By Lewis Mum- ford. Harcourt, Brace, 1931. 266 pp.

This book should make a double appeal to the interest of the Dartmouth constituency. It gives in permanent form the essence of the Guernsey Center Moore Foundation lectures delivered in Hanover in December, 1931. Moreover the author is still connected with the College, albeit only in an occasional capacity. Five times during the present academic year Mr. Mumford is scheduled to be in Hanover for a week at a time to consult with students, give informal talks, and in other ways impart a stimulating influence. The marked success of this new, intellectual sort of extra-curricular activity makes it desirable' that the experiment should be better known. It is one which deserves repetition and extension.

The period surveyed in the book is that of the generation following the Civil War. It has received various opprobrious names— The Gilded Age, The Tragic Era, The Dreadful Decades. Mr. Mumford calls these thirty years "The Brown Decades." It was as though the age took its hue from adaptation to the visible smut of industrialism. "By the time the Civil War was over, browns had spread everywhere: mediocre drabs, dingy chocolate browns, sooty browns that merged into black. Autumn had come. The whole country looked darker, sadder, soberer."

But it was not to repeat the disparagement of those outwardly unlovely years that Mr. Mumford wrote his book. Rather it was for the purpose of discovering the usable past, of unearthing our buried Renaissance; for, as Rodin pointed out, "America has had a Renaissance, but America doesn't know it." Passing in review all the arts, save only music, our author is convinced that the years in question were "especially in architecture, engineering, landscape design, and painting, a formative period of American culture, comparable to the Golden Day in literature." The Golden Day, be it said, is the age of our literary florescence before the Civil War—a period about which Mr. Mumford had already written one of his best books.

Literature is touched upon but lightly in this volume. Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson receive their passing meed of praise. But it is plainly the renewal of the landscape and the renovation of architecture which engage Mr. Mumford's chief interest. These were the years when our city parks were laid out and the beginning was thereby made of our modern city planning. Our great national parks were also set apart from exploitation and violation. By the end of the period, which coincides with the passing of the frontier, a wholly new attitude toward this important matter had been engendered.

Mr. Mumford regards architecture as the most social of the arts and in consequence looks upon individuality or personality in it as a mark of disintegration. He believes that the years 1880 to 1895 were the turning point for us in architecture. Such leadership as America now possesses in this art may be largely traced back to Henry Hobson Richardson who made possible the later original work of men like John W. Root, Louis Sullivan, and Mr. Frank Lloyd Wright.

American painting likewise arose for the first time in the nineteenth century to the level of our literature. The highest place is reserved for Albert P. Ryder, who, it is interesting to note in passing, was also accorded a special chapter in Mr. Thomas Craven's recent book "Men of Art." Thomas Eakins, Winslow Homer, John LaFarge and others receive discriminating praise. But, in general Mr. Mumford is fairly ruthless in dealing with "established" reputations. Whistler is dismissed with only a brief mention, as if he had forfeited further consideration by removing himself from the American scene. Sargent is accused of essential emptiness of mind. The much-vaunted tower skyscrapers of recent years are described as "grandiose and inefficient."

The author's main contention, that there is much in those generally decried years that is formative and significant for us, is amply vindicated. The reader of this skilfully argued and happily phrased book will never again be able to think of those three decades as unreservedly and unrelievedly the Period of Bad Taste.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleFrom War to Depression

March 1932 By Bruce Winton Knight -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

March 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorDartmouth Manuscript Series—The First Volume

March 1932 -

Article

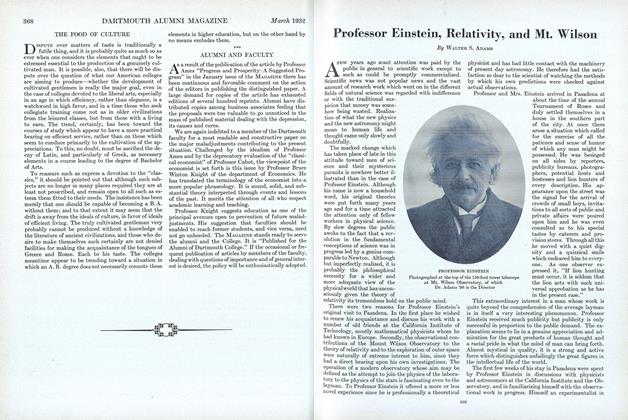

ArticleProfessor Einstein, Relativity, and Mt. Wilson

March 1932 By Walter S. Adams -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1931

March 1932 By Jack r. Warwick -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

March 1932 By Arthur E. McClary

W. K. Stewart

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

May, 1922 -

Books

BooksTHE HISTORIAN AND HISTORY.

OCTOBER 1964 By HARRY N. SCHEIBER -

Books

BooksPRIVATE WOMAN, PUBLIC STAGE: LITERARY DOMESTICITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICA

OCTOBER 1984 By HENRY TERRIE -

Books

BooksTHOMAS DE QUINCEY.

OCTOBER 1969 By JAMES A. W. HEFFERNAN -

Books

BooksOUR FLIGHT TO ADVENTURE.

January 1957 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksWITHIN THESE BORDERS.

January 1954 By JOSEPH B. FOLGER '21