"THE NUMBER of those in this country who have had benefit of formal education, supplemented by the host of those who without such advantage have like high intelligence and good will, is sufficiently great to assert itself effectively in the creation of a new spirit towards government and in the establishment of a new social order. If the cult of the commonplace and the vogue of the average thrust aside or submerge the ideals and aspirations cherished by individuals, as for instance in the case of many a man on graduation from college, what reason exists why there should not be a mobilization of such men for cooperative action? Is the proosal as quixotic as it may sound? Is education impotent to help in salvaging civilization? Are the educated classes, as Gerald Stanley Lee suggests, incapable of any fine frenzy for the establishment of their ideals and are they simply what he calls 'yearners'? I think not."

As one of the concluding paragraphs of President Hopkins' address at the opening of College, an address which has come to be eagerly awaited by editors and influential citizens throughout the nation, these questions are flung as a challenge to those who are at all concerned with current and future events. Coming at a time when the "educated classes" are yearning for a governmental leadership that would inspire enthusiastic support in raising ideals and intelligence in Washington to a new level, the address climaxes a series of remarkable statements by the President and presages more to come.

Years ago, soon after the war, his protests against the methods utilized in raids upon aliens marked for deportation, though questioned at the time, were later substantiated both by decisions of the United States Courts and by public opinion. Later, his denunciation of "Fundamentalist" efforts to dictate what could be taught in American colleges antedated any public knowledge of the resources and aggressiveness of this movement.

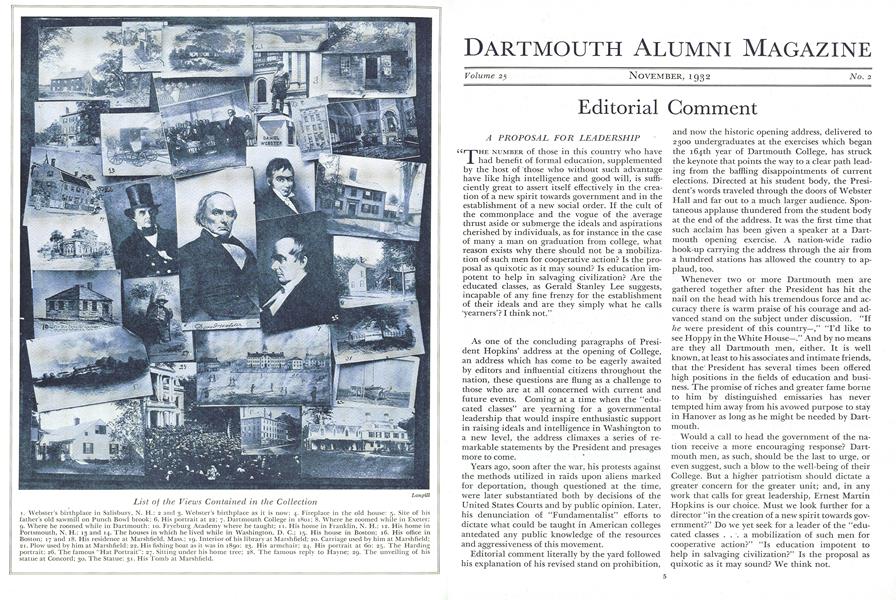

Editorial comment literally by the yard followed his explanation of his revised stand on prohibition, and now the historic opening address, delivered to 2300 undergraduates at the exercises which began the 164th year of Dartmouth College, has struck the keynote that points the way to a clear path leading from the baffling disappointments of current elections. Directed at his student body, the President's words traveled through the doors of Webster Hall and far out to a much larger audience. Spontaneous applause thundered from the student body at the end of the address. It was the first time that such acclaim has been given a speaker at a Dartmouth opening exercise. A nation-wide radio hook-up carrying the address through the air from a hundred stations has allowed the country to applaud, too.

Whenever two or more Dartmouth men are gathered together after the President has hit the nail on the head with his tremendous force and accuracy there is warm praise of his courage and advanced stand on the subject under discussion. "If he were president of this country—," "I'd like to see Hoppy in the White House—." And by no means are they all Dartmouth men, either. It is well known, at least to his associates and intimate friends, that the' President has several times been offered high positions in the fields of education and business. The promise of riches and greater fame borne to him by distinguished emissaries has never tempted him away from his avowed purpose to stay in Hanover as long as he might be needed by Dartmouth.

Would a call to head the government of the nation receive a more encouraging response? Dartmouth men, as such, should be the last to urge, or even suggest, such a blow to the well-being of their College. But a higher patriotism should dictate a greater concern for the greater unit; and, in any work that calls for great leadership, Ernest Martin Hopkins is our choice. Must we look further for a director "in the creation of a new spirit towards government?" Do we yet seek for a leader of the "educated classes ... a mobilization of such men for cooperative action?" "Is education impotent to help in salvaging civilization?" Is the proposal as quixotic as it may sound? We think not.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE PERSONALITY OF WEBSTER

November 1932 By Claude M. Fuess -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

November 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Sports

SportsTHIS GAME OF FOOTBALL

November 1932 By Edwin B. Dooley -

Article

ArticleEditorial Comment on the Opening Address

November 1932 -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1936

November 1932 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

November 1932 By Albert I. Dickerson

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

January 1950 -

Article

ArticleThe color lithograph shown

JANUARY 1969 -

Article

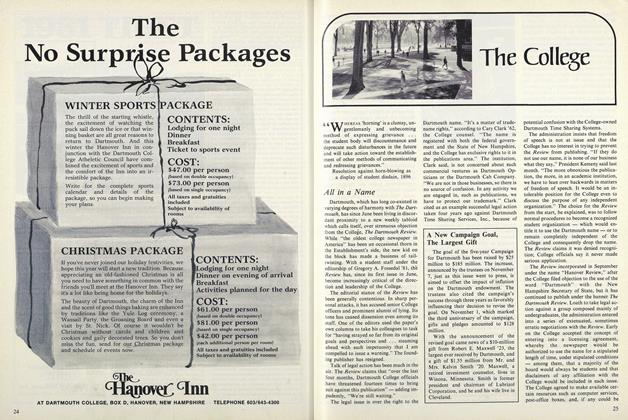

ArticleAll in a Name

November 1980 -

Article

Article1901

May 1939 By EVERETT M. STEVENS -

Article

ArticleSome Memorable Teachers

MAY 1930 By Professor E. J. Bartlett -

Article

ArticleDR. J. W. BARSTOW '46 ONE OF OLDEST COLLEGE MEN

November, 1922 By W. W. Eggleston '91