By Donaldson Jordan and Edwin J. Pratt. Boston, 1931. Houghton Mifflin Company.

This volume might well have had the subtitle, "A Study of Public Opinion," for it is with European public opinion that the authors are primarily concerned. They have endeavored to show what the people of Europe thought about the American Civil War, and how this opinion, along with economic factors, affected affairs in Europe.

The book is the product of two independent investigations. The study of British opinion was made by Mr. Jordan while a candidate for the doctorate at Harvard; Mr. Pratt's study of continental opinion was made during his residence at Oxford. At the suggestion of JProfessor S. E. Morison, who read both dissertations, they were rewritten in collaboration and brought together in a single volume. The identity of each study, however, has been maintained. Such arrangement is apt to have shortcomings due to differences in method of approach, style and emphasis. These the authors have not escaped. But one gets a good analysis of the drift of opinion abroad and its effects, especially in the case of England, and that is what counts most for the reader.

The major portion of the text is devoted to Great Britain. This is perhaps not unreasonable: Britain was more directly affected by the war than any other country, and it was her course that gave the Washington authorities the greatest concern. Also to a very considerable extent the continental chancellories took their cue on American affairs from Downing Street. In the course of his extensive researches at home and in England, Mr. Jordan has tested the views and the influence of representative English newspapers, the Anglican and Nonconformist clergy, the literary men, industrialists, politicians, societies and the great classes into which Britain is divided. It is not possible here in brief compass to analyze his findings, but it is of interest to note that they show that the most consistent friends of the North were those who were most interested in political and social reform at home. In the main they were recruited from the laboring and Nonconformist middle classes. More and more as the war progressed, they came to feel that the fate of reform at home was intimately bound up with the fate of the Union cause. If the South won, the upper classes, opposed to reform, would pronounce democratic government a failure and reform might be postponed indefinitely. Little wonder that Britishers followed the war with intense interest and that the government stepped warily in its American policy. What was true of the influence of American affairs in political considerations was scarcely less true in economic matters.

Mr. Pratt's survey covers too wide an area to have permitted very deep plowing. His chapters, therefore, seem to be more suggestive than definitive, but they indicate clearly that on the continent the division of opinion among the various classes on the American question was not much different from the division in Britain. There, too, reform agitation was in the air and economic factors exerted an important influence. The true liberals felt that the Lincoln government was fighting for the cause of democracy everywhere. Napoleon 111 in Paris and the Spanish authorities in Madrid watched Palmerston in London, but at the same time they were obliged to listen to liberal opinion at home. And it was not difficult to hear.

The writings of other scholars working in the Civil War field have taken the edge off some of the points made by Mr. Jordan and Mr. Pratt, but their book is nevertheless a useful one. The reader will find it a little "slow going" at times for neither author has a sprightly style. Theirs, is a book to be studied, not casually read.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

June 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

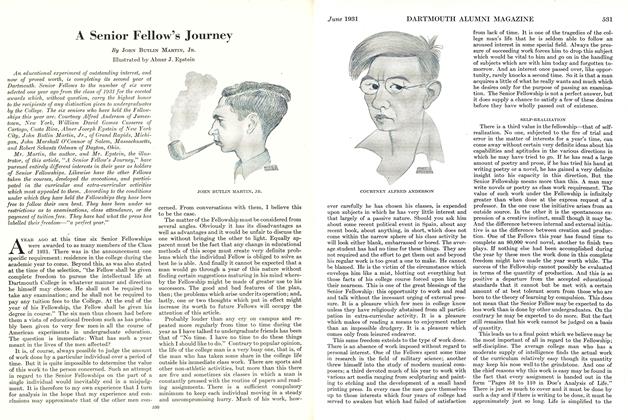

ArticleA Senior Fellow's Journey

June 1931 By John Butlin Martin, Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

June 1931 By F. W. Andres -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Expedition to the Island of Oesel

June 1931 By Wm. Patten -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

June 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1931

A. Howard Meneely

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE "DESERT RATS" MUSICAL SHORTHAND SYSTEM

December 1935 By D.E. Cobleigh '23 -

Books

BooksTHE ELECTRIC-LAMP INDUSTRY

December 1949 By H. L. Duncombe Jr. -

Books

BooksGENERAL EDUCATION IN THE PROGRESSIVE COLLEGE,

November 1943 By Irving E. Bender. -

Books

BooksNORTHWEST TO FORTUNE.

JANUARY 1959 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksJOYS AND SORROWS: REFLECTIONS

JULY 1970 By JON H. APPLETON -

Books

Books"One Man in His Time..."

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peter Smith