By Charles A. Dinsmore '84. Houghton, Mifflin Co., Boston, 1937. p. 251. $2.75.

Mr. Dinsmore is best known in the world of scholarship as one of the leading American authorities on Dante. If my memory serves me correctly, it was he who delivered the commemorative address at Dartmouth in 1921, when our College along with the rest of the world celebrated the six hundredth anniversary of the great Florentine poet's death. The present volume has grown out of a series of lectures in the Divinity School of Yale University. It has an analytical table of contents and a useful index. I can best indicate the nature and purpose of the book by quoting from the author's Preface: "The contents of the following pages rest upon certain fundamental assumptions; that the meaning of life is of vital interest to us all; that poets are our most beloved and persuasive teachers of what makes life significant; that the poets who are truly great are those who have presented the largest area of human experience most justly and powerfully; that they have become unmortal because their ideas and ideals run accordantly with the deepest currents of our belief in the realities of life; that they teach by what they say, but more by the characters they create, the principles they take for granted, the moods they communicate."

Mr. Dinsmore has chosen Homer, Aeschylus, Lucretius, Virgil, Dante, and Shakespeare as interpreters to us, in terms of life, of what men have most valued. The inclusion of Lucretius strikes one at first as peculiar—his philosophy of naturalism seems a bleak and sweeping denial. But the author finds that Lucretius, too, lived by faith, ennobled men's thoughts, gave them courage and a wonderful vision. All six poets have certain characteristics in common, in that they were men of positive faith, who penetrated to the heart of things, saw clearly what was wrong with the world, but believed implicitly that wisdom came through suffering and that men could rise superior to misfortune. All taught that character was destiny.

The author notes that each of these poets appeared at a time when his native language was either just coming to the plenitude of its glory, or else was already in full flower. Yet Mr. Dinsmore is entirely in favor of using English translations, and sometimes prose translations at that. He reminds us that our English Bible is a translation, and devotes what is probably the most eloquent chapter in this frankly inspirational book to the Supreme Epic—the Hebrew-Christian Scriptures.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

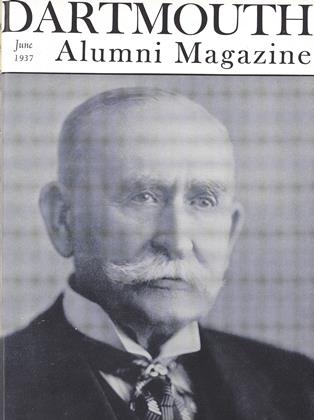

ArticleMr. Tuck 75 Years After Graduation

June 1937 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Article

ArticleCollege of a Thousand Elms

June 1937 By PROFESSOR CHARLES J. LYON -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1927

June 1937 By Doane Arnold -

Article

ArticleHow Does the College Change?

June 1937 By ROBERT DAVIS '03 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1931

June 1937 By Edward D. Gruen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1936

June 1937 By Richard F. Treadway

W. K. Stewart

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE LAST ADAM.

MAY 1967 By FRED BERTHOLD JR. '45 -

Books

BooksTHE CAUGHT IMAGE.

JULY 1964 By HENRY L. TERRIE JR. -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

January 1918 By JAMES FAIRBANKS COLBY -

Books

BooksGEOCHEMISTRY OF BERYLLIUM AND GENETIC TYPES OF BERYLLIUM DEPOSITS.

OCTOBER 1966 By JOHN B. LYONS -

Books

BooksTHE MARKET FOR COLLEGE-TRAINED MANPOWER: A STUDY IN THE ECONOMICS OF CAREER CHOICE.

JANUARY 1972 By MARTIN SEGAL -

Books

BooksAll Biology Is Indebted . . .

November 1983 By Peter Smith