at the Baccalaureate Services in the Dartmouth College Chapel, June 14, 19S1

IN the few moments here which we give to retrospect of college years and to anticipation of years to come, I wish to emphasize what has been reiterated often, how little as a result of a college course one can assume himself possessed of learning in any complete measure. The maximum contribution of the college to the undergraduate can be hardly more than to point out the path which leads into the fields of knowledge and to define the spirit in which one must follow this path, if he is not to lose it.

Let us recall the Scriptural story of the blind man of Bethsaida. He sought Jesus in the hope of being healed. The Great Physician placed His hands upon him and dispelled his blindness and then asked him if he saw aught. The joyous but bewildered man, without acquaintanceship with perspective and with a sudden flood of new impressions rushing in upon him, could not grasp sense of proportion or form and replied, "I see men as trees, walking." The understanding Master then again placed His hands upon the man's eyes and asked him to look up, and the man's sight was wholly given to him and he saw every man, clearly.

The brief Biblical story, so simply told, may profitably be accepted as an allegory descriptive of the stages by which one seMuch cures mental sight. From time immemorial, among many peoples, the analogy of ignorance to blindness has been drawn. Our own literature has many a statement of this. A Chinese proverb reads, "The living man who does not learn is dark, dark, like one walking in the night." Frequently one hears the developing of intellect compared to dawning sight. In slightly different form, Coleridge in one of his essays has expressed a similar idea: "Ignorance seldom vaults into knowledge but passes into it through an intermediate state of obscurity, even as night into day through twilight."

of the agnosticism expressed at this season of the year in regard to the potentialities for public good of men transferring from college halls to the affairs of the outside world arises from an entire misconception of what the colleges believe themselves capable of doing, or of the extent to which college men hold themselves to have become finally possessed of an education. It is for us to recognize the fallacies in the attitudes ascribed to us. It is for us to correct these fallacies in our modesty as to the extent to which we claim we are possessed of knowledge. It is for us to declare our purpose to keep alive our aspirations for intellectual competence. Most of all it is for us to recognize that learning among human beings is a variable, in definitely capable of approaching a limit but incapable of ever reaching it.

The symbolism of progress by successive efforts ever for clearer vision is evidenced in the lives of any of the world's great scholars. Illustration of the spirit which drives men on unceasingly in open-minded search of learning is clearest shown in the scientific field. The preeminence of science in the world of thought in our time is not so much due to the intrinsic merits of the subject matter or even to its abounding interest as it is due to the qualities of mind which have been typical of its devotees. Study the lives of such men as Newton, Darwin, or Pasteur, and you find them slowly and painstakingly developing their theories, establishing elaborate series of cheeks and controls, withholding long from final conclusions, and, having arrived at such, still willing to amend them upon new evidence becoming available. The genuineness of effort always to focus their sight clearly on truth, the absence of arrogant selfsatisfaction in occasional glimpses of isolated facts, the indefatigable labor to avoid distorted views, the distrust of quick impressions, and the openminded willingness to observe new data,—these are the outstanding qualities which have characterized the really great men of science. These are the qualities which have captured the imagination of the world and won its confidence. Herein is to be found explanation of what we call the reign of science. When in the realms of theological, social, and political thinking the methods and the spirit for developing viewpoints are generally adopted that have marked the rise of scientific thought, then again these branches of learning will resume their rightful places with science as coequals in the field of learning.

Let us contemplate a single instance! On a February day, last winter, in a laboratory on Mount Wilson in California, the German scientist, Dr. Albert Einstein, sought corroboration of his carefully formulated theory of the shape of the universe. There he studied data furnished to him by Dr. Edwin C. Hubble and Dr. Walter S. Adams, discoverers of the "red shift" of island universes receding from the earth. After a time he turned to the representative of the Associated Press, and said, "This shift of distant nebulae has smashed my old construction like a hammer blow. The red shift is still a mystery."

I have taken this account from the NewYork World, in the editorial columns of which the brilliant "Mr. Lippmann soliloquizes:

"If we stop for a moment to remember the bitterness and the intolerance with which men have quarreled over questions of faith for centuries on end, the quiet remark of Dr. Einstein seems suddenly dramatic. Men have been exiled by their nations, excommunicated by their churches and condemned to death or prison by their peers for daring to believe that the earth was round or the sun a star or the heavens to be millions of years older than the first sign of life upon our own small planet. Dr. Einstein reconstructs his theory of the universe on a February day in 1931; and so free from its old shackles is science in the modern world that it occurs to no one to challenge his right to picture the universe as he pleases."

If the influence of the cultural college has been made effectively pervasive within its halls, among its graduates may be expected understanding of the fact that sharpened vision must be sought throughout the years of a man's life, that no points of view can legitimately hold as against new evidence which alters these, and that progress towards truth is dependent on life-long and persistent effort in which courageous thinking and clear seeing are of equal consequence. There are among the universes of religious and of social and of political thought "red shifts" which remain a mystery. Observations of any one of these may well smash the world's construction of theory like a hammer blow.

Even in a phrase so commonly used and of such apparent simplicity as "the fatherhood of God" a shift in significance can be demonstrated by the different interpretations placed on parenthood through so brief a period of time as that represented in the transition from the patriarchal family of old or from the feudal head of the baronial family of mediaeval times or even from the status of the father" in the Puritan home, to the conception of fatherhood in American life today. Likewise, in contemporary life the phrase has little in common denominators of meaning as between the Orient and the Occident.

So, likewise, in the sphere of social relations there are mysterious and baffling shifts, cumulatively operative, that must of necessity catch the attention of sharpened vision of the mental eye and breakdown constructions which we have formerly placed on the meanings of words like democracy and aristocracy, free will and determinism, individualism and collectivism, and a host of others. Are we in our antagonism to such words as aristocracy, and privilege, and control, to argue that some men are not more entitled to respect than others, or that some men are not more qualified to be given authority? In a world rapidly becoming overcrowded are we to leave the necessity of reduction of population to the natural elements as in starvation, or to the acquisitiveness of aggressive peoples as in war, or to the murderous irresponsibilities and antagonisms fostered by continual and prolific breeding of the mentally deficient or the physically unfit?

So again, in political organization, are we to accept the hazards of committing ourselves to working hypotheses, useful in previous times, but as archaic in the modern world as would be belief that the earth is flat and stationary? The old-time shibboleths require revision, if for no other reason than that the Ephraimites have learned to pronounce their h's. The scope of meaning of such words as nationalism, patriotism, and loyalty requires that the mind's eye grasp their whole dimensions if they are to be serviceable to future generations and to carry the connotations of high merit in relation to new environments which have been theirs in the past.

In short, wherever we turn we find that the shifting mass of conditions which attach to external life and the tremendously increased acquisitions of knowledge make any static condition of mind analogous to blindness when consideration is necessary of a world governed from day to day by ceaselessly changing sets of circumstances. What then in terms of our allegory are the succeeding steps to be taken to acquire sight?

First, we must recognize that men enter upon life without intellectual, spiritual, or social sight. The first necessity, therefore, is to realize blindness.

Second, we must remember that dawning vision rarely gives full sight at once. It is likely to give simply a suggestion of objects in which men and motives and social conventions and great causes are seen as trees, walking.

Third, it is to be recognized that this distorted vision is a step in the process of gaining clear sight. It is neither to be feared nor condemned except as one undergoing it seems about to become satisfied with it and to accept it as final.

Fourth, as neither the Divine Teacher nor the man blind from birth was willing to cease effort until clear sight was restored, so continuity of effort is necessary for understanding the great issues of life and for getting by the stage where men are seen as trees, walking.

It is with full recognition of the necessity of gaining sight, which shall make us capable of seeing solutions of new problems in our modern world, that consideration is to be given to the "men as trees, walking" stage as inevitable in the process of gaining clear vision. This is the stage in the development of intellectual sight in which many a college man is likely to find himself on graduation day. College life is unbalanced life, in that theory cannot be balanced by experience. Its thinking is developed without the checks of responsibility. Its speculations are unrestrained by conditions existent outside in the world of reality. Understood to be what it is, an intermediate stage in the process of gaining intellectual perception, the college education is invaluable. Misunderstood and accepted as final revelation of truth, it is either futile or dangerous.

The simile of Lord Macaulay is worth keeping in mind, wherein he discusses in terms of a sailing ship the qualities making for progress and stability: overburdened with ballast, it cannot move; overequipped with sail, it will founder. The making of any port is dependent upon due attention to both sail and ballast. Following out this imagery, there are those who in impatience at nonprogressive stability believe it somehow to be a useful as well as a dramatic adventure wholly to ignore the indispensable aspects of some degree of stability and who seek useless martyrdom by crowding on sail until shipwreck is inevitable. These forget that the derelicts they create may become menaces in the sea of life to intelligently navigated vessels journeying steadily towards some desirable port. It is not thinking based on a desire for theatrical effects that ought to be found among graduates of the cultural college. It is not such thinking that makes for social good.

The analogy of sight of the physical eye to capacity for mental vision can be followed indefinitely. In search for concepts of truth as well as in looking for the delineation of physical objects, it makes great difference whether we are looking for specific objects or for all that may be observable.

If we are to look simply for weakness, we may fail to see compensating strength, even greater. If we look simply for opportunities to destroy, we may miss far more valuable opportunities to substantiate or to rehabilitate.

Take the case of Jurgen, who was looking for release from belief, and told the God of his grandmother, "I cannot quite believe in you, and your doings as they are recorded I find incorherent and a little droll." Even Jurgen's sight catches more than that though he will not long forego his search for illusion. He adds, "Yet I am not as those who would come peering at you reasonably. I, Jurgen, see you only through a mist of tears. For you were loved by those whom I loved greatly very long ago: and when I look at you it is your worshippers and the dear believers of old that I remember. And it seems to me that dates and manuscripts and the opinions of learned persons are very trifling things beside what I remember, and what I envy!" And then, the God in whom he did not believe having vanished from his sight, Jurgen ascended the throne of Heaven and found his heart as lead within him and he felt old and very tired, "For," he said, "I do not know what thing it is that I desire! And this book and this sceptre and this throne avail me nothing at all, and nothing can ever avail me: for I am Jurgen who seeks he knows not what."

Here we have vividly portrayed the futility of disregarding visible values, for the sake of arguing that they are nonexistent; the maundering of a soul which ended its career with a shrug and the query, "Well, and what could I be expected to do about it?"

But the most hopeless individual in modern life is the man who thinks that goodness and intelligence and desirable influence are exclusively restricted to those who hold like opinions with himself. Him we may dismiss as irretrievably blind without pausing to discuss.

Many others, however, who are blind from preconceived opinions, hereditary instincts, influence of environments, and impulses of self-interest, have become ill at ease and discontented in suspicion of their limitations. These, impelled by actual desire to know the world outside themselves, strive to look over the barriers which encompass them. Dawning vision for them, however, does not at first give full sight but they too see men as trees, walking. Having believed everything all right, they jump to the opposite extreme of believing everything all wrong. What has before been their instinctive impulse to accept everything in the world as it has been found is transformed to a determination to reject all established things. Defects in the present organization of society and in all of its institutions are held to demand total extinction and a completely new beginning in the organization of human affairs. The Church is adjudged all wrong because it is not all right; colleges are held to be total failures because not complete successes; democracy is charged with being inevitably weak because not always strong; the established social order is held to be wholly corrupt because far from being completely virtuous: whereas, clearer vision would reveal that the Church is to unprecedented degree stripping itself of Pharisaisms and hypocrisy and looking back to the fundamental principles of Christianity; colleges, at home and abroad, were never so effective in serving their own generation; democracy was never more pervasive and more genuine; and the social order moves steadily, if slowly, away from coarseness, brutality, and cruelty into an atmosphere of greater kindness, fairness, and justice than the world has ever known before. It is a reasonable rule that we measure progress by the distance covered from our starting point rather than by the length of road remaining to be traversed.

Let us also not forget, furthermore, that the "men as trees, walking" stage is long advance from a state of blindness which we did not recognize. Let us, on the other hand, beware lest in satisfaction at having gained some measure of sight, we accept belief that we are seeing all. As in state of original blindness, so with partial sight always we may lift our eyes in expectancy of receiving the divine touch through which we may come to vision more full and to revelation more clear.

The President's Valedictoryto the Class of 1931

It is a legend of Spain that in the olden times, when the Moors went into exile from Granada, men locked the castles that had been their homes and carried their keys with them into far lands, waiting and watching for the time when they could return. Thus the years passed and the mansions in Granada decayed or were destroyed, and all that remained was here and there a key in some ancient family, significant of the former gloiy of its estate.

In a few hours you go out from what has been to you in common companionship a home, as it has been to thousands of men before you. But for you no key is necessary as patent of the associations which have been yours. The analogy as you hark back in memory will not be to the crumbling walls of of a mediaeval castle whose interior chills, but rather it will be to a great colonial house of cheer where for you entrance is to be gained but by lifting the latch and where within welcome and hospitality await you. The structure that you have known may be remodeled to meet changing needs but the wholesomeness and the joyousness of the life within will be the same.

To you as undergraduates, the age of the College has been an inalienable right. To you as alumni will belong the spirit of its eternal and glorious youth. For all of us the look backward through Dartmouth's years of life brings pride. For all of us the look forward brings responsibility. What the College has been other men have made it. What it shall be depends on us.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

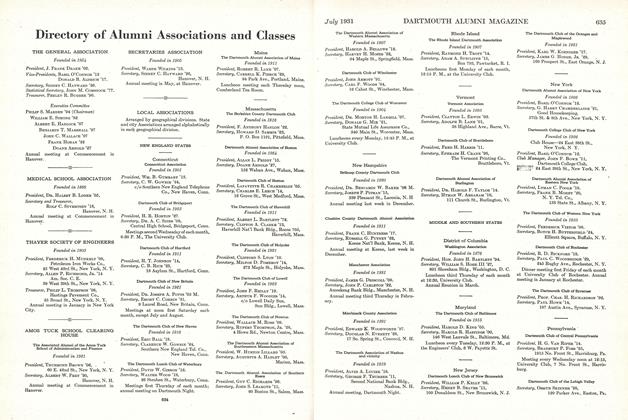

ArticleLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

July 1931 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926 in the Hills: The Glorious Fifth

July 1931 By J. Branton Wallace -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921 Tenth Reunion

July 1931 By Herrick Brown -

Article

ArticleCharacterizations of Honorary Degree Recipients

July 1931 -

Class Notes

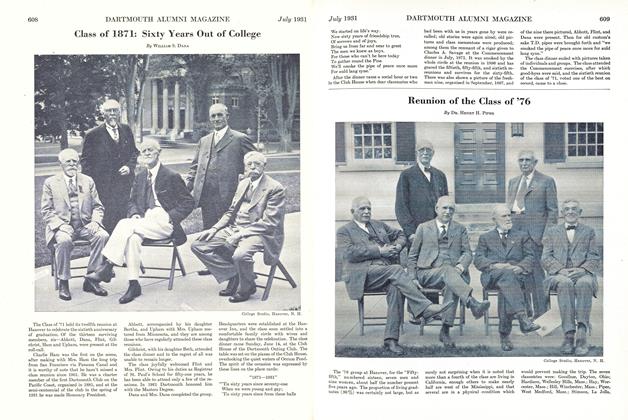

Class NotesReunion of the Class of '76

July 1931 By Dr. Henry H. Piper -

Class Notes

Class NotesTwenty-Fifth Reunion of the Class of 1906

July 1931 By Francis L. Childs

President Ernest Martin Hopkins

Article

-

Article

ArticleValedictory to Class of 1940

July 1940 -

Article

ArticleWashington

April 1943 -

Article

ArticleUndergrad interns: "Student's eye view"

OCTOBER 1985 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1954 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

November 1946 By John H. Minnich '29 -

Article

ArticleOPEN SESAME

OCTOBER 1991 By Professor Carol Bardenstein