ICQ OMETHING THERE is that doesn't love a 13 wall, that wants it down," wrote Robert Frost. And it may be that future generations will twist the meaning of these words, and accept them as the keenest architectural prophecy of an age in which the major certainty was change. It has been a mark of the careless exhuberance of our time to fling up soaring buildings of steel, and then within fifteen or twenty years to pull them down to make way for new towers bigger and, happily, generally better. Steel, as a stuff for making walls, has melted away before the restless heat of social change faster even than adobe bricks under tropical rains.

Painting pictures upon walls surely ranks among the most ancient as well as the most persistent and universal forms of, artistic expression. And yet it is hard to see how a tradition of genuinely great mural painting can be maintained when the surfaces to be painted promise to have such a fragilely ephemeral life as have modern walls of steel.

The New England college is often, and perhaps justly, criticized because of its isolation from the swift current that flows through the metropolitan centers of modern life. But there are many who find advantages in the fact that it is so isolated, and among the advantages may be listed what seems to be a fair assumption—that the buildings of a college like Dartmouth have as good a chance of surviving the next hundred years as any in the country.

It is, then, both fitting and full of exciting promise that Dartmouth College should be offering the hospitality of certain of its walls to the sure and luminous art of Jose Clemente Orozco.

No one who has noted the hum of activity that centers in Carpenter Hall—in its classrooms, its galleries, and its studio where dozens of students are painting vigorously and enthusiastically with the helpful encouragement of Mr. CarlosSan Sanchez—can doubt that Dartmouth is interested in painting. To one observer, at least, this interest appears to be spontaneous and keen, unmannered and vigorous, and altogether as healthful as anything that is happening in this community.

It would be hard to imagine anything that would feed and stimulate this interest in painting more than the opportunity which now is offered of watching Mr. Orozco paint his frescos. To look at and to appreciate a finished painting is to apprehend to some extent the conception which stirred the artist's emotion. But to watch him at his work is to share some part of the tense excitement of the creation itself. If there is any merit in the contention that the most effective education comes by contagion, in the contact between an interested student and a teacher who is a master of his craft and who is himself at work, the present project promises to turn into one of the most hopeful educational experiments ever attempted in an American college.

It has added merit in that it will leave something of permanent worth for college generations that will follow the present one. If the assumption be accepted that the walls of Dartmouth College are as likely to survive as any in the country, it is hard to keep one's imagination from interpreting the present program as the first step in a large and very fascinating project. One of the things that makes Dartmouth College a most interesting place in which to work is that it is a going concern—organic and alive. The art of mural painting, too, is organic and alive. Surely, a strong case may be made for a continuing alliance between the two institutions.

The claims that Dartmouth may make upon the time and genius of Orozco necessarily are limited. But after he has finished his work here, Dartmouth College still will have walls that would be the better for decoration by great painters, and there will be new generations of students and new faculty members who will have equal enthusiasm for watching excellent mural work in progress. If, at intervals over the next hundred years, Dartmouth were to invite mural painters who represented the finest traditions of their craft, to work upon the walls of present or future Dartmouth buildings, at the end of such a period the College would have something that was not alone unique but very satisfying. In addition, it would have provided much of the healthiest sort of education, and would have contributed one of the most useful and respectful services that may be paid to art, in the appreciation and employment of its contemporary masters.

If it is permissible even to speculate upon the possibility of so broad a project, the selection of Jose Clemente Orozco to do the first Dartmouth frescos is unquestionably a happy one. The fact that one man of acknowledged greatness has consented to work at Dartmouth should makeit easier for the College to claim the services of other painters of first rank in the future, if that should seem desirable. In any event, there is a fine if bold fitness in the wedding of Orozco's painting to Dartmouth buildings, which in the simplicity of their lines, the fineness of their proportions, and the clean modernity of their interiors are peculiarly adaptable to mural decoration. Orozco's work has many of the qualities that we like to associate with the College. It is completely masculine. It is forthright and unmannered and contemporary. It is democratic and deeply concerned with social values, ft would be ridiculous, certainly, for us to claim kinship with this Mexican painter in a parochial sense, but to the larger plane of American life Orozco is as autochthonous as New Hampshire granite, or the Mississippi River, or Samson Occom himself. To the latter worthy the art of Jose Clemente Orozco would have been far more intelligible than any of the works that have come out of Concord.

It is important, too, that Orozco's painting is sufficiently abstract and sufficiently universal in theme to give promise of wearing well over the years to come. It is, no doubt, true that no one can predict with certainty what our great grandchildren will judge to the fine. But if the people in colleges have not the courage to stake their judgments upon the matter, who in contemporary life will? The work of Jose Clemente Orozco has as good a chance of weathering the judgment of time as that of any living mural painter.

We can be surer of contemporary judgments. When Robert Frost wrote "Something there is that doesn't love a wall, that wants it down," he was not thinking of walls mended by an Orozco. It is possible though thathere lies the clue to the inner meaning of that terse remark of this New England farmer, "Good fences make good neighbours." If our fences, or walls, can be made "good," Orozco is a man who can make them so. And many of us will have the sense of contributing something to a great group project, even though we only stand and wait and look. It is difficult to see how we can help but be the better for it.

Jose Clemente Orozco

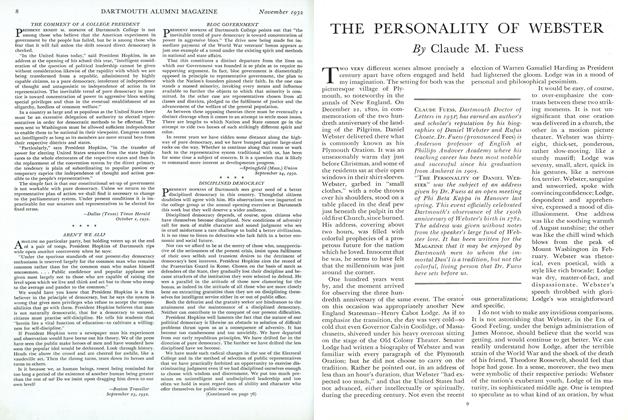

"Release" Orozco's introductory fresco at Dartmouth, completed in May, at the end of the corridor connecting Carpenter Hall with Baker Library

Prometheus THE FAMOUS OROZCO MURAL IN TRUE FRESCO AT POMONA COLLEGE, CLAREMONT, CALIFORNIA

JOSE CLEMENTE OROZCO, the Mexicanfresco artist, came to Hanover last Mayon appointment of the College to exhibit the methods of painting fresco. Duringhis stay here, in which he completed thefresco "Release" at the end of the corridorconnecting Carpenter Hall with the library,he became interested in the walls of thereserve book room of the library, comprising more than 3,000 square feet of spacein ideal proportions, as a place for the vastproject which had been developing in hismind for some time, depicting the epic ofcivilization on the American continent. Itwas later announced that he would be continued in the capacity of a visiting memberof the department of Art and would returnsoon to begin work on the largest frescoyet produced in the United States. Orozcobegan work in June on the great muralseries, built around the myth of Quetzalcoatl, the messiah of the Americas. He hasreturned to Hanover this fall after a summer in Europe to continue his work.THE ACCOMPANYING article by Stacy May,who resigned his Dartmouth professorshipin June to accept a position with theRockefeller Foundation, greeted Orozco'sfirst appointment at Dartmouth with pleasure and expressed a hope that it might bethe beginning of a tradition that woulddecorate Dartmouth walls year by yearwith the murals of great contemporaryartists in this most permanent of forms.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE PERSONALITY OF WEBSTER

November 1932 By Claude M. Fuess -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

November 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Sports

SportsTHIS GAME OF FOOTBALL

November 1932 By Edwin B. Dooley -

Article

ArticleEditorial Comment on the Opening Address

November 1932 -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1936

November 1932 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

November 1932 By Albert I. Dickerson

Article

-

Article

ArticleR. R. MARSDEN, 1908 APPOINTED PROFESSOR IN THAYER SCHOOL

July 1919 -

Article

ArticleBASKETBALL

January 1920 -

Article

ArticleFEW FAILURES ANNOUNCED AFTER MID-YEAR EXAM

March, 1924 -

Article

ArticleResults to Date

January 1952 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Article

ArticleTOPLIFF HALL

March 1944 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleYankee Editor

MARCH 1972 By MARY ROSS