Address at the Opening of Dartmouth College September 18, 1924

On occasion of a former address, in this place, at the opening of College, editorial comment in one of the metropolitan newspapers began with these words, "Speaking, as is custom, over the heads of the undergraduates to the outside public." Today I would not more deny the intent then ascribed to me than dispute the assumed incapacity of undergraduates to understand that which can be understood by the so-called outside public. The question in regard to college men is less frequently in regard to their abilities than in regard to their disposition to utilize these.

However, I hark back to this reference only because I wish to assert that my thought now as I speak is of you men of this college, and for the time I have only incidental interest in any others. The day is one specifically for consideration of your affairs. For some of you it is the beginning of life under new circumstances and in changed surroundings. For all of you it is the beginning of a new period of effort, a new opportunity of accomplishment. May the weeks and months to come be a time of advantage, of satisfaction, and of happiness to you all!

Words befitting the great traditions of academic life are so easily spoken and worthy deeds are so hardly done that I sometimes query whether there is any close relationship between them. Certainly words are no substitute for action, whether among those officially connected with the College or among undergraduates. Possibly some words may be incentives to action. It is in hope of the latter, presumably, that so many are uttered. I do not say this in any spirit of philosophical meditation, but with definite desire to recognize and to acknowledge a weakness common among all the groups which collectively make up the College. Nowhere, I believe,—not even in politics,—is there a greater disposition than in academic life to believe a highminded purpose to have been largely effected if it has been well phrased. Two baneful consequences result; first, that interest and energy tend to shift to other subjects, immediately utterance upon one is deemed felicitous; and second, that a spirit of smugness and self complacency arise from contemplation of a bespoken desire for excellence, even without the achievement of any corresponding degree of merit.

I ask you, therefore, to seek knowledge of the College primarily in its history, in its accomplishment, and, most of all, in its obvious opportunity, and to let my words or those of any other serve but as a suggestion for your own thinking, that you may reflect and consider and reach conclusion upon the function and the obligation of this historic college.

Charles Kingsley makes his Raphael Aben-Ezra inquire, in effect, "Is it not possible that we have been so busy discussing what the philosopher should be that we have forgotten that he must, first of all, be a man?" Sometimes it seems not improbable, in our discussions of scholarship, and of the bearing of scholarship upon intellectual power, that we may forget that our scholar must first of all be a man. If I believed that a real spirit of tolerance made eventually for the defeat of positive conviction; if I believed that true knowledge made at the last for negation, passivity or cynicism ; if I believed that the finest intellectual attainments were incompatible with the virility and strength of manhood, interpreted in terms of body and soul as well as of mind,—if I believed these things, I would not believe in the ideals which pertain to the American college, and I would ask no other man to believe in them.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, in his great essay on "The American Scholar," states that in our functionalized form of society, by which man gives himself to a specialized task, manhood tends to be ignored and lost; and he argues that the individual, to possess himself, must sometimes return from his own labor to embrace all the labors of other men. He continues, "The planter, who is Man sent out into the field to gather food, is seldom cheered by an idea of the true dignity of his ministry. He sees his bushel and his cart, and nothing beyond, and sinks into the farmer, instead of Man on the farm. The tradesman scarcely ever gives an ideal worth to his work, but is ridden by the routine of his craft, and the soul is subject to dollars. The priest becomes a form; the attorney a statute book; the mechanic a machine; the sailor a rope of the ship.

"In this distribution of functions the scholar is the delegated intellect. In the right state he is Man Thinking. In the degenerate state, when the victim of society. he tends to become a mere thinker, or still worse, the parrot of other men's thinking.

"In this view of him, as Man Thinking, the theory of his office is contained. Him Nature solicits with all her placid, all her monitory pictures; him the past instructs; him the future invites."

This matter of the thinker versus the man thinking or the parrot of other men's thinking is one which requires constant attention in a community like ours, at any period of attempted acceleration in intellectual accomplishment. We all tend to think exclusively and we all tend to lose our perspective as we move our special interests closer to us within the foreground.

I have read the words of men who ridiculed as weak sentimentality the emotional affection which binds men to their own college, their own community, or their own country, and I have seen with concern the occasional undergraduate who parroted this thought. Among the mass of other data available, the expert testimony of leading psychiatrists in a recent criminal trial on the unnatural effect of suppressed emotions in youth gives some light on this point.

I have heard both without and within the college the argument that body-building and activities which make for the physical development of youth are no part of the college's legitimate sphere of action. But the loss to the world of the long list of incompleted lives of men of talent who died for lack of physical stamina to support their mental capacity is argument enugh on this without consideration of a wealth of other available facts.

I have considered the contentions of those who argue that to attempt to breed reverence for the spirit of religion is no part of the responsibility of the college, —and with this contention I have patience least of all!

In the first place, the college is a trust, consecrated to certain ends. It is the projected impulse of men of strong religious conviction who gave their thought, their labor and their lives that this agency for the perpetuation of an intelligent religious spirit might be made permanent and infectious.

In the second place, in my belief, a sense of personal and individual responsibility for making the world better, such as religion alone most completely gives, is an essential for any man who wishes to live a life worthy of the best within himself, or serviceable to those within the group of which he forms a part.

One man associated with others composes the group, and the constructive intelligence and the positive goodness of one man definitely affects the sum total of mental and spiritual attributes which pertain to the group. Upon those, therefore, who would make their lives significant there rests the obligation to supplement their own capabilities by effort for contact with the great motives of life which make for the betterment of mind and soul. Education without the influence of the spirit of religion is incomplete education. Goodness and truth spring most naturally from that humility which real religion gives.

Shall we not assume that the education here to be acquired is to have sufficient merit so that men responsive to it shall find accessible to themselves the influence of those great forces outside themselves which dominate right impulses and right actions! And if we grant the existence of such forces, shall we not grant an origin, and if we acknowledge this, have we not recognized the sovereignty of that incentive to be good which men have long incorporated within a belief which we call religion.

Is it that anything could be more restrictive or more stultifying in interpreting the purpose of intellectual development than that we should disregard individually or collectively that which is highest in the heavens and which is most fundamental on the earth; that which draws men always away from evil and that,which leads them ever towards the things which are true,—towards truth which is the spirit of goodness which is the spirit of God!

Another matter is to be emphasized. I believe that it will make for common understanding of many things if we start our work within this college with full recognition of the fact that all education is self-acquired. The acquisition of education is dependent on self-effort. The extent to which this self-effort can expect to be rewarded is in turn dependent on self-discipline and self-control.

The college provides facilities, environment, atmosphere, and influences within which self-education can be, for most men, more definitely and more largely effective than it could be without these. The college cannot, if it would, transmit education on platters of silver to those undesirous of accepting it or to those passively indifferent. The college can render valuable help and experienced direction to the efforts of those seeking help and desiring direction for acquiring an education.

I dwell upon this point for a moment because of tendencies in modern day discussion to argue that the process of education should be divorced from all that is exacting and all that is difficult. It can't be done! The first essential for gaining education is possessing or developing a trained mind, amenable to will and subject to purpose, delicate enough to respond to a gentle impulse and stalwart enough to function and endure under the whip and spur of special circumstance. These are not attributes of a realm to which, in college, we can be carried "on flowery beds of ease," while outside "others fight to win the prize or sail through bloody seas." Elbert Hubbard once said, in an address before the Dartmouth student body, that aspiration and perspiration were of about equal importance in securing the maximum advantages of a college education. Indeed, I would seriously submit for undergraduate consideration the question whether, from the point of view of their own ultimate good, there has not been a. too complete disappearance, from the college curriculum and from college life, of compulsion and of requirements, rigorous, and even irksome, if you will, which temper the mind and test the soul of men! The great reservation which an anxious world feels today in regard to college men is not in regard to their culture or their social polish but in regard to their stamina,—mental, moral and spiritual ! As the Apostle Paul, in obvious solicitude about the qualities of his attractive and talented young friend Timothy wrote, "Thou therefore endure hardness,''—so writes the older generation today to its youth !

In consideration of this point, I would, however, urge that we be nice in our interpretation of the word "hardness." It should not be confused with roughness nor with coarseness, which some seem to believe are necessary concomitants of strength. Let us not fall into the fallacy which Montague ascribes in his "A Hind Let Loose," to the citizens of Halland, whose word "jannock" enshrined their faith that to be a diamond you must be rough. Unfortunately, this is not alone a fallacy of the people of a hypothetical city in a work of modern fiction, but it is the conviction of many a man among the graduates of American colleges. The distinguished president of a great New England university has said that if he were to accept the opinions of some of his college friends in regard to what constitutes manhood he would be forced to the conclusion that no blood is red which passes through the brain. Surely, it is among college men in particular that we ought to be able to assume exemplification of the truth that strength is not incompatible with intelligence and that both are largely enhanced in worth when combined with sweetness of character and gentleness of demeanor.

When we come to attempt a detailed definition of the purpose of education we are forced to recognize that each generation has the right, and often has utilized it, to define this purpose in accordance with its needs. Likewise, a sense of humility is bred in attempting to define this purpose in any detail when some definitions of the past are examined. Perhaps the worst, in principles enunciated, was that of the ancient Dean of Christ Church who gave three reasons for the desirability of higher education:

First, that it enabled you to read the words of Scripture in the original tongue;

Second, that it entitled you to a sense of contempt for those who couldn't, and,

Third, that it qualified you for positions of large emolument.

Unquestionably we are on surest ground when we define the purpose of education to be knowledge of the truth. But if we attempt to be more specific, immediately we find ourselves in difficulty when we meet the age-old query which Pilate asked of Jesus, "What is truth?" Through long centuries the thought of the world has been led ever upward and progress has been made possible by the mental travail of inquiring minds of men who sought to make fragmentary truth more complete, while at the same time these men have suffered persecution, ostracism and death at the hands of men of timid mind who feared new knowledge and chose to hold that truth had become evident in all completeness at some previous time.

Mr. Rudyard Kipling, in his installation address as Rector of St. Andrews, last October, made interesting comment, in his inimitable way, on the continuing prevalence in the world of error and on the restricted area in proportion in which truth prevails. He cited the difficulties under which early man in competition with his rivals sustained his life by strategy, deceit and camouflage. He reached conclusion that the power of speech when first developed must have been accepted primarily as a new and powerful medium for perfecting these devices of untruth and making new misrepresentations, and then he continues:

"Imagine the wonder and delight of the First Liar in the World when he found that the first lie overwhelmingly outdid every effort of his old mud-and-grass camouflages with no expenditure of energy! Conceive his pride, his awestricken admiration of himself, when he saw that, by mere word of mouth, he could send his simpler companions shinning up trees in search of fruit that he knew was not there, and when they descended, empty and angry, he could persuade them that they, and not he, were in fault, and could dispatch them hopefully up another tree. Can you blame the creature for thinking himself a god? The only thing that kept him within bounds must have been the discovery that this miracle-working was not confined to himself.

"Now the amount of truth open to Mankind has always been limited. Substantially, it comes to no more than the axiom quoted by the Fool in TwelfthNight, on the authority of the witty Hermit of Prague: 'That that is, is.' Conversely, 'That that is not, isn't.' But it is just this truth that Man most bitterly resents being brought to his notice. He will do, suffer, and permit anything rather than acknowledge it. He desires that the waters which he has dug and canalized should run up hill by themselves when it suits him. He desires that the numerals which he has himself counted on his fingers and christened 'two and two' should make three and five according to his varying needs or moods. Why does he want this? Because subconsciously he still scales himself against his age-old companions, the beasts, who can only act lies. Man knows that, at any moment, he can tell a lie, which, for a while, will delay or divert the workings of cause and effect. Being an animal who is still learning to reason, he does not yet understand why, with a little more, or a little louder, lying, he should not be able permanently to break the chain of that law of cause and effect —the justice without the mercy— which he hates, and to have everything both ways in every relation of his life. In other words, we want to be independent of facts, for the younger we are the more intolerant we are of those who tell us that this is impossible."

But no adequate discussion of what constitutes truth, nor of the principles which underlie search for it, can be given within the limits of an occasion like this. Those are questions to the answering of which essentially the whole work of your college course may well be devoted,- and then you will but have made a beginning.

It appears, then, that for the practical purposes of a couple of thousand of undergraduates, eager to know at the mo- ment what the college conceives education to be, some suggestion of a problem is desirable, significant of an important sphere of action in which truth has not yet been found and wherein not even has the data been assembled from consideration of which truth may be discerned.

To me it seems that one of the fundamental purposes of higher education is that men shall learn how to live. To live is something quite different than to exist. Many a man exists long and lives scarcely at all. To live is to develop the capacity for understanding life and to acquire the ability for deriving satisfaction from it. The greater the understanding and the more complete the intelligent satisfaction, the more adequate is the living,—adequate for needful selfjustification, for genuine happiness, and for. real contentment.

To understand life and to seek genuine satisfaction from it is to accept responsibility and to meet the demands of responsibility. Vital among the factors which comprise responsibility is that which considers the needs of the lives of others and denies to no other man and to no other groups of men the opportunities essential for self-respect and selfsatisfaction. If for no nobler reason, this is essential as our contribution to a condition in which others shall not deny us like opportunities.

Mankind has never been entirely free from this obligation. It exists today, however, to a degree unprecedented in the history of the human race. The boundaries of the space within which men live has been so greatly compressed, and the formerly existent proscriptions of time necessary for contact among men have been so largely removed that such words as freedom and liberty become practically meaningless, except as as they be re-defined and become more inclusive. Freedom to disregard others and liberty to think only of self have become impossible now, regardless of whether they were ever desirable.

Education, then, has to do not only with our lives individually but with our lives collectively. Education, if it is to be justified, must help us to know better how to live together.

For a group, such as ours, which is known as a college it is interesting to remind ourselves that in the first instance the word "college" had reference to the conditions under which men lived together rather than to their specific reason for so being assembled. It is, likewise, not irrelevant in this connection to recall that the word "school" by derivation suggests leisure and by implication signifies not a time of idleness but rather a time of special privilege for acquiring benefits not likely to be available under the exactions of the busy-ness of later life.

How, then, shall we live together? There is no perfect practice. There is no universally accepted theory. There is but just beginning to be any widespread interest shown in the matter. Only recently has emphasis outside the church been placed on the imperative need of discovering and codifying the elementary principles by which men may live together, preserving for the good of all the effort of individual excellencies and avoiding for the good of all the domination of evil impulses.

No problem of life demands more accurate answer. No problem of life is more insistent upon prompt answer. Within its boundaries lie the securities that neither material wealth nor militarism, nor un-intelligent good will can give; within its scope are included the happiness which governments cannot insure ; within its solution lie the satisfactions that ignorance is powerless to protect.

This is your problem; how shall men live together! The question is emphatic and continuous,—challenging, begging, commanding solution by your generation as by no generation that ever lived. May you find this, the college of your choice, strong to supplement your strength.

Finally, as inspiring in themselves and as indicative that the study of this problem is not out of accord with what has been the spirit of higher education, I quote the words of Edward Caird, Master of Balliol after Jowett, addressed to the men of that old and great college:

"As members of this little society you have a great tradition to maintain—I do not mean of success in attaining university distinctions, though that no doubt is a good thing—but of participation in the highest aims of the intellectual and moral life of the nation. Among your predecessors there have been many—I can remember not a few myself—who began in this college to show that love of truth and freedom, that interest in the national welfare, that sympathy with the needs and cares of others, which afterwards enabled them to widen the bounds of knowledge, to raise the moral tone of professional life, to maintain the honour and justice of the nation in dealing with weaker and less civilized races, or to bring help and healing to the hardships and sufferings of the poor in our own country. And if it is the few who do great and marked service in any of these directions, we have to remember that it is the spirit of the many that makes their efforts possible.

"A man who has once lived in a society where the moral and intellectual tone was high, has by that very fact had his courage raised to attempt things of which he otherwise would never have dreamed. And all the members of such a society—especially when it is so small as a college—the least as well as the most notable, must contribute powerfully to help or to hinder the maintenance of that generous community of life, that fellowship of friends, of which Aristotle speaks, that free sympathy of those who have no aims of which they need be ashamed, in which all that is healthy and strong, all that is good and true in the character and minds of individuals, is sure to grow and ripen.

"May it be yours in the future to look back on your college days as a time of faithful and persistent effort to develop the powers which God has given you; a time of free and brotherly fellowship, of growing strength of mind and character, darkened by no remembrance of lost opportunity, or of any action unworthy of a gentleman and a Christian."

Doctor Nichols and Professor Einstein at Nela Park This picture is of especial interest to Dartmouth men as it was one of the last taken of Dr. Nicnols and shows him at the entrance to the laboratory where he was so actively and successfully occupied at the time of his death.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE ALUMNI FUND

November 1924 By Clarence G. McDavitt 1900 -

Article

ArticleHaving but recently welcomed to the ranks

November 1924 -

Sports

SportsATHLETICS

November 1924 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1924 -

Article

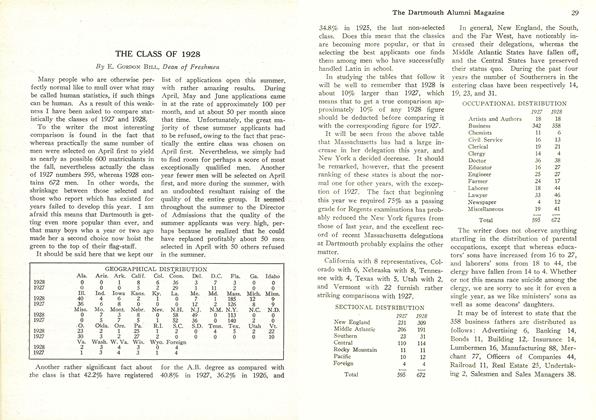

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1928

November 1924 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1917

November 1924 By Ralph Sanborn

President Ernest Martin Hopkins

Article

-

Article

ArticleTUCKER SCHOLARSHIPS AWARDED

-

Article

ArticleCurtis Is Nominated As Alumni Trustee

March 1954 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Names on the Moon

MARCH 1971 By ALLEN L. KING -

Article

ArticleYou're a V.I.P.* To the A.R.O.

January 1949 By CHARLOTTE E. FORD -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Club of the Year

JUNE 1972 By H. FLINT RANNEY '56 -

Article

ArticleTHE AMOS TUCK SCHOOL

APRIL 1906 By Harlow S.