Professor of Public Utility Management, Graduate School ofBusiness Administration, Harvard University

This paper by Professor Ames appears, on careful reading, to suggest the necessity of reform in an established institution, namely, the system of capitalism which lies at the foundation of the business structure of this country. Capitalism, as we have it here and now, seems to have been the child of the Protestant Reformation,5 reared and educated by a succession of great thinkers on political economy and economics beginning with the classical economists, Adam Smith, Ricardo and Mill. These men and their successors built up an institution like an established Church with a complete theology and a creed which has been taught in our schools and colleges for a century.

The economists began by restricting their field of inquiry to man's material wants and desires and were thereby enabled to see them-so clearly that generalizations about production, markets, money and other economic activities which were of extraordinary value were made possible. It is not perhaps too much to say that the great industrial era, of which we are the heirs, owes much of its success to the men who invented this methodology and produced these generalizations. They are set forth for us in the standard text books on economic theory, still used in our colleges, and are the basis on which the average business man thinks and the average legislator legislates about business matters. But these men are not economists in any proper sense of the word. They have learned their economics as they learned their religion in Sunday school.

The difficulty with this kind of elementary teaching is that it does not give due importance to change. At the time when the economic catechism which these men have learned was written change was so slow that it could safely be disregarded; and it was. But the acceleration between that time and the present day has been so great that the man, or the institution, which now disregards change, does so at his peril.

Recognition of change, and adjustment to it, is very difficult for institutions, or great systems of thought, like the Church, so that we commonly find them lagging far behind the current thought and practice of our day. There are a small group of vigorous preachers so far in advance of their Church that they hardly maintain contact with it. These might be likened to the "leaven hid in three measures of meal."

Our orthodox system of economic thought is in a position very similar to the Church. A state of balance, or equilibrium, seems to be the normal condition of all parts of the world in which we live, and this being the case the economists showed wisdom by incorporating this principle into their system. But when such a balance is struck in the economic field in utter disregard of its effect on other phases of man's life, It may not be worth the price. Under the relatively static conditions of a century ago the separation of man's material wants and desires from all other phases of his life was useful for purposes of study, and the practical exclusion of all other phases did not produce too serious a distortion. But now the ruthless use of economic power to restore equilibrium in that field is so shocking to our social sense that the economist in spite of himself must count the cost. In short, the other phases of man's life can no longer be disregarded in framing sound economic judgments. Determinism in economics, as in theology, can go too far.

As in the Church, so here, we have a small band of vigorous men who are in contact with reality and aware of the changes that have occurred but they have not yet attained a position of sufficient power to make radical reforms in the teaching of the Sunday schools, so to speak. As a result business men, so far as they use economic theory at all, follow the teachings of the orthodox school. Who can blame them ?

The authorities seem to agree that this depression is fundamentally like those that have preceded it for the last hundred years or more; that we shall recover from it as we have before and that a period of prosperity is ahead of us. This prediction about prosperity can only be fulfilled provided the conditions of the world in which we now live are substantially the same as they were when the economic laws which we are trying to use were formulated. If there has been any radical change in the conditions, the old laws will not work satisfactorily. We all know that the conditions have changed.

Economic theory properly assumes equilibrium to be the normal condition of man's life and it indicates the ways in which equilibrium is restored when it has been upset by some outside disturbing cause. But if, as often happens, these outside causes arise in some other sphere of man's activity, they are beyond the scope of economic theory, and therefore mere marauders to be driven off by the police. This, as will later appear, is a false principle. Under modern conditions the other phases of man's life cannot be excluded. While admitting that the school of orthodox economic theory has earned the great reputation which it has enjoyed, we suggest that it has outlived its usefulness as a guide to action because, being designed to operate under conditions which were essentially static, it deals only with a part of the life of man—his material life—and not with his life as a whole.

The reason for the great usefulness of economic theory in the past is suggested by Dr. Whitehead when he says: "Apart from the capital of abstract ideas which had accumulated slowly during two thousand years, our modern life would have been impossible," and he gives as examples—mathematics—the abstract theory of music—the abstract theory of political economy—and the abstract theory of the currency. He then adds: "The point is that the development of abstract theory precedes the understanding of fact. The instance of political economy illustrates another important point. We all know that abstract political economy has in recent years been some- what under a cloud. It deals with men under an abstraction; it limits its view to the 'economic man.' It also makes assumptions as to markets and competition which neglect many important factors. We have here an example of the necessity of transcending a given morphological scheme. Up to a point the scheme is invaluable. It clarifies thought, it suggests observation, it explains fact, feut there is a strict limit to the utility of any finite scheme. If the scheme be pressed beyond its proper scope, definite error results. The art of the speculative Reason consists quite as much in the transcendence of schemes as in their utilization."6

We appear to have reached the point where the speculative Reason must intervene to transcend the old schemes of economic theory. This is what Professor Ames has done for us in his paper on "Progress and Prosperity." He has made a very suggestive sketch of an economic philosophy without entering the field of economic theory or methodology.

In the course of more than a century the theoretical economists have worked out a system of abstract ideas which have been of immense value in helping us to gather and to understand our economic facts, but under the changed conditions of the present time the economic laws which these men have formulated are by no means a safe guide because the scope of the method employed was too narrow.

On this point the following quotation from Dr. Whitehead is pertinent, though it refers specifically to physiologists. "As a question of scientific methodology there can be no doubt that the scientists have been right. But we have to discriminate between the weight to be given to scientific opinion in the selection of its methods, and its trustworthiness in formulating judgments of the understanding. The slightest scrutiny of the history of natural science shows that current scientific opinion is nearly infallible in the former case, and is invariably wrong in the latter case. The man with a method good for purposes of his dominant interests, is a pathological case in respect to his wider judgment on the coordination of this method with a more complete experience. Priests and scientists, statesmen and men of business, philosophers and mathe- maticians, are all alike in this respect. We all start by being empiricists. But our empiricism is confined within our immediate interests. The more clearly we grasp the intellectual analysis of a way of regulating procedure for the sake of those interests, the more decidedly we reject the inclusion of evidence which refuses to be immediately harmonized with the method before us. Some of the major disasters of mankind have been produced by the narrowness of men with a good methodology."7

It would appear that our economic theorists stand in much the position which Dr. Whitehead describes and both we and they should heed his warning. It has been suggested that the scope of their method is too narrow; that it has done its work within this field, and that it should be superseded by a new method with a wider scope. On this point Dr. Whitehead says: "The main evidence that a methodology is worn out comes when progress within it no longer deals with main issues. There is a final epoch of endless wrangling over minor questions." (Read any of the economic journals for examples of this.)

"Each methodology has its own life history. It starts as a dodge facilitating the accomplishment of some nascent urge of life. In its prime, it represents some wide coordination of thought and action whereby this urge expresses itself as a major satisfaction of existence. Finally it enters upon the lassitude of old age, its second childhood. The larger contrasts attainable within the scope of the method have been explored and familiarized. The satisfaction from repetition has faded away. Life then faces the last alternatives in which its fate depends.

"These last alternatives arise from the character of the three-fold urge which I have already mentioned: To live, to live well, to live better. The birth of a methodology is in its essence the discovery of a dodge to live. In its prime it satisfies the immediate conditions for the good life. But the good life is unstable; the law of fatigue is inexorable. When any methodology of life has exhausted the novelties within its scope and played upon them up to the incoming of fatigue, one final decision determines the fate of a species. It can stabilize itself, and relapse so as to live; or it can shake itself free, and enter upon the adventure of living better.

"In the latter event, the species seizes upon one of the nascent methodologies concealed in the welter of miscellaneous experience beyond the scope of the old dominant way. If the choice be happy, evolution has taken an upward trend; if unhappy, the oblivion of time covers the vestiges of a vanished race."8

Could any generalization of a philosopher more accurately describe the position in which we now stand? We are literally at the parting of the ways. Unless we can find a new methodology making possible new and wider generalizations in regard to our social and industrial life, our progress may be at an end. We shall rise in time out of severe depression, but we shall not attain a true prosperity. The way in which this may be accomplished is suggested by the following quotation from Dr. Whitehead: "The enormous advance in the technology of the last hundred and fifty years arises from the fact that the speculative and the practical Reason have at last made contact. The speculative Reason has lent its theoretic activity, and the practical Reason has lent its methodologies for dealing with the various types of facts. Both functions of Reason have gained in power. The speculative Reason has acquired content, that is to say, material for its theoretic activity to work upon, and the methodic Reason has acquired theoretic insight transcending its immediate limits. We should be on the threshold of an advance in all the values of human life.

"But such optimism requires qualification. The dawn of brilliant epochs is shadowed by the massive obscurantism of human nature. Obscurantism is the inertial resistance of the practical Reason, with its millions of years behind it, to the interference with its fixed methods arising from recent habits of speculation. This obscurantism is rooted in human nature more deeply than any particular subject of interest. It is just as strong among the men of science as among the clergy, and among professional men and business men as among the other classes. Obscurantism is the refusal to speculate freely on the limitations of traditional methods. It is more than that: it is the negation of the importance of such speculation, the insistence on incidental dangers. A few generations ago the clergy, or to speak more accurately, large sections of the clergy, were the standing examples of obscurantism. To-day their place has been taken by scientists. . . . The obscurantists of any generation are in the main constituted by the greater part of the practitioners of the dominant methodology. Today scientific methods are dominant, and scientists are the obscurantists."9

As usual we find the philosopher and the idealist the most practical of men. Here we have, stated in a paragraph, the opportunity and the hazard of our day.

In the foregoing we have suggested some reasons for challenging the soundness of the economic methodology which has been our guide in the production and distribution of wealth. The evidence that we are losing confidence in classic economic theory seems clear. If we were not, the doubts which we hear expressed on every hand as to the success of the capitalist system would have no meaning. Heretofore such doubts have been confined to socialists and radicals; now they are coming from the capitalists themselves.

Our practical business men know, for example, that the so-called law of supply and demand, as explained in the standard books on economics, works about like the Volstead Act; that the law of monopoly profit went into the discard years ago; and that the law of diminishing returns is, for the business man with science as his tool, merely the law of diminishing brains. The list might be extended, but it is needless.

These are hopeful signs, for the massive obscurantism described by Dr. Whitehead may be overcome if the business and professional classes, aided by the more alert of the economists, are prepared to listen to new ideas. But even if our economic methodology is out of date, that does not prove, or even suggest, that the economic philosophy which Professor Ames sketches will help us. Socialists, communists, and other radicals, have been predicting the downfall of capitalism for two generations, and suggesting new schemes.

New visions must be both true and timely, for even the truth may prove sterile unless it comes at the right time. But those who examine Professor Ames' paper with an attentive eye will perceive that it has come straight as an arrow to the point where it was wanted. Obviously, the old capitalist system has developed vices which must be corrected or they will destroy it; less obvious, but not less true, is the fact that both socialism and communism have seen their best days. What we needed was a new philosophy of capitalism socialized so as to fit the conditions of the present day. We have it here. Professor Ames has seen the "star in the East."

If this high hope is to be realized, the Ames philosophy must open the way for a new methodology which will make possible new and wider generalizations which were excluded by the old one. This raises the question: what are the essential differences between Ames and the concepts of the orthodox economists?

At the outset of "his mad career" he boldly, or perhaps inadvertently, discards the division of man's activities on which the dominant economic system is based. He refuses the concept of the "economic man" because he knows that man does not live by bread alone. The old concept was what Dr. Whitehead refers to as a "dodge" on which the whole methodology was based and which in its prime made possible such important generalizations. But "the law of fatigue is inexorable," and if this concept is not replaced by a new one, we face the situation which Dr. Whitehead has described. The weakness of the old concept is that it seeks to divide the indivisible. Man is an organic whole which cannot be divided without destroying the principle of life, and there is reason to believe that the time has passed when his economic activities can safely be studied in isolation. By abandoning this concept and putting in its place the concept of the whole man, Ames has, at a stroke, removed the main obstacle in the path of progress. That this widening of the field is beset with danger cannot be denied. Yet the mere fact that it has its dangers is no reason for ignoring a real problem. "Even if heads be weak, the problem remains."10

His concept of man as an organic whole is founded on his philosophy of the nature of man's life as a process of change or becoming. This doctrine is very old but the form given to it in our own day by Dr. Whitehead is the one upon which Ames relies. This is a death blow to the fundamental concept in the dominant economic system. By excluding all but the economic aspects of man's life, change becomes "a random element" which tends to destroy the equilibrium at which the system aims, and if maintained, might involve some major injury to his life as a whole. Under the relatively static conditions which this methodology sought to explain, this narrowing of the field might do no great harm. But if man is a creature demanding continuous advance, equilibrium maintained in one field at the expense of another involves great danger, and a system which tries to produce such equilibrium is based upon a false principle.

We may thank God that Ames is one of those rare men who has been able to keep his head free from concepts which prevent most of us from seeing the obvious. He must be prepared to face the "massive obscurantism" to which Dr. Whitehead refers, but fortunately there is a very large group of people who are already suspicious of the dominant method. To them it may be worthwhile to suggest some of the new generalizations which might be reached if Professor Ames' philosophy were generally accepted.

Consider, for example, the problem of unemployment which now plagues us so sorely. The old method stood helpless before it. Improved technology, by increasing the productive power of labor, inevitably throws men out of work. A gradually increasing demand will tend to mitigate this evil, but both capitalists and labor unionists are so impressed by it that they are advocating the five-day week. This method results in increased idleness, or leisure, the use of which is beyond the scope of the old methodology, for with education and the profitable use of leisure the old system of economics has nothing to do.

But the Ames method opens the way to the solution of the problem; in fact, it does not appear to him to be a dilemma at all. He says: "Unemployment in the present economic depression, due to the labor-saving improvements in those activities that produce consumables,11 instead of being a calamity, should in fact be a blessing, a condition which our mechanistic age has been striving to bring about. There has been released a large amount of labor which can be used, not only to provide non-necessities, but also non-consumables, both tangible and intangible,ll which are indispensable to the advance of civilization. A superman above the earth would be delighted with the opportunity. He would have no question but that it was an opportunity. He would only be worried for fear he might not make the best of his opportunity by failing to allocate the surplus labor to those activities that would most speedily advance civilization."

Thus, the broader scope of the Ames philosophy turns a curse into a blessing, and opens the way to a complete harmonizing of the claims of labor and capital.

Of course, the success of this method implies the existence of new wants or desires to be supplied. These are implied in his fundamental assumption that man is a growing organism. This may be a naive assumption, but let us see. There appear to be many who believe that we cannot expect the changes of the next twenty years to equal those of the last. Such a proposition must rest on the assumption that the rate of acceleration which has been increasing for centuries, and which Henry Adams estimated was doubling every ten years, has suddenly turned in the opposite direction. This can hardly be true. What is more probable is that, under the shadow of the dominant method, the evidences of coming change have escaped the eager gaze of those who were not looking for them. Change has not been accepted by econo mists as the foundation of their theory and has not been planned for. Under the Ames method such planning for new inventions would be a prime objective. If the conditions which have governed our past continue, the changes in the next twenty years should be four times as great as in the last twenty, and such a presumption is sustained by the progress of science which is the main cause of acceleration.

The discoveries of science in the last twenty years have been amazing, and yet the great scientist is the humblest man in our world. He is constantly proclaiming his ignorance ; saying that he has just opened the door and stands on the threshold of new discoveries.

We may conclude, therefore, that we shall not lack new inventions and discoveries. It is far more likely that we shall be overrun with them, and that our real problem is one of control and regulation.

But where shall we get the money to pay for these new things? (I have actually been asked this question.) The answer is simple. Just where we got the money for the things we now have.

In the recent past we have invested too large a proportion of our capital in the production of "consumable tangibles"11 with the result that huge sums had to be spent on advertising and selling goods which the consumers didn't really want. If the sums spent in forcing these goods upon the market had been spent on inventing and making things that people did want, real progress would have been made and our present depressed condition alleviated. This is only a minor source of capital to supply new wants, but it might amount to a billion or so each year.

So far as the new inventions take the form of devices which save time or increase the productiveness of labor (provide us with more slaves to work for us, as Ames puts it) they pay for themselves, as they have done in the past. Take the telephone, for example. The time saved by its use in this country during the last ten years, if put to productive use, would have provided the five billion or more of capital invested in this industry in a fraction of the time; and the nation has had the balance as its profit.

So far as the new inventions are in the form of "non-consumable tangibles or intangibles"11 which do not result in an immediate saving of time or labor, such as new methods of education, parks, works of art, or advances in medical science, they will be paid for out of the profits of the new inventions above referred to. These profits have been immense during the last generation, as evidenced by the increase of our national wealth, and, unless we mismanage our affairs shockingly, they bid fair to be even greater in the future.

This brings us to another important generalization made possible by the Ames method. As he points out "the economicwealth of a people is evidenced by the proportion of its labor that is engaged in non-consumable tangibles and its civilization is evidenced by the proportion of its labor that is engaged in non-consumable intangibles." This idea in itself is not new, but it is new in the field of economics. The whole field of non-consumable intangibles as conceived by Ames was excluded by the old methodology, although it undeniably includes the most important of all human activities. With this field now open to us we may consider methods of diverting capital into it. The capital must come in the first instance out of profits earned in other fields and may be derived either from voluntary investments of private capital, like the endowment of universities, research foundations and art museums, and the purchase of works of art, or from taxation for public education, parks, museums, etc. The amounts spent in these and similar ways are the measure of our civilization and, if this point were once clearly grasped, the rate of flow of capital into this field would be greatly accelerated. We now resist high taxation, mainly because this point is not grasped. If we saw the rate of taxation as a measure of civilization, our views might change. The fault lies at the door of an outworn methodology which excluded from consideration the non-consumable intangibles and some of the tangibles.

Another important result which might follow the general acceptance of Professor Ames' economic philosophy would be to reduce the danger of international war. The chief characteristic of his philosophy is the change of emphasis on the various forms of activity which constitute man's life. The old economic system placed major emphasis on "the struggle for existence," so that freedom of competition or industrial warfare was its outstanding feature. Owing to a methodology which was too narrow, too much emphasis was placed upon the production of consumable goods and the result was that too much capital went into this field. The natural result was overproduction which led inevitably to competition for foreign markets. The consequence has been recurrent international wars, which now threaten the destruction of civilization itself. The new emphasis on change, invention and science which Ames suggests would almost certainly mitigate competitive warfare and the struggle for foreign markets.

Professor Ames did not attempt to outline a new economic methodology, and all that this paper aims to do is to suggest some of the new generalizations which such a methodology might produce. Two have been suggested. Here is a third.

The fields of economics and of government are intertwined to such a degree that it is difficult to distinguish cause and effect, but the static, or even degenerate, condition of democracy in recent times inevitably raises the question whether it is not the result of a static economic methodology. What we observe in democratic governments is a massive and static bureaucracy aiming to keep thingsas they are, and a legislative and administrative system, hampered by checks and balances, designed to prevent change. The result is a form of government, so unfitted to deal with the conditions of change which now confront us, that we are tempted to discard it in favor of dictatorship with all the evils which that implies. If our mental attitude were altered so as to place due emphasis on change, we might look more hopefully on the future of democratic institutions.

Henry Adams predicted in his "Education" that if the rate of acceleration witnessed in recent times continued for another generation (that is, until about 1930) we should need a new social mind. He was right; we need it now, and need it badly. Has not Professor Ames shown some of it?

The striking thing about his work is that none of his ideas appear to be new. He has taken the old bricks burned in the fire of experience and made a new building out of them. This gives his building great strength because we know that the bricks are sound. The thing he has given us is a sketch of an economic philosophy, which if carefully studied by competent men, might furnish the basis for a successful national policy.

6 "Religion and the Rise of Capitalism," Tawney.

8 "The Function of Reason," Professor A. N. Whitehead, Princeton University Press, 1929, pp. 59-60. 7 Op. cit., p. 8. "Op. cit., pp. 13-15.

9 Op. cit., pp. 34-35. 10 Op. cit., p. 13.

11 For the meaning of this term see p. 5

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleProgress and Prosperity: A Suggested Program

January 1932 By Adelbert Ames, Jr -

Article

ArticleProgress and Prosperity: A Suggested Program

January 1932 By Adelbert Ames, Jr -

Article

ArticleCommentary: Cabot on Ames

January 1932 By Philip Cabot -

Sports

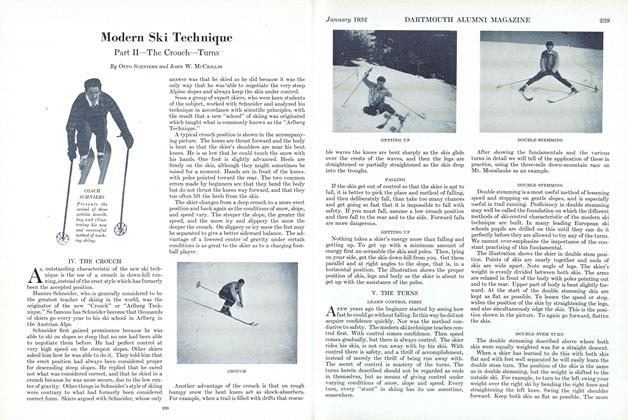

SportsModern Ski Technique

January 1932 By Otto Schniebs, John W. McCrillis -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

January 1932 By J. Branton Wallace -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

January 1932 By Arthur E. McClary

Article

-

Article

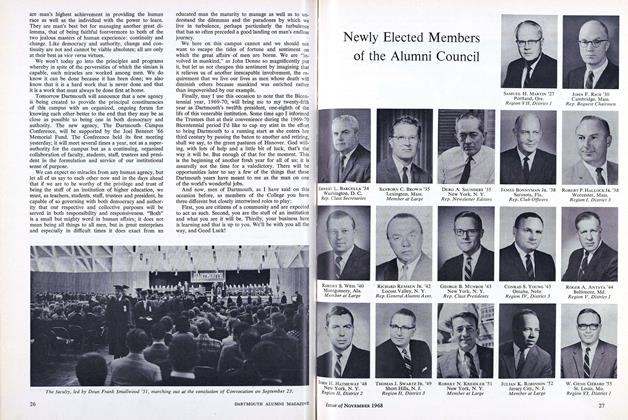

ArticleNewly Elected Members of the Alumni Council

November 1968 -

Article

ArticleClass President of the Year

JUNE 1971 -

Article

ArticleModern Corporation

APRIL 1994 -

Article

ArticleMaking Ends Meet

November 1947 By DANIEL MARX JR. '29 -

Article

ArticleA Solution to Our Woes

JAN./FEB. 1978 By GREGORY W. AUDETTE '67 -

Article

ArticleTo David McLaughlin

OCTOBER • 1987 By Harold C. Ripley '29