sowing appleseeds throughout the land, comes to a settler's cabin in the forest, and casts his romantic spell on the daughter. He makes clear, before leaving, that for him there can be no question of love until allegiance to his ideal of beauty is proven in the fair object of his desire. He leaves with a promise to return. Bunyan, represented as a blatant Canuck Marco, is less fastidious. He devastates the forest with a buzz-saw, amasses a fortune, easily wins the father, and dazzles the reluctant daughter with dresses and jewels. Mr. Stevens does not, however, let the expected happen. Gertrude does not throw over the certainty of wealth for Appleseed's romance. In fact, she has one of the dresses on when John puts in his appearance. Perhaps she has expected this to satisfy his rigid test as to love of beauty. Certainly she still would prefer John without gifts to the uncomely Paul with all his wealth. But weightier matters prevent. She has overheard John as he made protests of eternal devotion to his ideal of beauty, appearing to him and to the audience in the person of a Dryad living in a gorgeous apple tree near the father's cabin. His "mooning" as she calls it, and his coldness quickly lead to her decision. Partnership in such an ideal is not for her. She has clearly failed in the test of beauty and chooses Paul on the spot. She knows she must stifle her real love in so doing and as a symbol of sacrifice she sternly orders Bunyan to cut down the apple tree planted by Daniel Boone the last thing of beauty within sight. Paul is grieved, it appears, only because an apple tree is now dead.

To this point the play has had dramatic breadth and theatrical appeal, but it has lacked excitement. This is now amply furnished by a midnight raid of Indians in revenge for the desecration of the tree and as a protest against Bunyanism in general. John presently appears as a hero of peace, calms the rage of the savage about to fire the cabin and scalp the resisting Paul, and exhibits, with the aid of a stereopticon, a vision of future orchards in bloom where now all is waste. He raises a spade in defiance of knife, gun, and axe. Bunyan and Gertrude think it best to go West and leave John his Dryad and his friendly savage to go on planting beauty

Along the Monongahela Down the Ohio Along the Muskingum, the Mohican and the Wabash, Where the wild haw and the morning glory shall greet us.

It is a highly entertaining medley of poetry, fantasy, and grotesque humor. Paul Bunyan as ancestor of Babbits is plausible and amusing and should make a good acting part. His legendary exploits are delivered by proxy through the mouth of Inkslinger, who recites them at great length in free verse as a prelude to love. John, however, is clearly the author's favorite, but is a more serious challenge to the dramatist. His note of romance and his lyric passages afford a pleasing if daring contrast. Through him the writer a little too obviously and persistently reiterates the message of the play. What is more, John's action is so slightly integrated with the play as hardly to afford the dramatic tensity expected in the later scenes. It is, however, refreshing to have the poetic values thus introduced, making possible a play in which the more usual values of the triangle situation are not stressed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

April 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

April 1931 -

Article

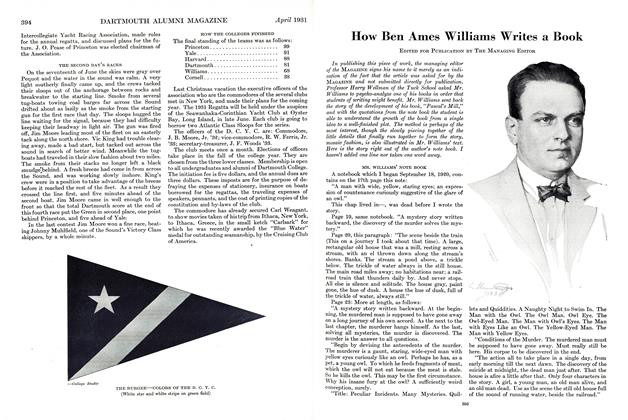

ArticleHow Ben Ames Williams Writes a Book

April 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

April 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

April 1931 -

Article

ArticleHow The New Library Furthers Scholarship

April 1931 By Arnold K. Borden

Books

-

Books

BooksFURNITURE MARKETING.

MAY 1957 By CLYDE E. DANKERT -

Books

BooksNOT FOR HYPOCHONDRIACS WE TAKE TO BED

April 1931 By Herbert F. West -

Books

BooksANNAPOLIS, AHOY!

January 1946 By Herbert F. West Jr. (aged 11) -

Books

BooksIT'S A FREE COUNTRY

October 1945 By Herbert R. West '22. -

Books

BooksTHE THREAD OF ARIADNE: THE LABRYINTH OF THE CALENDAR OF MINOS.

DECEMBER 1972 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksA STUDENT'S PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION

May 1935 By Roy B. Chamberlin