FOOTBALL, LIKE MOST physical games is fundamentally simple, but unlike the vast majority of games it becomes increasingly complex as men learn to play it more skillfully. When the sport originated in the latter part of the 19th century, it was largely a pastime wherein brute strength was at a premium. The team which possessed the greatest collective force in the sense of muscular power was quite certain of victory. It simply shoved or butted its opponent out of the way, or crushed it into submission, and carried the ball across the goal line.

Under such a style of play, a small, light team was at a pathetic disadvantage. It was only natural then, that teams soon devised methods of overcoming the handicaps of nature. Players realized the value of the element of surprise in launching an attack, either individually or as a unit, and the game at once became doubly fascinating.

By taking an opponent by surprise, a team potentially weaker is able to gain yardage, make touchdowns and win games. Withdraw the element of surprise, and you rob football of much of its strategy, and much of its interest.

Harvard-Dartmouth Game, 1924

EDDIE DOOLEY SAVES GAME FOR DARTMOUTH, BREAKING THROUGH SCREEN OF HARVARD INTERFERERS TO

BRING DOWN HAMMOND. DARTMOUTH 6, HARVARD O.

Harvard-Dartmouth Game, 1924

EDDIE DOOLEY SAVES GAME FOR DARTMOUTH, BREAKING THROUGH SCREEN OF HARVARD INTERFERERS TO

BRING DOWN HAMMOND. DARTMOUTH 6, HARVARD O.

With the increased interest in football which has manifested itself in recent years, play became more scientific. Many young men who had played football under the tutelage of Knute Rockne went into the coaching profession. Through the South, the Middle West, and along the Pacific Coast they spread, carrying his principles of instruction to their charges.

At the same time, other young men, who had learned their football under Glenn S. "Pop" Warner were going out into the world to teach football to various college squads. The astounding success enjoyed by their preceptors, Rockne and Warner, gave these men something of a-head start on their contemporaries who had learned their football under men less prominent in the gridiron world.

Almost unconsciously two distinct schools of football gradually developed. Gridiron enthusiasts, motivated by the labelling urge, called one system after Rockne, the other after Warner. Fortunately there were some marks of differentiation between the two systems. Warner sometimes used a double wing back formation, while Rockne favored the single wing back style of attack. But apart from the position of the backs, there is little to choose from between the two. One is no better than the other. Both are entirely dependent for their success on the manner in which the team functions.

The double wing back, or Warner system, with the halfbacks standing behind their wingmen on offense, the quarterback behind the right guard at a distance approximately two yards behind the line of scrimmage, and the fullback behind the left guard, at a distance of about four yards from the line of scrimmage, undoubtedly does allow for more trick plays, hidden ball manoeuvers, and confusing criss-crosses, than does the Rockne system.

Although only the quarterback and the fullback are in a position to receive the ball directly on a pass from the center, the wing backs are in an ideal position to cross behind the line of scrimmage, take the ball from the pilot or fullback, and swing around the end, off the tackle, or inside the tackle.

Surprise is the very keynote of the double-wing attack, for the opposition never knows just where the axe will fall. The wing backs focus attention on themselves by their work behind their own line, and just at the moment when you are certain that one of them is racing around the end with the ball, you find that the fullback has the pigskin in his possession, and is well on his way to a ten-yard gain.

One of the most important features of the Warner system lies in the fact that with a back playing close to his own wingman on each side of the line, the opposition must cover four men on forward passes, and in addition, keep a weather eye out for the other back. Then too, Warner has a habit of utilizing his linemen nicely on many of his plays, by using them as interferers; and not infrequently, when a lineman comes out to interfere, the play will go right through the gap he left in the line.

The double-wing style of attack is more fascinating I believe, than is the single wing or Rockne system, because it allows for much more handling of the ball behind the line of scrimmage, and for what might best be termed football prestidigitation and legerdermain. Of course the efficacy of the system is entirely dependent on the players and the team. A team that has plenty of man power, and is well drilled in the rudiments of successful play, can go a long way using the double wing plan of attack. That was demonstrated when Stanford clicked so splendidly in the Harvard stadium last fall.

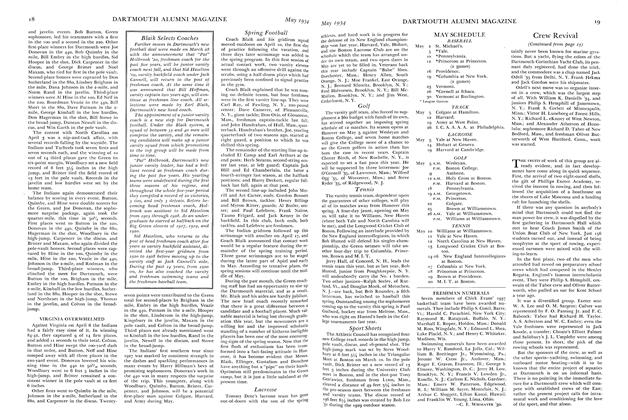

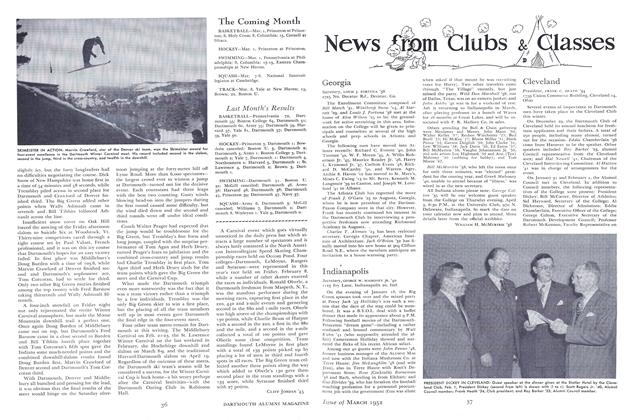

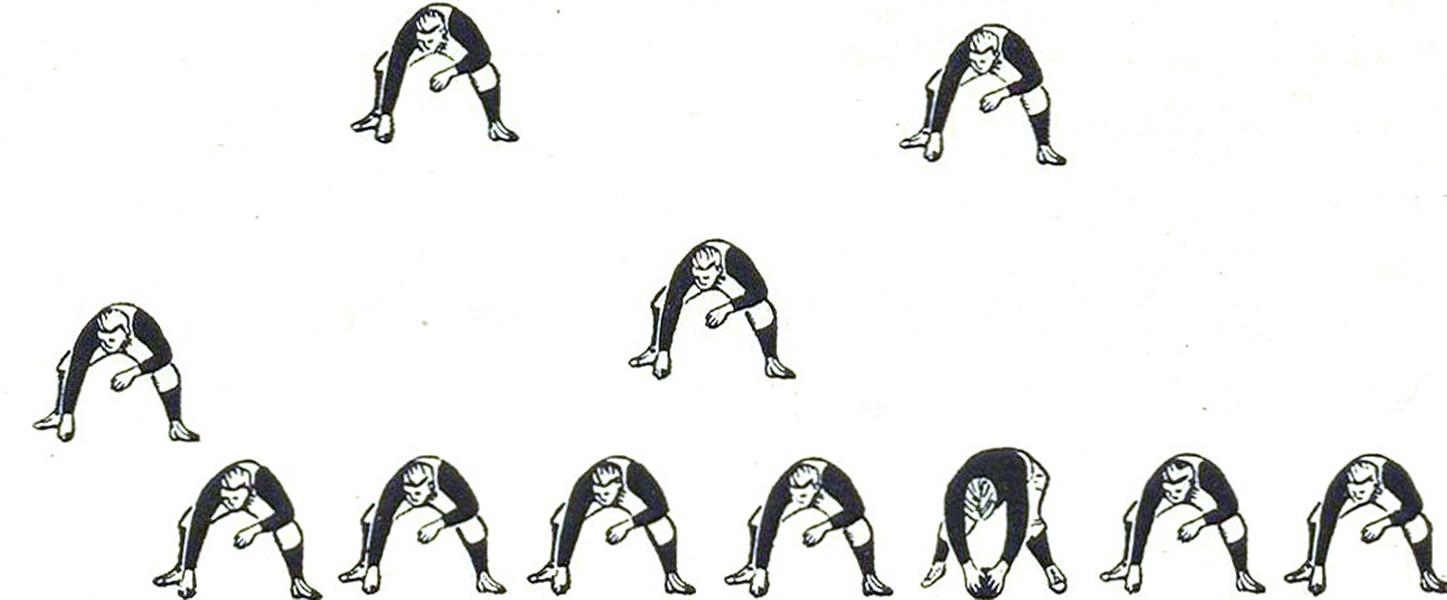

Double Wing Back Formation—Warner.

Double Wing Back Formation—Warner.

The Rockne system, or single wing back style of offense, was in vogue long before the great gridiron teacher of South Bend first turned his mind to the development of teams. There is even some doubt today whether the Warner system was invented by the old sage of Carlisle. Regardless of whom it was who first used these formations, the fact remains that Warner and Rockne were their most successful exponents.

The Rockne plan of attack calls for one wing back who plays behind or outside the end, the quarterback close behind the line, stradling the guard and tackle, the halfback back about three and a half to four yards, and to the right of the quarterback, and the fullback about the same distance from the line, and a little to the right of the center. Of course there are all kinds of variations to the single wing form of offense, but the box formation employed by Notre Dame is a pattern widely followed.

Rockne, like Warner, used an unbalanced line, and although his backs appeared bunched together, they were able to strike with terrific force on either side of the center. I recall how, in the Army-Notre Dame game at Chicago two yeras ago, the South Bend backs would shift to the right, only to smash through the weak side of their own line, and catch the Cadets off guard repeatedly.

With the massing of strength on one side, the opposition must shift to meet the blow. The moment the defending line shifts, it makes itself vulnerable to an attack from the weak side. Perhaps an even more important point in favor of the Rockne plan of attack is in having three backs ahead of the ball carrier the moment the ball is snapped.

There is really nothing inherently mysterious or formidable about either plan of attack. Each of them has its virtues. The success of any style of play is dependent on the players who make up the team. Rockne and Warner both coached men to interfere effectively, to block precisely, and to use power with deception; in other words, to surprise the opposition.

Rockne, as a matter of fact, never thought very highly of the double-wing back style of attack. I remember talking "systems" with him, at the Astor Hotel, the night of the testimonial dinner to Frank Carideo. He said the double-wing formation could be crippled quickly and quite permanently by sending the defending ends into the offending team's backfield to "take-out" the wing backs. Once they are on the ground, it is a comparatively easy matter to stop the ball carrier.

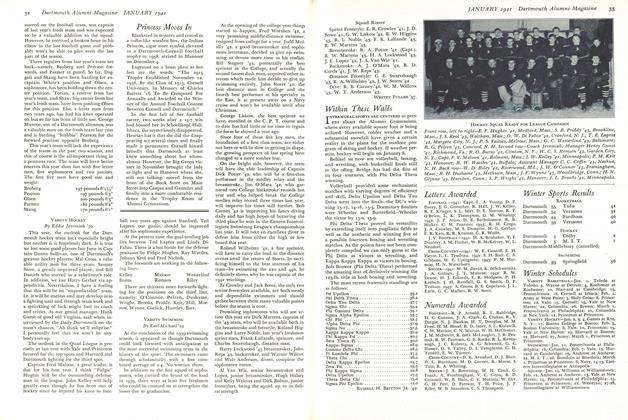

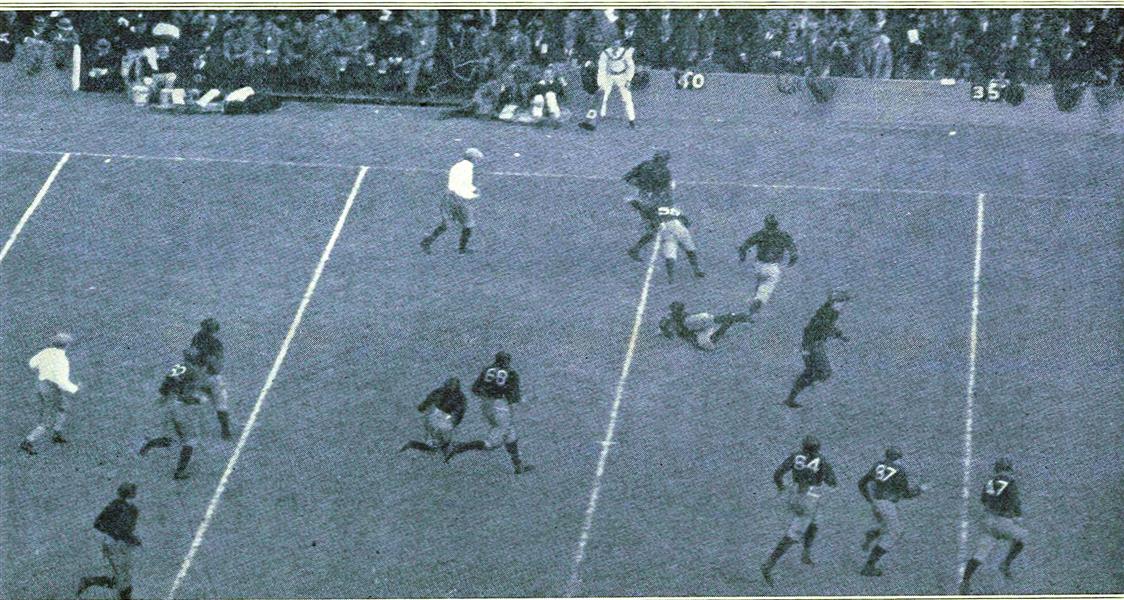

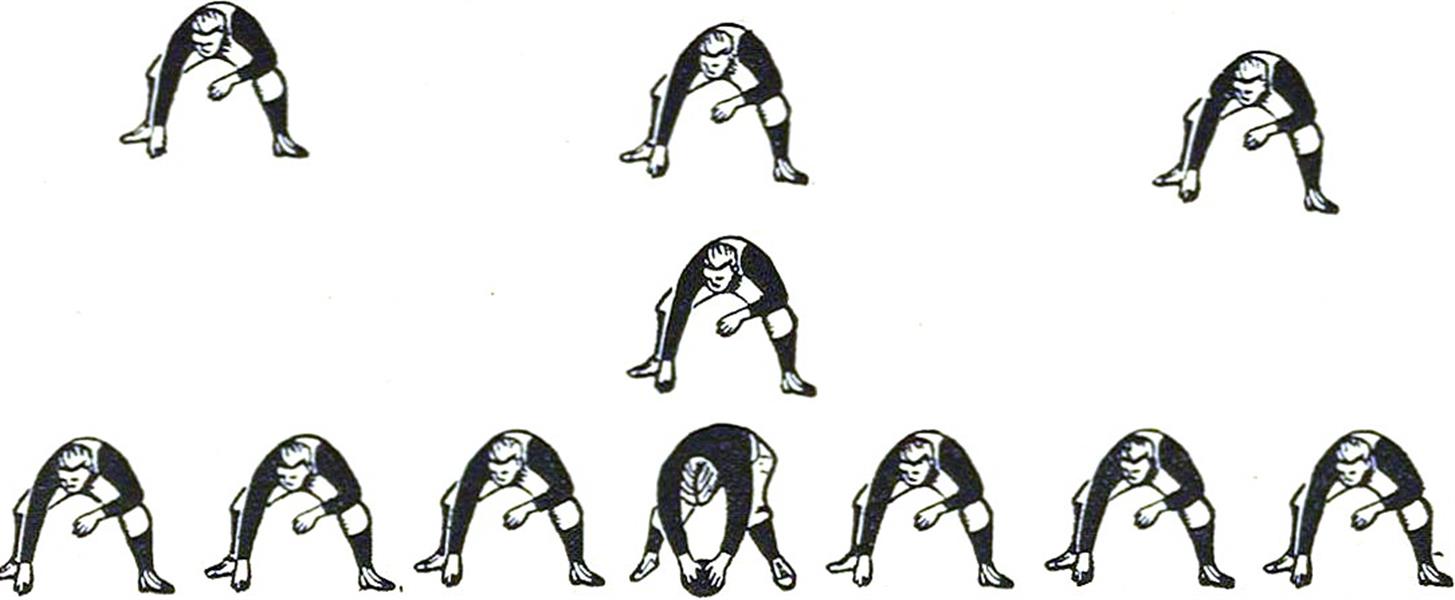

Single Wing Back Formation—Rockne

Single Wing Back Formation—Rockne

"But how," I asked him, do you protect your ends from sweeping runs, after you have sent your own flank men crashing into the enemy's backfield?" The dynamic "Bald Eagle" of the cross-barred field chuckled merrily, and for a moment I was sure he forgot the thrombosis which at that time was bothering him.

"By the simple expedient" he replied, "of using floating tackles. I simply tell my tackle to drift out laterally the moment the ends charge in, and in that way my tackles cover the territory which rightfully should be taken care of by our ends." Rockne went on to tell how effective his system had proven against the Warner style of attack, and his enthusiasm for it convinced me that it must have been unusually efficacious.

Besides the Warner and Rockne systems, which I have outlined, there are only two other basic styles of attack on which offensive formations may be fashioned. Rockne and Warner of course had their pet ideas as to the manner of charging linemen out of position, and of playing defensively on the forward wall. It would not do however to enter into an explanation of the fine points of their line technic, as space would not allow a thorough treatment of the subject.

The other two formations mentioned above are the simple T formation, which has at times proven very effective; and the kick formation. These, along with the Warner and Rockne backfield formations, comprise the complete category of backfield systems, if such they may be called. All other formations are simply slight modifications of one or another of these.

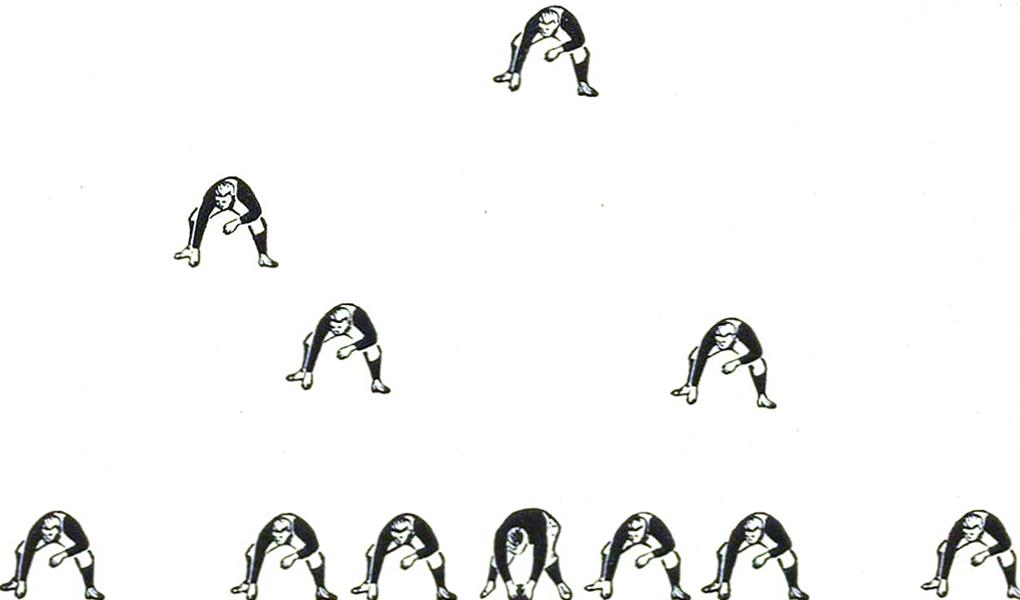

Simple T Formation

Simple T Formation

II

TIME AND A&AIN most of us have heard the phrase—"a strong offense is the best defense." Some writers have stated that in these words Dartmouth's football policy could be summed up. Nothing could be more erroneous. Dartmouth teams have never neglected defensive football. Catchy phrases like that are often misleading. A strong offense is really no defense at all, unless one is to assume that the opposing team will never have possession of the ball.

An entirely different technic is required for defensive football from that of offensive football. If a team is to be well rounded, and successful, it must be instructed in both. Football is more than a mere scoring bee. And if a team hopes to cope triumphantly with its rivals it must know as much about defensive football as offensive football.

The most successful coaches around the Metropolis, and I mention them merely because I have had a better opportunity to study their methods than those of other coaches, stress defensive football more than offensive football. Lu Little who has lifted Columbia out of the gridiron "doldrums," and transformed it into one of the leading eastern teams, emphasizes defense constantly.

Coach Little employs a very close line both defensively and offensively, and, unlike many coaches, he instructs his forwards to forget the ball carrier and cover territory. Only when the man who is carrying the ball runs directly into the arms of a Columbia lineman will the latter tackle him. Little believes that the tackling should be done by the backs. These men are taught to come up fast, and bring down the runner. The idea works out very well, for very few touchdowns have been scored against the Lion team in recent years.

Major Frank Cavanaugh, coach of Fordham, has enjoyed tremendous success in recent years, and like Little, he stresses defensive play in preference to offensive play. Over a period of three seasons, I am fairly sure, Fordham has had less points scored against it than any other team in these parts. Its policy seems to be, "don't let the other team score, and when it weakens, score a touchdown or two yourself."

I do not want to create the impression that either of these mentors neglect the attacking phase of football. They don't. But if the scales tip at all, and they doubtless do, they reveal an emphasis on defensive rather than offensive football.

III

ANY SPORT IN WHICH bodily contact plays a vital part is bound to be rough and dangerous. In football, where bodily contact takes place on every play, and is the climax of every sequence of gestures, the danger of serious injury is forever present. That fact was conclusively demonstrated last fall in the tragic catastrophies which befell so many football players. Injuries and fatalities cast a pall over the season of 1931.

The football rules committee, the controlling body of the game, acted with commendable foresight when it endeavored to eliminate the "deathtraps" in the game, by passing six new rules which are in effect this season. Although at first there was considerable opposition from the coaches who feared that some of their pet theories would be shattered by the prohibiting influence of the new mandates, they have been convinced, with but few exceptions, of the tremendous value of the new rules in safeguarding the lives of the players, and in humanizing the play along the forward wall.

Anyone who has played football knows that many linemen playing on the defense were not reluctant to perpetrate brutalities on their adversaries. Instead of pushing an opponent out of the way, they jolted him out of the way with the heel of their hand. All the punishing play of the line passed out the football portal when the new rules came in; and so did the flying tackle and the flying block, thrilling but inherently dangerous plays that they were.

The flying tackle was one of the most spectacular plays in football. Watching a player hurl himself through the air at the churning legs of a ball carrier seemed to epitomize all the heroic qualities of the sport. And yet, a flying tackle, apart from being foolhardy, was never as effective as a charging tackle in which a man keeps his feet on the ground and hurls his opponent to earth with considerable force.

In interpreting the new rules, the officials have agreed that a man's feet may leave the ground in tackling or blocking, provided he is within arms' reach of the runner. Experience has shown that this is the most feasible interpretation of the revised code.

Other rule changes effect substitutions, the kickoff, and equipment. By permitting a man withdrawn from the game in one period to return in any subsequent period, the rules committee has struck a powerful blow at the cause of many injuries. William Crowley, a well-known football official, told me after the Dartmouth-Yale game last fall, that time and again he had seen players virtually out on their feet pretend that they were able to carry on, in order that they would not be taken out of the game in the second half. They knew that once removed they couldn't return, and they either felt their team needed them badly, and were indispensable, or they were gourmets for punishment.

At such times, when players are groggy from a blow, or in need of medical attention, they subject themselves unnecessarily to serious injury. Their reflexes are slowed down, and they are targets for the opposition. Fortunately the new rules make this unofficial procedure on the part of the players absolutely unnecessary. This year, and henceforward, a man taken out in one period may return in any subsequent period.

The kickoff rule of 1932 not only gives the kicking team the option of place kicking or dropkicking the ball to its opponent, but it requires that five men of the receiving team remain within five yards of their own restraining line. In other words, when the kickoff is made from the regular position, that is, on the 40-yard line, the receiving team must have five men stationed within fifteen yards of the line whereon the ball is resting. The restraining line of the receiving team is ten yards from the ball, i.e. the 50-yard line. And the five men must be within five yards of this stripe, namely on their 45-yard line. This provision curtails the use of the flying wedge. With five men on the receiving team up front on their own forty-five yard line, only six men are left to cover the remaining area. And by the time the five front men can form into a wedge, the players of the kicking team can get down to the receiver, thus making the wedge useless.

Kick Formation

Kick Formation

The equipment rule is an intelligent bit of legislation. In recent years, manufacturers of football equipment have fashioned knee pads, elbow pads, and thigh guards out of unyielding fibre which while admirably protective were at the same time very dangerous. The new rules require such equipment to be padded on the outside with a layer of rubber or other soft substance.

The "dead ball" rule, which holds that the ball is to be considered dead the moment any part of the ball carrier's body, except his hands or feet, touches the ground, is another extremely valuable bit of law making. In other years, when a player fell to the ground, either on a line plunge, or a wide sweeping play, he was pounced on by his opponents who came at him from all sides. They wanted to be certain that he would not get up and go on. All that is unnecessary now. The ball is automatically declared dead when his body, or any part of it except his feet or hands touches the ground. If a man is out in the clear, and on his'way to a touchdown, the ball will nevertheless be declared dead, should he slip and fall. This seems a bit harsh, but the rules committee and the officials agree (and the coaches will very shortly) that for the sake of protecting the players the rule must hold under all circumstances.

People sometimes wonder what happens in the huddle. The answer is, virtually anything. Originally the huddle was simply a device invented out of necessity. Teams couldn't hear their quarterbacks barking the signals. The roar of the crowd drowned out the pilot's voice. By gathering the team around him, he could impart the signal for the next play, without straining his vocal organs.

In recent years, coaches like Chick Meehan, Lou Little, Dick Hanley, and Fritz Crisler have employed the huddle as a psychological weapon. By instructing their teams to come out of the huddle in a complicated and confusing fashion, they feel they can bewilder the opposition, and thus make it vulnerable to a sudden attack. In other words, a tricky huddle enhances the element of surprise.

I think one of the best answers to the question— "what takes place in the huddle?" is found in the story of the little Midwestern team that was losing to Michigan by the score of 86 to 0. Towards the end of the last period, when the losing team was weary of the fray, Michigan's halfback fumbled the ball, and the little team found itself in a scoring position on Michigan's 8 yard line.

The members of the little team were so astounded at the turn of events that they didn't know what to make of it. The quarterback finally called the team back in a huddle. "Fellows," he said, "this is our one glorious opportunity. Here we are on Michigan's 8-yard line. I must confess though, I am a little at a loss as to what to do."

Right then and there a third string substitute end spoke up and said: "I have an idea. I think we ought to try a long incompleted forward pass." And they did.

IV

THE CURRENT SEASON is well along now. As in other recent seasons, the number of small teams that have defeated big and prominent adversaries has been noticeable. Young men all over the country are physically of about the same potentialities. And with the spread of expert coaches through the land, the calibre of play of smaller teams is bound to improve. That it has improved has been demonstrated repeatedly.

Another admirable feature of modern football is the fine spirit in which it is played. The bitter antipathies of two decades ago have been supplanted by an attitude of genuine amicability and sportsmanship. The players themselves look upon football as a game, a game that should be enjoyed, and in doing so they do not forget for a moment the cherished traditions of their respective alma maters, which motivate them on the field of play.

The game today is played just as hard as it was in the days of "Squash" Little, Hefflefinger, Hardwick, and Hare. It is a thrilling and delightful Spartan pastime. The new rules have not deprived it of any of its natural ruggedness. And it is still the sport of sports.

Photo captions

Harvard-Dartmouth Game, 1924 EDDIE DOOLEY SAVES GAME FOR DARTMOUTH, BREAKING THROUGH SCREEN OF HARVARD INTERFERERS TO BRING DOWN HAMMOND. DARTMOUTH 6, HARVARD O.

Double Wing Back Formation—Warner.

Single Wing Back Formation—Rockne

Simple T Formation

Kick Formation

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE PERSONALITY OF WEBSTER

November 1932 By Claude M. Fuess -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

November 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleEditorial Comment on the Opening Address

November 1932 -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1936

November 1932 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

November 1932 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

November 1932 By C. E. Leech